Context can reduce accurate word learning

15 Replies

I’ve been reading an interesting 2017 dissertation by US researcher Reem Al Ghanem in preparation for this month’s DSF conference. It’s about how children learn to read and write polysyllabic words.

One section jumped out at me, because multi-cueing and the idea that phonics/word study should occur in context is still popular in many Australian schools:

“When poor readers rely on context to aid word recognition, they focus on selecting semantically appropriate words given the context clues rather than decoding the words through letter-sound conversion strategy.

“When children utilize a compensatory strategy like contextual guessing rather than phonological decoding to aid their word recognition, their attention to word form is limited, resulting in poorer acquisition of word-specific representations, hence the negative context effects.

“When poor readers are presented with words in isolation, they are forced to read them using phonological decoding. Although inefficient, their phonological decoding of the words increases their attention to the orthographic details of the words, resulting in acquiring higher quality representations for the words than when they are presented in

context.” (p103)

Developing high-quality word representations is a challenging activity for struggling readers. Expecting them to only learn words in context is a bit like asking them to only learn to shoot netball or basketball goals during a real game, and discouraging goal-shooting and other skills practice.

As a weedy, unco, asthmatic kid keen to avoid on-court humiliation, I voluntarily did many hours of goal-shooting practice. Imagine if coaches discouraged such practice, and said sporting skills should only be learnt in the context of real games. We’d all stare at them. Then ignore them.

Al Ghanem’s dissertation goes on:

“While context clues can support comprehension, they are unreliable sources for orthographic learning. Teachers must select the instructional strategy that fits the goal of instruction, and presenting words in isolation appears to be the most beneficial when the goal of instruction is acquiring word-specific representations.” (p107)

New year, same crappy old Education Department advice

20 Replies

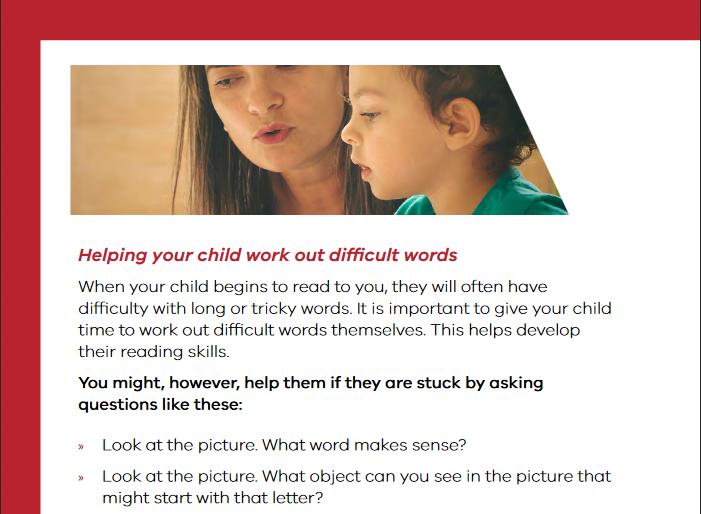

In 2018, my state’s Department of Education and Training (DET) produced a brochure for parents called “Literacy and numeracy tips to help your child every day”.

Its top recommendation for “Helping your child work out difficult words” was to tell them, “Look at the picture. What word makes sense?”

Its authors clearly weren’t across the scientific research on how the brain learns to read, which shows that strong readers read (surprise!) the written words in books. Guessing words from pictures or context is only the strategy of 1. weak readers, and 2. learners trying to read books containing spelling patterns they’ve never been taught (e.g. predictable texts, still sadly widely used in schools).

I wrote a cranky blog post about the DET brochure at the time. Then, as my hands were still itching to tear my hair out, I made a free phonics workbook with the same teaching sequence as affordable decodable books, to give parents without much cash a better alternative.

Three years later, parents of five-year-olds have once again been given the same crappy advice in the same brochure, in the 2022 Prep bags. This is the Australian state with the car number-plate slogan “The Education State“, I kid you not.

The brochure only contains the word ‘phonics’ in a section called “Making the most of screen time”, but doesn’t help parents find quality early literacy programs, or consider the difference between them and Reading Eggs, as I have here and here.

There are five nice story books in the Prep bags, suitable for parents to read to children, but not a single decodable book suitable for young beginners to read themselves (unless the book “Hark, It’s Me, Ruby Lee!” is different from “It’s Me, Ruby Lee!” in the Education Minister’s media release).

For a calm, thorough discussion of the difference between the approach recommended by the DET in this brochure, and the approach recommended by reading scientists, see this article: Balanced Literacy or Systematic Reading Instruction? by Prof Pamela Snow.

There has been lots of media discussion about the importance of evidence-based teaching in the early years – recent examples are here, here, and here – and so many wonderful schools and teachers are enthusiastically embracing reading science, that I’d imagined further taxpayer-funded distribution of bad advice to parents wasn’t possible.

Our system not only fails many children with language-based learning difficulties at the start of their education, it bizarrely offers non-evidence-based “Colour Themes” during NAPLAN tests, and this year is making life even harder for the ones who battle on to Year 12, by adding a literacy assessment to the General Achievement Test. The result will be recorded on their graduating certificate for potential employers to see.

Instead of going back to tearing my hair out, I’ve made my January 2019 free Letters and Sounds workbook available again. If you can afford something better, use it instead. If not, and if your child is being taught to read and spell by memorising and guessing words, I hope it helps get them decoding and encoding. The leaflet size Pocket Rockets follow the same phonics teaching sequence, and I think they’re still the cheapest printed decodable books for beginners around.

I look forward to the day when the Victorian DET provides more solidly evidence-based early literacy information and resources to children and parents.

What helps kids read and spell multisyllable words?

19 RepliesVirus rules permitting, the Spelfabet team will present a workshop at the Perth Language, Learning and Literacy conference on 31st March to 2nd April this year.

The title is “Mouthfuls of sounds: Syllables sense and nonsense”, so I’m now scouring the internet for research on how best to help kids read and spell multi-syllable words.

Teaching one-syllable words well seems to be going mainstream

Lots of people seem to have now really nailed synthetic phonics, and are using and promoting it in the early years and intervention (yay!). It’s become so mainstream that I just bought three pretty good synthetic phonics workbooks (Hinkler Junior Explorers Phonics 1, 2 and 3) for $4 each at K-Mart (in among quite a lot of dross, but it’s a start).

Many synthetic phonics programs and resources focus mainly on one-syllable words, most of which only contain one unit of meaning (morpheme), apart from plurals like ‘cats’ (cat + suffix s), past tense verbs like ‘camped’ (camp + suffix ed), and words with ancient, rusted-on suffixes like grow-grown and wide-width.

Multisyllable words contain extra complexity

Synthetic/linguistic phonics programs which target multisyllable words, including spelling-specific programs, vary widely in their instructional approach. Multisyllable words aren’t just longer (in sound terms, though words like ‘idea’ and ‘area’ are short in print), they contain extra complexity:

- Most contain unstressed vowels. When reading by sounding out, we apply the most likely pronunciation(s) to their spellings, often ending up with a ‘spelling pronunciation’ that sounds a bit like a robot, with all syllables stressed. We then need to use Set for Variability skills (the ability to correctly identify a mispronounced word) to adjust the pronunciation and stress the correct syllable(s).

This can mean trying out different stress patterns, and sometimes also considering word type – think of “Allow me to present (verb) you with a present (noun)”. Homographs often have last-syllable stress if they’re verbs, but first syllable stress if they’re nouns.

- Prefixes and suffixes change word meaning/type, they don’t just make words longer e.g. jump (simple verb), jumpy (adjective), jumped (past tense/participle), jumping (present participle), jumpier (comparative), jumpiest (superlative), jumpily (adverb), and the creature you get when you cross a sheep with a kangaroo, a wooly jumper (agent noun, ha ha). I write ‘wooly’ not ‘woolly’ (though both are correct), because it’s an adjective not an adverb: wool + adjectival ‘y’ suffix, as in ‘luck-lucky’ and ‘boss-bossy’, not wool + adverbial ‘ly’ suffix, as in ‘real-really’ and ‘foul-foully’.

- Word endings often need adjusting before adding suffixes: doubling final consonants (run-runner), dropping final e (like-liking) and swapping y and i (dry-driest). Kids need to learn when to adjust, and when not to, so they don’t over-adjust and end up with ‘open-openning’, ‘trace-tracable’, and ‘baby-babiish’.

- Co-articulation (how sounds shmoosh together in speech) often alters how morphemes are pronounced when they join – compare the pronunciation of ‘t’ in ‘act’ and ‘action’. Sometimes this also results in spelling changes e.g. the ‘in‘ prefix in ‘immature’, ‘imbalance’, ‘impossible’ (/p/, /b/ and /m/ are all lips-together sounds), ‘illegal’, ‘irrelevant’, ‘incompetent’ and ‘inglorious’. ‘In’ is pronounced ‘ing’ at the start of words beginning with back-of-the-mouth /k/ and /g/, like the ‘n’ in ‘pink’ and ‘bingo’.

- Reading longer words requires a lot more trying-out different sounds, particularly flexing between checked and free (or ‘short/long’) vowels, as in cabin-cable, ever-even, child-children, poster-roster, unfit-unit. Vowel sounds in base words often change when suffixes are added, e.g. volcano-volcanic, please-pleasant, ride-ridden, sole-solitude, study-student, south-southern (word nerds, look up Trisyllabic Laxing for more on this).

- Many word roots, like ‘dict’, ‘spect’, ‘fract’ and ‘path’, aren’t English words in their own right, but still mean something. However, teaching morpheme meanings may not have much benefit for decoding, fluency, or even vocabulary or comprehension (see Goodwin & Ahn (2013) meta-analysis of morphological interventions).

- Spellings that look like digraphs sometimes represent two different sounds in different syllables e.g. shepherd, pothole, area, stoic, away, koala (see this blog post), again requiring flexible thinking about how to break words up.

I use the Sounds-Write strategy to help kids read and spell multisyllable words, which doesn’t teach spelling rules, syllable types, or other unreliable, wordy things. The Phono-Graphix and Reading Simplified approaches are similar.

However, Sounds-Write doesn’t have an explicit focus on morphemes (well, maybe their new Yr3-6 course does, I haven’t done that yet), so I’ve also been using various morphology programs and resources: books by Marcia Henry, Morpheme Magic, games like Caesar Pleaser and Breakthrough To Success, Word Sums, the Base Bank, and the Spelfabet Workbook 2 v3 for very basic prefixes and suffixes. However, I need a better grip on the relevant research and its implications for practice.

Video discussion on syllable issues

There’s an interesting video of a discussion about research on syllable issues between Drs Mark Seidenberg, Molly Farry-Thorn and Devin Kearns (you might know his Phinder website) on Youtube, or click here for the podcast.

I always want to shout “Speak up, Molly!” when watching these discussions, because she doesn’t say much, but what she does say is usually great. Near the end of this video, she summarises the implications for teaching. Here’s my summary of her summary:

- Explicit teaching about syllable types takes time, adds to cognitive load and takes kids out of the process of reading, so try to keep it to a minimum in general instruction.

- Children who aren’t managing multisyllable words after general instruction may need to be explicitly taught vowel flexing, and/or about syllable types.

- Group words in ways that make the patterns/regularities and clear, and help children practise vowel flexing.

- It can be helpful for teachers to know a lot about syllables, rules etc, but that doesn’t mean it all needs to be taught.

Dr Kearns then goes further, saying he suggests NOT teaching syllable types and verbal rules, apart from basic things like ‘every syllable has a vowel’. Instead, he recommends demonstration of patterns and then lots of practice. Many children with literacy difficulties have language difficulties, so verbal rules can overwhelm/confuse them, and aren’t necessary when skills can be learnt via demonstration and practice.

I’m now trying to get my head around his research paper How Elementary-Age Children Read Polysyllabic Polymorphemic Words (PSPM words) without getting too overwhelmed/confused by terms like ‘Orthographic Levenshtein Distance Frequency’, ‘Laplace approximation implemented in the 1mer function’ and BOBYQA optimization’, and having to go and lie down.

The 202 children studied were in third and fourth grade, attending six demographically mixed schools in the US. This was quite a complex study with multiple factors and measures, so I won’t try to summarise the methods and results, but instead skip to what I think are the main things it suggests for teaching/intervention (but please read it yourself to be sure):

- Strong phonological awareness helps kids read long words, though it may make high-frequency words a little harder, and low-frequency words a little easier. It may help kids link similar sounds in bases and affixed forms, e.g. grade-gradual.

- Strong morphological awareness also helps kids read long words. It’s more helpful than syllable awareness. Processing a whole morpheme is more efficient than processing its component parts, and since morphemes carry meaning, they may help with vocabulary access.

- It helps to know sound-spelling relationships and how to try different pronunciations of spellings in unfamiliar words, especially vowels.

- Having a large vocabulary helps too, as children are more likely to find a word in their oral language system which matches (more or less, via Set for Variability) their spelling pronunciation. Children with large vocabularies might also persist longer in the search for a relevant word.

- High-frequency long words, and words with very common letter pairs (bigrams), are easier to read than low-frequency words and ones with less common letter pairs.

- Most kids learn to process morphemes implicitly in the process of learning to read long words, but struggling readers have more difficulty extracting information implicitly, so many need to be explicitly taught to do this. Strategic exposure and practice is more likely to produce implicit statistical learning than teaching rules, meanings etc.

- It’s easier to process base words that don’t change in affixed forms (e.g. appear-appearance) than ones that change a bit (e.g. chivalry-chivalrous). Kids with weak morphological awareness may need to be taught awareness of both.

- Knowing many derived words’ roots (e.g. the ‘dict’ in ‘contradict’, ‘predict’, ‘dictionary’, ‘dictate’, ‘addict’, ‘valedictory’, and ‘verdict’) makes it more likely the reader will be able to use root word information to read long words.

- Knowledge of orthographic rimes doesn’t seem to help kids read long words. Kearns calls these ‘phonograms’: the vowel letter and any consonant letters following it in a syllable e.g. the ‘e’ and ‘ict’ in ‘predict’, or the ‘uc’ and ‘ess’ in ‘success’.

- This study focussed on reading accuracy but not fluency, and didn’t measure prosodic sensitivity or Set for Variability skills. Further research is needed on these.

If you have insights on any of the above, please write them in the comments below.

Shallow and deep phonics

18 Replies

My last blog post copped a little flak for its focus on the Victorian Education Department’s top two pieces of advice for parents when their children are stuck reading a word, both of which start with the sentence, “Look at the picture.” (see p14 of this document).

This is very bad advice because it directs children’s attention away from the key information required for good word-level reading. It’s based on the idea of multi-cueing/the three-cueing system, which is scientifically-debunked nonsense. A complex but excellent explanation of why can be found here, and the actual role of context in reading is explained well here.

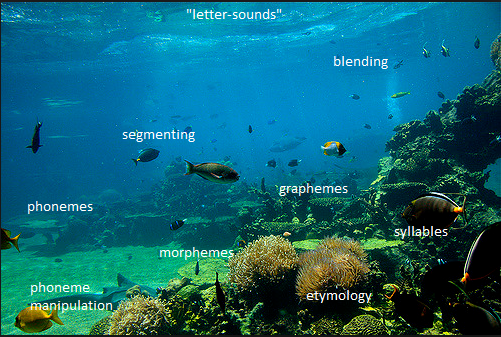

To read an unfamiliar word, children need to take it apart into spellings (graphemes) e.g. “n”, “igh” and “t”, not “ni”, “g” and “ht”, associate these with the relevant speech sounds (phonemes) and blend them into a word. With practice, familiar words are unitised in memory, via a process called orthographic mapping, and no longer need to be sounded out, they become instantly recognised.

Unfamiliar words of more than one syllable must be sounded out a syllable at a time. Earlier syllables must be held in memory while later syllables are worked out, making long words harder.

Once a printed word is converted into a spoken word, its meaning can be accessed, if it’s known. But even if a child doesn’t yet know what a word means (i.e. it’s not yet in their semantic memory), having heard it before (i.e. having it in their phonological memory) kick-starts the process of putting it into long-term memory for instant recognition. Over time the child can learn and refine its meaning(s), and how to use it, by hearing and seeing it in use. (more…)

THIS is a BORING book!

13 Replies

I’ve just watched a great 2016 BBC4 documentary called “B is for book”. It follows a group of London children from their first day at school for a year, and explores how they learn to read.

The kids live on a public housing estate in Hackney, and most speak languages other than English at home.

The film is not currently on the BBC website, but a few people have put it on YouTube. The version I watched is here, and you might like to keep it open in a new tab while you read, so you can quickly find and watch the interesting bits I describe below.

You’ll love all the children, but I was most entranced by a little boy called Stephan. An honest child with a low tolerance for Educrap, he looks and behaves a lot like a little boy I worked with last year, also a twin from public housing inclined to slide under the table.

At 19:42 on the video clock, the two children having the most difficulty learning to read in the film, Maria and Stephan, are asked, “What’s the hardest word you know how to spell?” First, they do this:

Our goal is to develop phoneme proficiency in kids

6 Replies

This is a summary of the second half of an online video seminar entitled “Assessment and Highly Effective Intervention in Light of Advances in Understanding Word-Level Reading” (the first half I recently summarised here), which I hope encourages you to watch the whole thing.

It’s by Dr David Kilpatrick, was recorded at the 2017 Reading in the Rockies conference, and is on the Colorado Dept of Education website. Thanks so much to all those involved in putting this great information in the public domain.

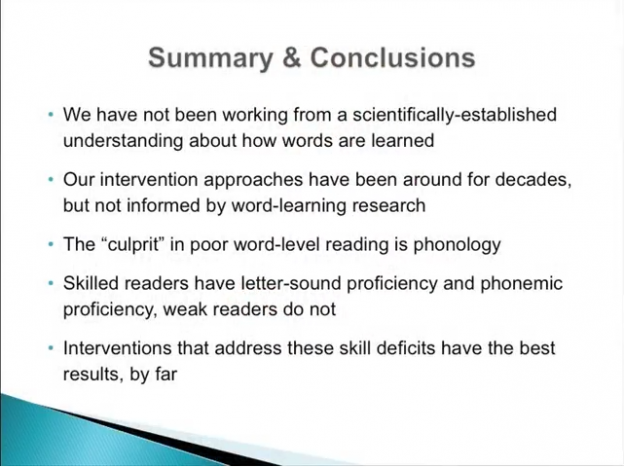

The talk’s summary and conclusions are a good place to start:

- We have not been working from a scientifically-established understanding about how words are learned.

- Our intervention approaches have been around for decades, but are not informed by word-learning research.

- The “culprit” in poor word-level reading is phonology.

- Skilled readers have letter-sound proficiency and phonemic proficiency, weak readers do not.

- Interventions that address these skill deficits have the best results, by far.

Alternative facts about phonics

14 Replies

I’ve just read a new e-book called Reading the Evidence: Synthetic Phonics and Literacy Learning, edited by Margaret M Clark OBE, a UK Visiting and Emeritus Professor who the About The Editor section says “has undertaken research on a wide range of topics and has developed innovate (sic) courses”.

Its announcement elicited some e-eye-rolling from members of the Developmental Disorders of Language and Literacy Network, and jovial suggestions that others buy, read and comment on it, but apparently I’m the only one with nothing more important to do (sigh).

Also on my reading list at the moment is The Influential Mind, about how to persuade people in the face of Confirmation Bias, our tendency to ignore or dismiss evidence that’s not consistent with what we already believe. Confirmation Bias is why presenting scientific data to the climate sceptic in your life never works. You can watch a video about it here.

Reading the Clark et al e-book thus also became an interesting exercise in thinking about my own thoughts. I’d set aside time to read the book in order to write what I hoped would be a thoughtful, informed response, but my brain kept coming up with other ideas. Did it keep switching off because of my own confirmation bias, or because of the standard of what I was reading? (more…)