Australian phonics screening and funding

0 Replies

I haven’t blogged for months because of a hard third COVID-and-flu-cancellations winter, staff changes (we still need another speech pathologist to help with the crazy waiting list, click here for the job ad), a complete website rewrite, and a death in the family. Sigh.

However, many blog-worthy things have kept happening in the science of reading/spelling world. Did you see any of the incredible, free, online PATTAN 2022 Literacy Symposium presentations? Do you know about LDA‘s seminars by US phonemic awareness guru Linnea Ehri and an explosion of local talent in Melbourne on 23 October, and Sydney on the 25th? Tickets are here (but may be close to sold out). I’m pinching myself to have the honour of MCing the Melbourne seminar.

A couple of recent local announcements prompted an excellent blog from Pam Snow, which you can read here, and I’ve been thinking about them too.

Victorian Phonics Screening Check

In 2023, all Year 1 students in my state will do a phonics screening test, to check they’re learning to sound out words, not just memorise and guess them. Excellent.

Many schools still actively encourage guessing and memorising by using predictable texts, multicueing/three-cueing/MSV strategies, and rote-learning of high frequency word lists, and assess early literacy with Running Records.

A Running Record is a bit like assessing a car by walking around it kicking the tyres. Smart kids with weak decoding can appear to be reading. Phonics screening is like lifting the bonnet and checking there’s actually an engine, and the previous driver wasn’t just doing a Fred Flintstone.

There is a federally-funded Literacy Hub Phonics Screening Check, but Victoria’s Phonics Screening Check will consist of items added to the existing English Online Interview. Only employees of the Victorian Education Department can access this, so I can’t tell you much about it. Victoria’s phonics test was piloted earlier in the year, so I hope valid and reliable test items were identified to add to English Online.

Are the skills to be tested in the curriculum?

Victoria’s Year 1 phonics test will be administered in weeks 3-7 of Term 1, so children will have little more than Foundation (first year of schooling) knowledge of phonics. The two Foundation Reading and Viewing Phonics and Word Knowledge standards in the Victorian Curriculum set a very low standard:

- Recognise all upper- and lower-case letters and the most common sound that each letter represents (VCELA146)

- Blend sounds associated with letters when reading consonant-vowel-consonant words (VCELA147)

Taken at face value, these might restrict the Victorian Year 1 phonics screening test’s words to CVCs with spellings like ‘run’, ‘hop’ and ‘fig’, and pseudowords like ‘nim’, ‘wep’ and ‘vab’. Most children who’ve been taught well in Foundation can read much longer/harder words than that.

I hope the process of formulating and using this test, and adapting the state curriculum to the new, taking-phonics-more-seriously Australian curriculum, will prompt our Education Department to spell out which phoneme-grapheme correspondences and morphemes are expected to be learnt, at least in each of the first three years of schooling.

For example, will early Year 1 students be expected to read words with up to five sounds e.g. ‘crust’ and ‘spend’? Words with consonant digraphs like ‘sh’, ‘ch’ and ‘th’? Any vowel digraphs? What about inflectional morphemes like jump-jumps-jumped-jumping, or soft-softer-softest, and compound words? At the moment, this is unclear.

Phonics screening elsewhere

After a long push for more emphasis on early phonics in the UK, the Year 1 Phonics Screening Check was first done across England in 2012. Past versions of UK phonics screening tests are freely available online, here are links to the 2022, 2019 and 2018 versions (2020 and 2021 tests were didn’t happen because of the COVID-19 pandemic).

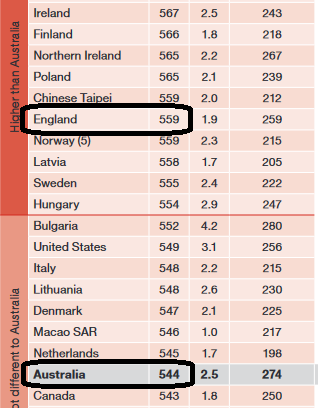

A 2018 National Foundation for Educational Research report said of the UK’s 2016 Progress in Reading Literacy (PIRLS) data for Year 4 students, “The average reading score of students in England was significantly higher than in PIRLS 2006 and 2011, and higher than the majority of other countries.” As you can see from the screenshot of the p5 table of an ACER report on PIRLS 2016 here, English children achieved a Mean score of 559, significantly higher than Australia’s 544. Their extra emphasis on assessing and teaching phonics hasn’t done them any harm.

Two Australian states already screen Year 1 children’s decoding skills. South Australia ran a trial in 2017, then rolled a test out to government schools in 2018, and other schools in 2019. New South Wales had a pilot in 2020 and rollout in 2021. Both tests only seem to be accessible to education department staff, but seem similar to the UK test.

In SA in 2021, 67% of children got the expected 28 out of 40 test words/pseudowords correct. In 2018 only 43% of children got 28 items right. Last year, only 2% of kids couldn’t read any words, down from 4% in 2018. Rural, indigenous and lower socioeconomic kids tended to score below average, more details are here.

In NSW in 2021, 56.7% of students were at or above the expected achievement level, up from 43.3% in the 2020 trial. More details are here. I hope we see a similar early lift in skills in Victoria, and that extra attention and resources for rural, indigenous and disadvantaged kids bring their results closer to average.

Administering and following up the test

Australian Year 1 teachers have been given a couple of days and some training to administer the Year 1 Phonics Check, which is a good start, but more needs to be done to help them make optimal use of the test’s data. Gaps in teachers’ knowledge of scientific approaches to teaching early reading and spelling are now being filled by teachers themselves, in droves, in their own time if necessary. They’re voting with their feet for evidence-based practice, and demanding teaching resources to match. Universities, education departments and publishers should take note, and catch up.

We have a state election at the end of November, and the state Opposition has just promised $220 million for systematic, synthetic phonics training and resources. The downstream benefits of preventing reading failure with such measures are massive, for education, employment, the justice system, health and mental health, you name it.

This election promise is most welcome, and in the context of a ~$90 billion (with a b) state budget, I hope all parties contesting the election will match it. After all, this is The Education State, and all children deserve best educational practice.

Why is the Vic Ed Dept promoting a Fountas and Pinnell assessment?

22 Replies

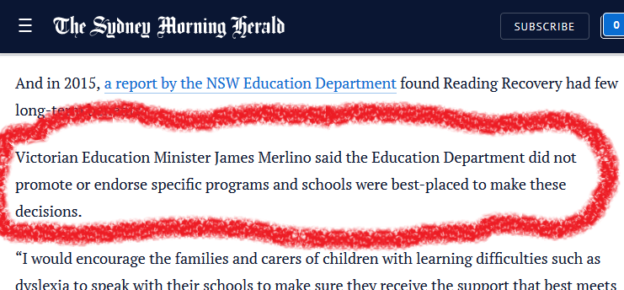

Last year, Victorian Education Minister James Merlino said the Education Department did not promote or endorse specific programs, and schools were best-placed to make these decisions.

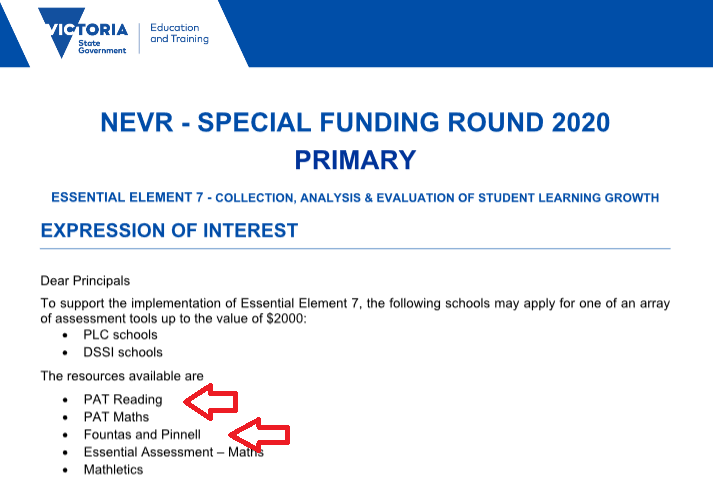

This year, the Victorian Education Department is inviting schools in the North-East region to apply for up to $2000 to be spent on either Fountas and Pinnell or PAT Reading assessments, or a choice of three maths assessments:

The extra funds and emphasis on data-driven instructional decision-making are welcome, but not if they help teachers gather data on how well children can memorise and guess words, or identify children who are struggling with reading comprehension, without clarifying why (decoding? language comprehension? both?).

I’m no expert on mainstream educational assessments for typically-developing older students, but literacy assessments for beginners and strugglers (such as the ones listed here) should assess the skills that matter most for learning to read and spell.

These include phonemic awareness and letter knowledge in beginners, and phonological memory, rapid automatised naming, word and pseudoword reading and spelling in strugglers. These assessments can identify word-level reading/dyslexia-type difficulties, and thus powerfully inform effective instructional decision-making.

Children who seem to have oral language comprehension problems, which also affect reading comprehension, should be referred to a speech pathologist. Children whose comprehension problems arise from pedagogy that prioritises form over content need their teachers to read The Knowledge Gap by Natalie Wexler.

I have only once administered a Fountas and Pinnell assessment, and it left me scratching my head. I just don’t get the whole balanced literacy/guided reading headspace, which has its roots in the now-debunked idea that reading is a psycholinguistic guessing game.

You might already have watched the US Reading League video of psychologist Steve Dykstra unpacking the statistics in the “gold standard” study on Fountas and Pinnell’s Leveled Literacy Intervention program, showing the program was ineffective, though since most teachers don’t know how to read the statistics, they believe the marketing materials, and keep buying it. This doesn’t exactly build my confidence in the validity or reliability of Fountas and Pinnell assessments.

On the assessment page of the Fountas and Pinnell website, you’ll see that the Benchmark Level Assessment assesses “students’ independent and instructional reading levels according to the F&P Text Level Gradient™“. The last time I looked, this gradient did not reflect the sequence of sounds, spelling patterns and word parts being taught in literacy lessons.

Fountas and Pinnell books for beginners are predictable/repetitive texts, which don’t simplify spelling patterns, and thus tend to encourage children to memorise and guess words, not decode them. I’d be (pleasantly) surprised if their assessments don’t reflect the same logic.

The PAT is the other reading test North-East region schools are currently allowed to buy with this new funding. The Australian Council for Educational Research sells the PAT tests, and its website says that the “Progressive Achievement Tests in Reading assess students’ reading comprehension skills, vocabulary knowledge and spelling”. It doesn’t say anything about word-level reading or phonemic awareness.

The PAT Reading test might be just what schools in the North-East region most need right now, but it might not be. Schools teaching children phonemic awareness and systematic, explicit phonics, and with a strong Response To Intervention approach, are very likely to need other assessments to document the progress of some students, for good, scientifically-based reasons.

Education Minister James Merlino should clarify that he meant what he said last year, and let schools propose other valid, reliable assessments for purchase with this additional funding. Taxpayers’ money should only be spent on valid, reliable assessments that are consistent with current scientific knowledge about how children learn to read and spell.

The UK Phonics Check could help reduce teacher workloads

10 Replies

There’s an article in yesterday’s Age newspaper about a proposal from literacy expert Dr Jennifer Buckingham for compulsory use of the UK Phonics check with Australian first grade children. Rather than trying to paraphrase it, I encourage you to read the proposal yourself, it’s in plain English and based on a motza of scientific evidence.

Any teacher, school or interested person can already use the UK Phonics Check. It’s quick, free, simple, downloadable and a useful assessment of early reading skills. Some Australian schools already use it. Click here for the 2016 version.

The test asks children who’ve had about 18 months of literacy instruction to read 20 real words like “chin”, “queen” and “wishing”, plus 20 made-up words like “doil”, “charb” and “barst”.

Since its introduction in England in 2012, the proportion of children passing the Phonics Check has increased each year, and the proportion of children below the expected standard on Year 2 reading tests has fallen by a third. The achievement gap between wealthier and poorer students has also narrowed. Yay to that. (more…)

Helping teenagers with literacy

10 Replies

The other day our state Education Minister announced $72.3 million extra dollars will be spent over four years helping struggling secondary students, specifically kids who haven’t met Year 5 NAPLAN benchmarks.

Woo hoo to that, I say. But if it’s spent on doing the same sorts of things that didn’t work in primary school, it will be a waste.

Secondary school students with poor decoding skills and very little ability to spell generally need a good initial blast of synthetic phonics to build their awareness of sounds in words and knowledge of spelling patterns, followed up by work on vocabulary, comprehension and fluency. I’ve been doing this type of work for 14 years, in conjunction with the world’s most fabulous integration teacher and aides. We’re yet to find someone we can’t teach to read, including students with intellectual disability, language disorder and English as a second or third language.

Here’s roughly what I’d do and buy if I were a decision-maker in a secondary school with a number of students who have encoding/decoding difficulties.

Literacy policy

1 RepliesAn article yesterday in The Conversation called "'Biggest Loser' policy on literacy will not deliver long-term gains" has urged caution at the government's $22 million for Direct Instruction in remote Aboriginal communities.

Stewart Riddle from the University of Southern Queensland writes that the Federal government can't expect to axe the Gonski education funding model and indigenous community health and education programs, "and then turn around and claim that a sparkly new program will somehow 'fix' Indigenous literacy."

Well, I agree, I'm angry about the big cuts too. But I think the Direct Instruction funding is probably a good thing, and is likely to give the Aboriginal kids involved a good start on literacy.

No, it won't fix all the problems, but the muddled approach Riddle recommends is more likely to leave them simply unable to get words on and off the page.

"Skilling and drilling"?

Riddle argues that the Direct Instruction program that has received the $22m funding is about "skilling and drilling students to the point of exhaustion, in order to get the most visible results possible (i.e. increased NAPLAN scores) in the shortest time".

He doesn't cite any evidence to support this controversial statement, or explain exactly what other sorts of results might be more desirable than fast improvements on national literacy test scores. He argues that other things are probably more important than test scores.

Phonics resources

0 Replies

In the UK, synthetic phonics is now official government policy for early literacy-teaching, and primary schools that spend up to $9200 on accredited synthetic phonics resources and training before March 2013 get half of it paid for by the government.

I want what they’ve got.

All government-funded schools with Year 1 and 2 students (5-7 year olds) are eligible for this support to buy synthetic phonics resources. Not sure whether large and small schools get the same amount, and it looks like secondary schools miss out.

So actually, I want what they’ve got, but with a bit more equity.

Have a look at the incredible catalogue of phonics resources they can choose from, with its rather strange title “The Importance of Phonics” (2021 update, page no longer available).