What helps kids read and spell multisyllable words?

19 RepliesVirus rules permitting, the Spelfabet team will present a workshop at the Perth Language, Learning and Literacy conference on 31st March to 2nd April this year.

The title is “Mouthfuls of sounds: Syllables sense and nonsense”, so I’m now scouring the internet for research on how best to help kids read and spell multi-syllable words.

Teaching one-syllable words well seems to be going mainstream

Lots of people seem to have now really nailed synthetic phonics, and are using and promoting it in the early years and intervention (yay!). It’s become so mainstream that I just bought three pretty good synthetic phonics workbooks (Hinkler Junior Explorers Phonics 1, 2 and 3) for $4 each at K-Mart (in among quite a lot of dross, but it’s a start).

Many synthetic phonics programs and resources focus mainly on one-syllable words, most of which only contain one unit of meaning (morpheme), apart from plurals like ‘cats’ (cat + suffix s), past tense verbs like ‘camped’ (camp + suffix ed), and words with ancient, rusted-on suffixes like grow-grown and wide-width.

Multisyllable words contain extra complexity

Synthetic/linguistic phonics programs which target multisyllable words, including spelling-specific programs, vary widely in their instructional approach. Multisyllable words aren’t just longer (in sound terms, though words like ‘idea’ and ‘area’ are short in print), they contain extra complexity:

- Most contain unstressed vowels. When reading by sounding out, we apply the most likely pronunciation(s) to their spellings, often ending up with a ‘spelling pronunciation’ that sounds a bit like a robot, with all syllables stressed. We then need to use Set for Variability skills (the ability to correctly identify a mispronounced word) to adjust the pronunciation and stress the correct syllable(s).

This can mean trying out different stress patterns, and sometimes also considering word type – think of “Allow me to present (verb) you with a present (noun)”. Homographs often have last-syllable stress if they’re verbs, but first syllable stress if they’re nouns.

- Prefixes and suffixes change word meaning/type, they don’t just make words longer e.g. jump (simple verb), jumpy (adjective), jumped (past tense/participle), jumping (present participle), jumpier (comparative), jumpiest (superlative), jumpily (adverb), and the creature you get when you cross a sheep with a kangaroo, a wooly jumper (agent noun, ha ha). I write ‘wooly’ not ‘woolly’ (though both are correct), because it’s an adjective not an adverb: wool + adjectival ‘y’ suffix, as in ‘luck-lucky’ and ‘boss-bossy’, not wool + adverbial ‘ly’ suffix, as in ‘real-really’ and ‘foul-foully’.

- Word endings often need adjusting before adding suffixes: doubling final consonants (run-runner), dropping final e (like-liking) and swapping y and i (dry-driest). Kids need to learn when to adjust, and when not to, so they don’t over-adjust and end up with ‘open-openning’, ‘trace-tracable’, and ‘baby-babiish’.

- Co-articulation (how sounds shmoosh together in speech) often alters how morphemes are pronounced when they join – compare the pronunciation of ‘t’ in ‘act’ and ‘action’. Sometimes this also results in spelling changes e.g. the ‘in‘ prefix in ‘immature’, ‘imbalance’, ‘impossible’ (/p/, /b/ and /m/ are all lips-together sounds), ‘illegal’, ‘irrelevant’, ‘incompetent’ and ‘inglorious’. ‘In’ is pronounced ‘ing’ at the start of words beginning with back-of-the-mouth /k/ and /g/, like the ‘n’ in ‘pink’ and ‘bingo’.

- Reading longer words requires a lot more trying-out different sounds, particularly flexing between checked and free (or ‘short/long’) vowels, as in cabin-cable, ever-even, child-children, poster-roster, unfit-unit. Vowel sounds in base words often change when suffixes are added, e.g. volcano-volcanic, please-pleasant, ride-ridden, sole-solitude, study-student, south-southern (word nerds, look up Trisyllabic Laxing for more on this).

- Many word roots, like ‘dict’, ‘spect’, ‘fract’ and ‘path’, aren’t English words in their own right, but still mean something. However, teaching morpheme meanings may not have much benefit for decoding, fluency, or even vocabulary or comprehension (see Goodwin & Ahn (2013) meta-analysis of morphological interventions).

- Spellings that look like digraphs sometimes represent two different sounds in different syllables e.g. shepherd, pothole, area, stoic, away, koala (see this blog post), again requiring flexible thinking about how to break words up.

I use the Sounds-Write strategy to help kids read and spell multisyllable words, which doesn’t teach spelling rules, syllable types, or other unreliable, wordy things. The Phono-Graphix and Reading Simplified approaches are similar.

However, Sounds-Write doesn’t have an explicit focus on morphemes (well, maybe their new Yr3-6 course does, I haven’t done that yet), so I’ve also been using various morphology programs and resources: books by Marcia Henry, Morpheme Magic, games like Caesar Pleaser and Breakthrough To Success, Word Sums, the Base Bank, and the Spelfabet Workbook 2 v3 for very basic prefixes and suffixes. However, I need a better grip on the relevant research and its implications for practice.

Video discussion on syllable issues

There’s an interesting video of a discussion about research on syllable issues between Drs Mark Seidenberg, Molly Farry-Thorn and Devin Kearns (you might know his Phinder website) on Youtube, or click here for the podcast.

I always want to shout “Speak up, Molly!” when watching these discussions, because she doesn’t say much, but what she does say is usually great. Near the end of this video, she summarises the implications for teaching. Here’s my summary of her summary:

- Explicit teaching about syllable types takes time, adds to cognitive load and takes kids out of the process of reading, so try to keep it to a minimum in general instruction.

- Children who aren’t managing multisyllable words after general instruction may need to be explicitly taught vowel flexing, and/or about syllable types.

- Group words in ways that make the patterns/regularities and clear, and help children practise vowel flexing.

- It can be helpful for teachers to know a lot about syllables, rules etc, but that doesn’t mean it all needs to be taught.

Dr Kearns then goes further, saying he suggests NOT teaching syllable types and verbal rules, apart from basic things like ‘every syllable has a vowel’. Instead, he recommends demonstration of patterns and then lots of practice. Many children with literacy difficulties have language difficulties, so verbal rules can overwhelm/confuse them, and aren’t necessary when skills can be learnt via demonstration and practice.

I’m now trying to get my head around his research paper How Elementary-Age Children Read Polysyllabic Polymorphemic Words (PSPM words) without getting too overwhelmed/confused by terms like ‘Orthographic Levenshtein Distance Frequency’, ‘Laplace approximation implemented in the 1mer function’ and BOBYQA optimization’, and having to go and lie down.

The 202 children studied were in third and fourth grade, attending six demographically mixed schools in the US. This was quite a complex study with multiple factors and measures, so I won’t try to summarise the methods and results, but instead skip to what I think are the main things it suggests for teaching/intervention (but please read it yourself to be sure):

- Strong phonological awareness helps kids read long words, though it may make high-frequency words a little harder, and low-frequency words a little easier. It may help kids link similar sounds in bases and affixed forms, e.g. grade-gradual.

- Strong morphological awareness also helps kids read long words. It’s more helpful than syllable awareness. Processing a whole morpheme is more efficient than processing its component parts, and since morphemes carry meaning, they may help with vocabulary access.

- It helps to know sound-spelling relationships and how to try different pronunciations of spellings in unfamiliar words, especially vowels.

- Having a large vocabulary helps too, as children are more likely to find a word in their oral language system which matches (more or less, via Set for Variability) their spelling pronunciation. Children with large vocabularies might also persist longer in the search for a relevant word.

- High-frequency long words, and words with very common letter pairs (bigrams), are easier to read than low-frequency words and ones with less common letter pairs.

- Most kids learn to process morphemes implicitly in the process of learning to read long words, but struggling readers have more difficulty extracting information implicitly, so many need to be explicitly taught to do this. Strategic exposure and practice is more likely to produce implicit statistical learning than teaching rules, meanings etc.

- It’s easier to process base words that don’t change in affixed forms (e.g. appear-appearance) than ones that change a bit (e.g. chivalry-chivalrous). Kids with weak morphological awareness may need to be taught awareness of both.

- Knowing many derived words’ roots (e.g. the ‘dict’ in ‘contradict’, ‘predict’, ‘dictionary’, ‘dictate’, ‘addict’, ‘valedictory’, and ‘verdict’) makes it more likely the reader will be able to use root word information to read long words.

- Knowledge of orthographic rimes doesn’t seem to help kids read long words. Kearns calls these ‘phonograms’: the vowel letter and any consonant letters following it in a syllable e.g. the ‘e’ and ‘ict’ in ‘predict’, or the ‘uc’ and ‘ess’ in ‘success’.

- This study focussed on reading accuracy but not fluency, and didn’t measure prosodic sensitivity or Set for Variability skills. Further research is needed on these.

If you have insights on any of the above, please write them in the comments below.

Affordable basic phonics kit

6 Replies

Thanks to the pandemic, many children seem to have done year or more of disrupted schooling without having learnt to read or spell much. A new batch of Australian five-year-olds start school soon, where many will (happily) be taught the systematic, explicit phonics that’s helpful for all, harmful for none and crucial for some*, but many won’t.

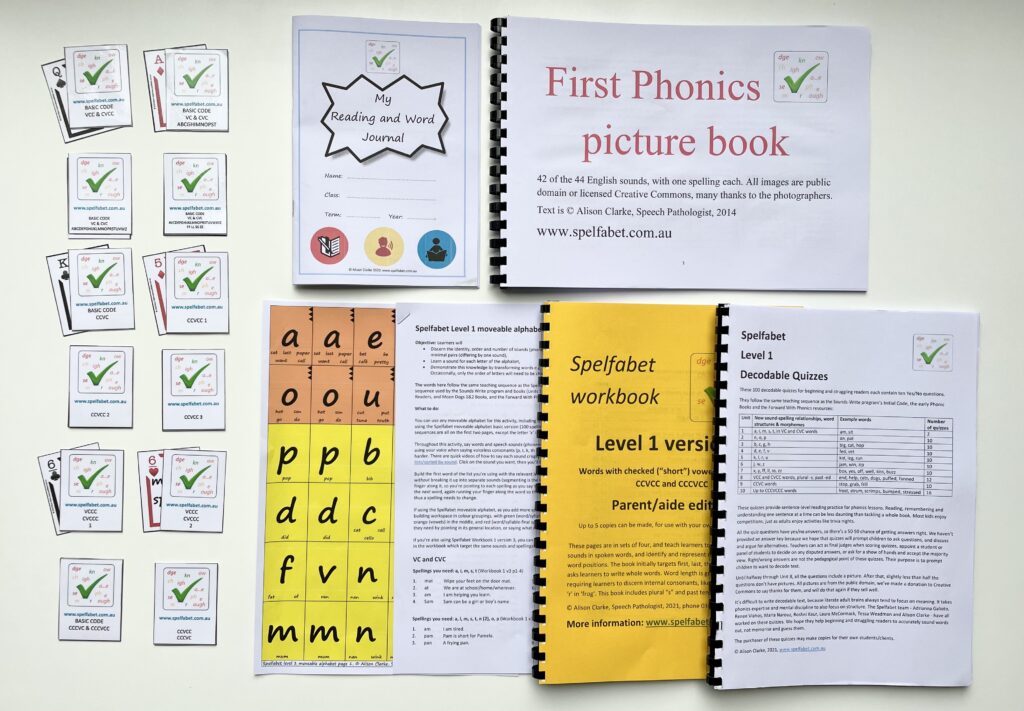

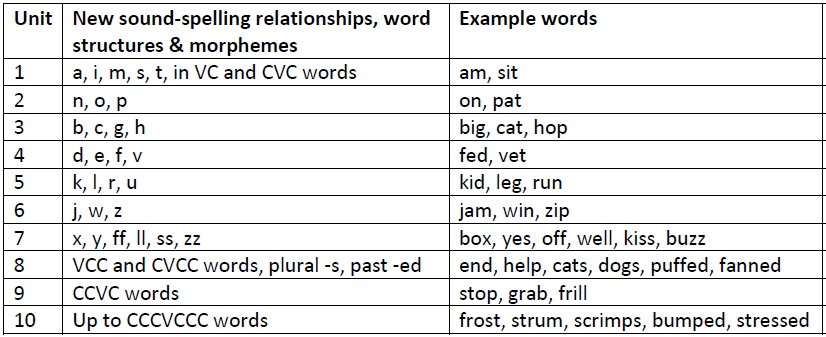

The download-and-print Spelfabet Level 1 kit aims to equip you to help beginners and strugglers of any age learn to read and spell one-syllable words with up to seven sounds. The kit follows this teaching sequence (the same as the Sounds-Write program):

The kit contents are a workbook, quizzes, moveable alphabet, word-building sequences, playing cards, reading journal and phonics picture book. The only difference between the parent/aide kit and the teacher/clinician kit is how many copies of the workbook you may print (5 or 30 copies).

All the items in this kit are available separately from the Spelfabet website, except the simplified Moveable Alphabet, which contains only the spellings needed for Level 1. However, it’s cheaper to get the kit than each item separately ($55 including GST for the parent/aide version and $65 for the teacher/clinician one).

Decodable books for reading practice which follow the same teaching sequence include the Units 1-10 Sounds Write books including free e-books, the Units 1-10 Dandelion and Moon Dogs books from Phonic Books, and the printable Drop In Series Levels 1 and 2.

If this kit is too basic for your learner(s), more difficult kits will be available soon.

* See article by Catherine Snow and Connie Juel (2005) at https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2005-06969-026

New Phonics With Feeling books and author interview

3 Replies

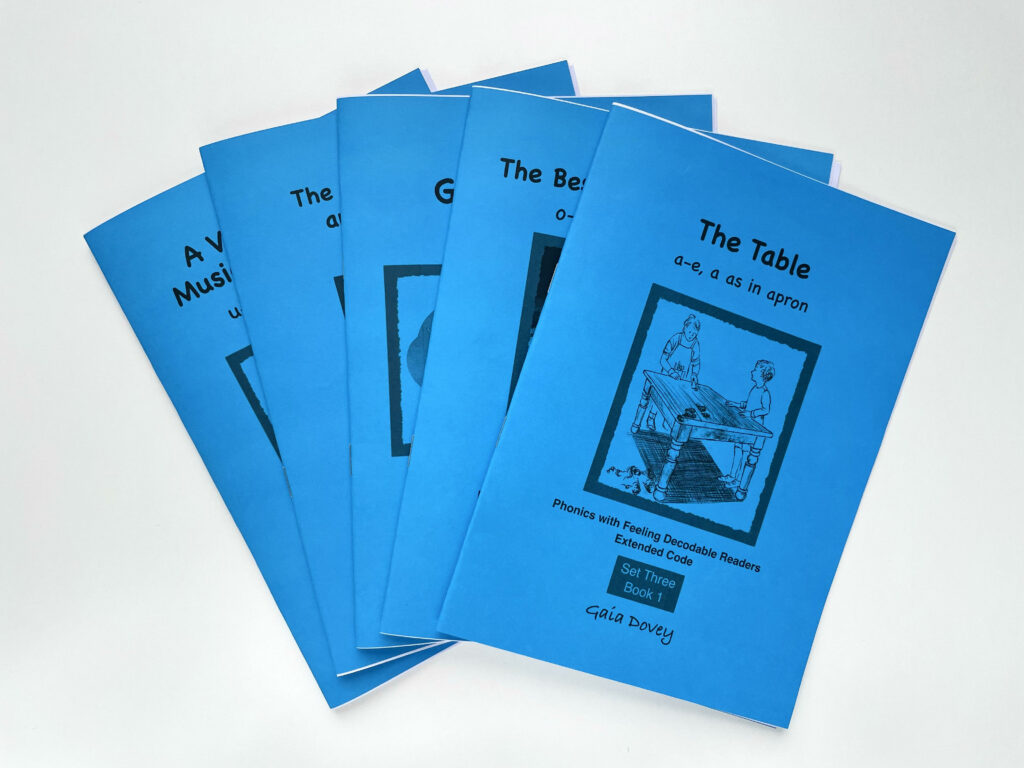

Set Three of the download-and-print Phonics With Feeling Extended Code readers are now available from the Spelfabet shop.

These books provide lots of reading practice of words with single-letter ‘long’ vowel sounds, as in ‘apron’, ‘being’, ‘final’, ‘open’ and ‘using’.

Many of these are suffixed forms of the ‘split vowel’/’silent final e’ spellings in Set Two e.g. make-making, Swede-Swedish, ice–icy, hope-hoped, cute-cutest. Word lists at the start of each book make this explicit.

The ‘c’ as in ‘ice’ and ‘g’ as in ‘age’ spellings, which often occur with these spellings, are practised in the Extended Code Set One books.

The Set Three books also include the ‘short’ vowel sounds, as in ‘at’, ‘red’, ‘in’, ‘on’ and ‘up’. When tackling new words, children should be encouraged to try both sounds for a vowel letter, if the first sound they try doesn’t produce a word that makes sense. This requires phoneme manipulation skills, and the knowledge that a spelling can represent more than one sound.

Like the other Phonics With Feeling books, the Set Three books have a print-5-copies version (parent/aide) for 40c per print, and a bulk print-30-copies version (teacher/clinician) for 20c per print. Our free quizzes (downloadable or on Wordwall) have been updated to include Set Three.

Teresa Dovey (pen name Gaia Dovey, as that’s what her grandkids call her) is the author of the Phonics With Feeling decodable readers. Here’s a 15-minute interview in which she discusses why she started writing the books, why they’re called Phonics With Feeling, her academic background in English Literature, what the books are like, who they’re for, how they can be used, and some of the feedback she’s received on them.

We hope these books make decodable text interesting and enjoyable for children, and affordable for adults, and that they help kids learn to decode as well as Teresa’s grandkids, so they can go on to enjoy reading whatever they choose.

If you’ve tried the books, please share any comments or feedback you have below.

1000 decodable quiz questions

7 RepliesAt last, our 100 download-and-print phonics quizzes for beginning readers are available here. Each has ten questions, and fits on an A4 page. Most questions have pictures. You can download a free sample of ten of them here. Here’s a 2 minute video about them.

Kids aren’t usually keen on tests, but enjoy quizzes, just as adults enjoy trivia nights. Reading and understanding a sentence at a time can be less daunting than reading, remembering and understanding a book, even a short one.

These quizzes follow the same teaching sequence as Sounds-Write Units 1-10, and the early Phonic Books and Forward With Phonics resources, since our client base is mostly struggling older learners. If you’re using a slightly different phonics teaching sequence, just check that you’ve taught all the sound-spelling relationships in each quiz before using it, perhaps as a review activity.

Writing decodable text is hard work. The literate adult brain constantly wants to focus on meaning not structure. It takes lots of discipline to think of good questions that don’t contain words that are too hard, especially at the early levels. The whole Spelfabet team has been involved in writing these quizzes, and have been extremely tolerant of my initially vague ideas and constant revisions. It’s taken much longer than expected.

We haven’t included an answer key because we hope the quizzes motivate children to ask questions and propose alternative answers/interpretations, argue for a ‘maybe/it depends’ option and otherwise think and talk. You can act as judge, assign a judging panel, or go with the majority view. Right and wrong answers are not as important as prompting children to read accurately and successfully.

We hope beginning and struggling readers enjoy and request these quizzes, and that they help build children’s reading ‘muscle’.

“These are just books kids can read!”

9 RepliesMy new favourite thing is an interview with US mum Jennifer Ose-MacDonald, about how she worked with her local library to create a collection of decodable books. It’s on the excellent Teach My Kid To Read YouTube channel.

Jennifer took action after she discovered that her local libraries only had books for beginners and strugglers full of too-hard “bomb words” which deflate their reading confidence. Bomb words. A term we need, I’ll be using it a lot. Brilliant.

Jennifer says (just after the 10 minute mark, if you don’t have time to watch the whole 15 minutes) “there’s a lack of understanding in the general population about what a decodable is, because it has a name, people think that it’s special, or that it’s only for a select group of people, and that’s a misunderstanding of what they are. So I think my new role is helping people understand that THESE ARE JUST BOOKS KIDS CAN READ! That’s all they are, they’re books kids can read. And if you want kids to read books, why don’t you look at these? And you’ll see that if you pick the books that are at the right skill level, they can get through a page without having to stop and get frustrated over a word that shouldn’t be there in the first place”.

This is the first in what looks like a series of videos, so I look forward to the next one.

We all want children to experience the joy of reading. Typical books for beginners offer joy and hope, but that hope is too often dashed. Decodable books offer joy and confidence.

Thanks to Heidi from Dyslexia Victoria Support for pointing out this video, and to the people at Teach My Kid To Read for making it. It made my day, I hope it made yours too.

New printable decodables and free quizzes

11 RepliesI’ve just made free follow-up Wordwall quizzes for all the Phonics With Feeling decodable readers, including three new Extended Code Set 1 books now available (update January 2022: There are now 5 books in this set).

The 41 quizzes, of ~20 questions each, are all in a folder called Phonics With Feeling here. I’ve also made printable versions without pictures, which you can download for free here.

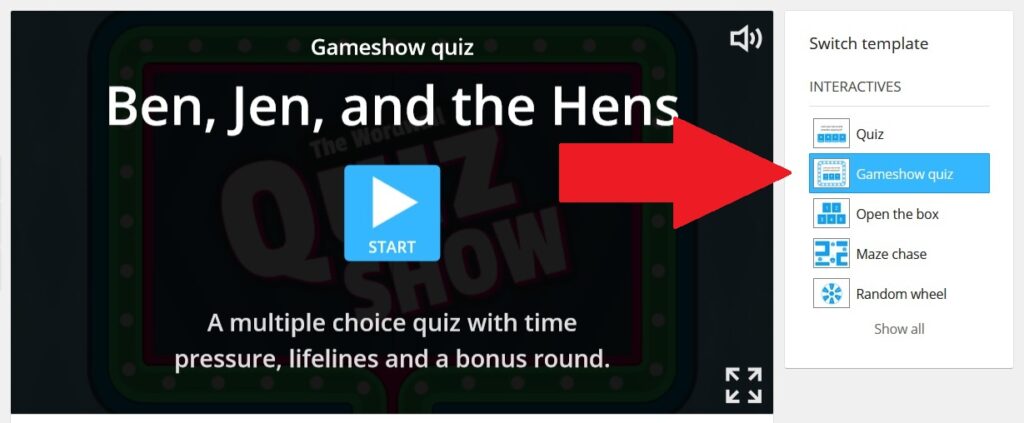

The online quizzes are made in the basic Wordwall Quiz format, but you can use them in Gameshow Quiz format for a few more bells and whistles, which many children enjoy, though the timer freaks some highly anxious children out. Click at the right of the startup screen if you want to switch to Gameshow format:

Click on the Share button below each quiz to set it as an after-reading assignment.

The quiz questions are comprehension/concept questions about the Phonics With Feeling readers, which provide extra Really-Nail-That-Pattern practice for children in Years 1 or 2, or slightly older struggling learners. The Initial Code readers are also suitable for many children approaching the end of their first school year (we Victorians call them Preps). Each quiz is written at the same decoding level as the relevant reader.

The quizzes contain some deliberate garden path questions, and traps for picture-guessers and kids inclined to read the start and end of words, and guess the middles, e.g. “Did Red Hen make a net?” followed by “Did Red Hen make a nest?” I hope this makes skimming kids do a double-take, and look more closely at ALL the letters.

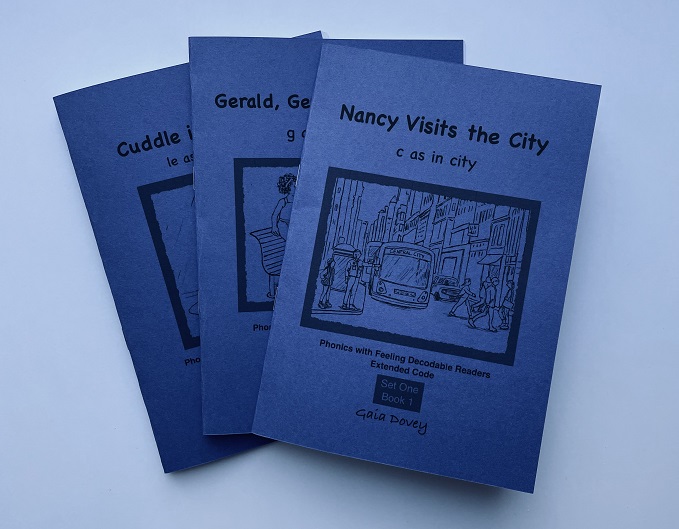

The three new Extended Code Set One Phonics With Feeling readers look like this once you’ve printed them with nice coloured cardboard covers:

These new books target:

- /s/ as in ‘cent’ (spelt C),

- /j/ as in ‘gem’ (spelt G) and

- Unstressed final syllable ‘le’ as in ‘candle’ and ‘middle’.

Like all the other Phonics With Feeling books, the Parent/Aide version allows you to print up to 5 copies of each book for 40c per copy, plus printing and materials costs.

If you want to use the books with a whole class or caseload, the Teacher/Clinician versions allow printing of up to 30 copies of each book, which works out at 20c per print. We hope this allows teachers to use them as class sets, and have a few spares to replace any that get lost, leaked on by drink bottles, chewed by puppies etc.

The download-and-print quizzes don’t have pictures, and may be useful as follow-up paper-based activities, or you might like to turn the questions into Kahoot!s, or other games/competitions. If my quizzes are too long for your students, just leave some of the questions out, and tweak the remainder. Save yourself the brain-frying experience of writing decodable text from scratch.

40 Phonics with Feeling books are currently available, but I’ve made 41 Wordwall quizzes, because the last Set Seven book has two stories in it – ‘Sue and the Glue’ and ‘Robot Andrew’. The Phonics With Feeling Extended Code Set Three should be available in November, and will target single-letter ‘short/long’ vowels, providing children with many opportunities to practise ‘flipping’ vowel sounds till they get a word they know that makes sense in context (e.g. the ‘o’ in ‘poster’ and ‘roster’).

Still too hard for your learners? Try the new, free Sounds-Write texts

If these books and quizzes are too hard for your kids, and you need more basic decodable texts, Sounds-Write has a cute new free e-book First Steps Collection about strange pets (including a bug, a fox, a crab, a skunk, a moth, a chimp and a squid), for Units 4-11 of Sounds-Write. They’re a bit easier than the original Sounds Write books. Printed versions are also available, though I think at the time of writing they haven’t yet arrived at Australian suppliers DSF, Soundality or Rise Literacy.

If even those books are too difficult for your learner, we’ve made some 10-question WordWall quizzes for Sounds-Write Units 1-3:

- Unit 1 (I realised two of my local MPs are called Tim and Sam, so it’s nonfiction quiz)

- Unit 2 (the featured Pam is Prof Pamela Snow, again very much nonfiction)

- Unit 3.

We’re working on quizzes for later units now, if you can smell our brains frying.

Hope you find at least some of this useful, especially those of you who are still (like us, sigh) in COVID-19 lockdown. Stay well!

The sweaty sounding-out stage builds reading muscle

26 RepliesWe want young children’s lives to be fun, and free of struggle and hard work. We want them to enjoy reading, like we do. So listening to young children reading simple books containing the spelling patterns they’ve been taught in phonics lessons (decodable books) can be quite painful, and a little confronting, for adults.

They grunt and groan and sweat their way through the words. Most of their cognitive horsepower gets used up just extracting the words from the page, and they don’t understand much of what they’ve read. It’s certainly not fluent. It looks and sounds more like hard slog than fun.

However, inside a child’s brain, something extraordinary is happening. They’re creating a new brain circuit linking the visual areas at the back of the brain with the language areas on the left. They’re shifting some tasks usually done on the left side over to the right hemisphere, and repurposing left hemisphere brain cells for reading. See this 2015 blog post for the science behind this.

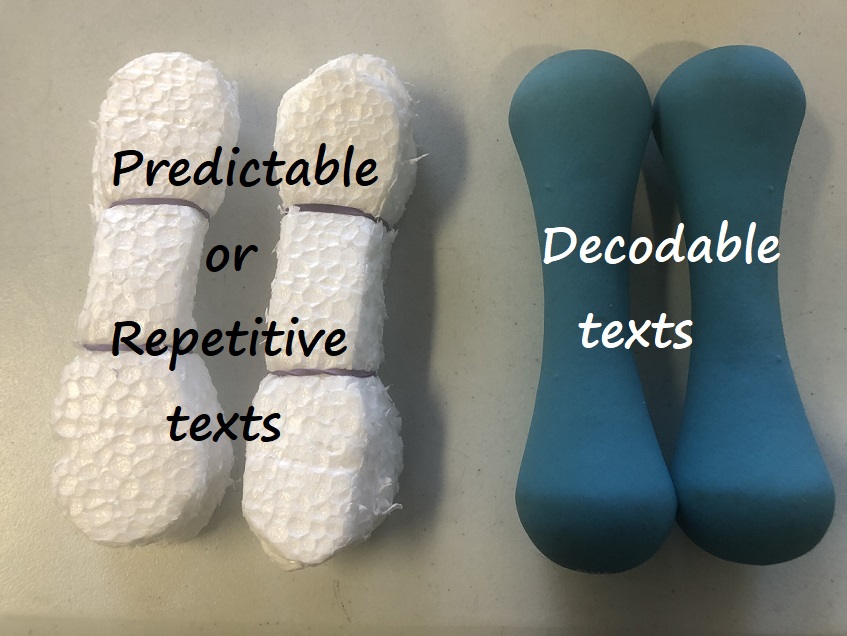

Lack of understanding of the importance and value of this stage is probably how predictable/repetitive texts got a foothold in early education. I detest them, because they teach children to fake fluent reading by memorising repetitive sentence stems and guessing the rest from pictures. This is a lot easier for adults to listen to, and if you believe reading should be fluent and easy from the start, it sounds like real reading.

If you went to a gym and they told you their weights were made of polystyrene because lifting real weights makes people sweat and grunt and isn’t pretty to watch, you’d walk straight out.

Predictable/repetitive texts are like fake weights at the gym. They make the exercise easier and less painful to watch, but they don’t build reading muscle.

Next time you’re watching a child slowly and laboriously sounding out words in a well-selected decodable book, cheer them on. Don’t wish it wasn’t hard or try to make it easier. All that sweating and striving is because they’re building their reading brain, which is such a powerful and wonderful thing to do, and well worth the effort.