Summer holiday groups at Spelfabet

0 Replies

Bookings are now open for our intensive explicit, systematic synthetic phonics therapy groups in the week of 15-19 January 2024.

These are for young children (in school Years F-2 in 2023) who need extra help with learning to read and spell words by sounding them out.

Each group will run for an hour a day, and include plenty of games and fun. We will provide daily homework to complete and bring to the next session.

The groups will be:

| Time | Skill level | Example words targeted |

| 8.45am to 9.45am | Beginners: VC and CVC words. | at, in, hop, bus, red, fan, big |

| 10.15am-11.15am | Adding common suffixes to base words, doubling final consonants as needed. Introducing three “long” vowels with consonant-e/split/silent final e spellings, and when to drop final e before adding a suffix. NB if you have a Year 3-4 child who needs this level of work, we may run a second group for them at 11.45am. | bat-batting, swim-swimmer, hop-hopped, run-runny, shade-shady, time, timer, hope, hoping |

| 11.45am to 12.45pm | Adjacent consonants: CVCC, CCVC, CCVCC, CCCVC, CVCCC. | help, list, trap, stop, crust, strip, jumps |

| 2.00pm to 3.00pm | Consonant digraphs. | wish, chat, fetch, this, when, quick, sing |

We will provide all the necessary resources, including specialist take-home readers. We have a maximum of four children per speech pathologist in our groups, to keep the pace/intensity high. We match children carefully and ask that everyone comes prepared to attend all sessions and do all the homework.

Our groups will be held at our North Fitzroy office in Melbourne’s inner north, with attendance by appointment only. Spaces are limited, and upfront payment for all group sessions is required to secure a child’s place. The cost of a week’s program is $720, which covers all sessions, materials and planning time, plus a brief final report with recommendations. Missed sessions are non-refundable. Private health rebates may apply, depending on your level/type of cover, but Medicare only provides rebates for individual therapy sessions.

Children not already known to us need to attend an assessment session with us before joining a group. This allows us to check whether we have a suitable group, and helps us cater for any special needs/interests. If we don’t have a group matching a child’s skills and needs, we can usually suggest other intervention options.

Please contact Tiana Knights on admin@spelfabet.com.au, (03) 8528 0138 or text 0434 902 249 if you’d like to find out more about these groups, or book an assessment for a struggling reader/speller.

New word-building videos

0 RepliesI’ve made three very short videos (each under 90 seconds) showing how lots of long words are built by adding prefixes and suffixes to base words. The tiles depicted are from the Spelfabet Moveable Alphabet and Affixes, many of which flip over, making it easy to demonstrate juncture changes e.g. how ‘y’ changes to ‘i’ in ‘funny-funnier’, and final consonants double in ‘run-running’ and ‘hop-hopping’.

The aim is to minimise wordy explanation, and maximise demonstration, so I’ll stop explaining them now, and let them speak for themselves. Hope you like them.

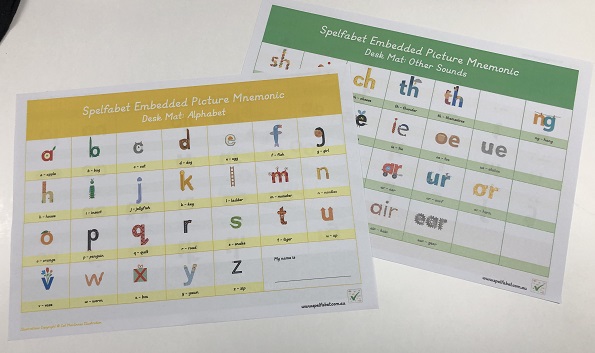

Embedded Picture Mnemonic bookmarks and desk mats

0 RepliesHelp beginners link speech sounds and letters/spellings with our new, printable embedded picture mnemonic bookmarks and desk mats.

The bookmarks are single-sided, with one mnemonic for each letter of the alphabet. Five print to an A4 page. Save, print, laminate and cut up for distribution to literacy beginners. If/when some are lost/damaged, just print extras.

The desk mats have the alphabet on one side, and a mnemonic for each of the other sounds on the flip side. Print just the first side for beginners, or both sides to show learners that there are more sounds than letters, so many are written with letter combinations.

There are three versions, to suit different accents and preferences, all with the new y/yawn mnemonic:

- A version for most Australian, UK, NZ and other speakers of non-rhotic Englishes, with e/egg, k/key, o/orange, u/up, ur/surf, air/hair and ear/gears.

- A more Aussie version as above, but with k/kangaroo and u/undies (yes! back by popular demand).

- A version for US, Canadian and other speakers of rhotic accents, with e/echo, k/key, o/octopus, u/up, wh/whale, ur/burn, and aw/claw, but no air/hair or ear/gears.

Prices assume each purchaser will print enough for their class/caseload.

We hope you like them!

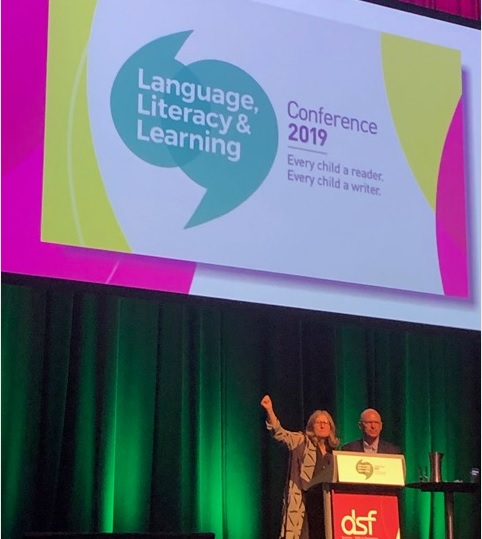

The Language, Learning and Literacy conference – Kathy Rastle

6 RepliesKathy Rastle was another keynote speaker at last week’s great Language, Literacy and Learning conference whose topic is directly relevant to this blog.

You might remember her as a co-author of last year’s influential paper about Ending the Reading Wars, and of this related article (both highly recommended reading).

Hers was the final keynote of the conference, but I met her on the first day. Being a dairy farmer’s daughter who went to Warrnambool High School, I’m still always a little amazed when people with titles like Professor and Head of the Department of Psychology at Royal Holloway, University of London say “hi, I’m Kathy”, and are utterly smiley, nice, and not the least bit pretentious.

Here Kathy is (on the right) with the also-legendary and lovely Lyn Stone (on the left) and Sarah Awesome (AKA Asome) of Bentleigh West PS, (check out their NAPLAN Year 3 spelling gain here!) at the conference Sundowner drinks. However, in the interests of showing proper, gender-neutral academic respect I’ll use her surname from now on.

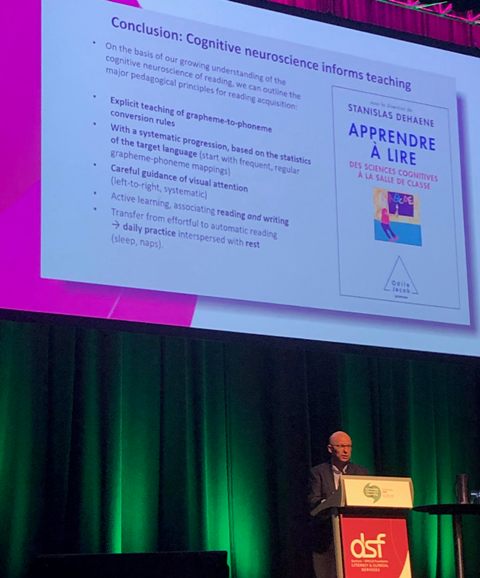

The Language, Literacy and Learning conference – Stanislas Dehaene

17 Replies

I’ve just been to a fantastic conference in Perth, organised by the Dyslexia SPELD Foundation of WA. I missed the first one in 2017 because of a diary facepalm, and have been kicking myself and looking forward to this conference ever since.

I took my laptop, imagining I’d find time each evening to write a riveting blog post about the day’s new learning. Instead I kept going out for drinks with colleagues, sorry not sorry, but a room full of like-minded colleagues is an irresistible thing of beauty and a joy forever.

Then I was going to write a blog post on the plane, but found myself chatting to the nice and distractingly handsome young bloke sitting next to me, sorry not sorry again. Since then I’ve realised that any blog post that did justice to the whole conference would need to be about a kilometre long. So I’ve decided to just write a few posts about the best bits.

Learning is a process of neuronal recycling

French cognitive neuropsychologist Professor Stanislas Dehaene gave the opening keynote address of the conference. He firstly told us we should forget everything we’ve heard about the differences between the left and right brain.

Young children’s brains are astonishingly flexible and able to reorganise. There are twice as many synapses in a child aged one or two as in an adult. Synapses come and go all the time.

A child whose entire left hemisphere was surgically removed in infancy was still able to learn language and literacy more or less along the usual lines.

Learning to read = establishing a visual interface into the language system

When we learn to read, we establish a new visual interface into the language system. It develops in an area of the brain otherwise used to recognise faces and objects, but the cells (called voxels) in it are weakly specialised. When you teach children to read, you specialise voxels for words.

In the process of learning to read, the task of recognising faces and objects is partially displaced to the right hemisphere. The lack of this displacement is therefore also a marker of dyslexia.

This makes room for the creation of the Visual Word Form Area (VWFA), and the development of a whole new circuit for processing language visually. Learning to read increases the physical connections (myelination) between vision and language in the brain.

The VWFA develops in the same area in the brain, regardless of which language you speak.

Learning music or maths also reorganises your brain. Competition for neurons means that learning music shifts your VWFA slightly. Brain scans of mathematics professors looking at numbers and formulas appear different from scans of the brains of humanities professors on equal salaries looking at the same numbers and formulas.

The process of learning to read then changes the spoken language system.

It’s much harder to learn to read as an adult

The brain area that children typically re-purpose for reading has already been specialised for recognising faces and objects by the non-literate adult brain.

This makes it much harder to learn to read as an adult. We see this in the slow progress of most adult learners. It’s a bit too late for their brains to re-specialise.

It’s also harder to relearn reading if this skill is lost. A colleague of Dehaene’s had a small, specific stroke to the reading area of the brain and lost the ability to read. He was eventually able to relearn in a painstaking, letter-by-letter way, but not able to read fluently.

While neuroplasticity declines gradually over time, puberty is an important moment for the loss of brain plasticity.

Studying les enfants’ learning

France has a national phonics check to make sure children can read 50 simple words by the end of grade 1. This is not controversial.

To study brain area activation in children in Dehaene’s lab, they ask children to pretend to be astronauts going on an adventure in a rocket, and this helps them find going into a scanner to have their brains scanned fun, not scary.

Learning to read is at first very effortful. In their first year of learning to read, children’s brains light up a lot on scans during reading.

In the second year, skills are more automatised so there is lower activation.

Letter reversals

Our brains have a mirror invariance system that allows us to recognise objects as the same, even though they look different from different angles.

We have to override this system when we learn to read, so we can perceive letters like p, q, b and d as different. This is difficult and takes time, which is why children often reverse letters.

Learning the different gestures involved in writing each letter allows us to surmount this problem.

The difference between novice and expert readers

Children need strong oral language in order to learn to read, including strong phonology (speech sounds) and a strong lexicon (vocabulary).

When they start school, teaching needs to focus first on phoneme-grapheme (sound-spelling) mappings, as this is the main route into reading.

These must be explicitly taught, as the concepts involved are very abstract. Children must relate the space of the written word to the time of the spoken word.

At first, graphemes must be consciously processed in a series/one by one.

As the learner’s skills and experience grow, the letters of a word start to be unconsciously processed in parallel/all at the same time.

This frees up the learner’s attentional resources to focus on the meaning of what is being read.

Dehaene says, “Reading is never global or whole word, especially not in children”.

Beginning readers engage in slow, serial decomposition of words, and skilled readers engage in fast, parallel decomposition of words.

This means it’s time to stop asking children to memorise lists of high-frequency words. Research has shown that whole word memorisation doesn’t help to create the brain’s reading circuit.

Attentional focus affects learning

A group of researchers (Yoncheva et al) taught two groups of adults to read an artificial script.

One group was taught to pay attention to the words as wholes (taught in a Whole Word way).

The other group was taught to pay attention to the graphemes and phonemes (sounds and letters) in the words (taught in a phonics way).

Only the group taught using the phonics approach were then found to have left brain activation when reading the script. The whole word group had right brain activation.

The group taught using a phonics approach were able to generalise what they had learnt to allow them to read new words written in the same script. The group taught to pay attention to whole words couldn’t do this.

Think about this. Intelligent adults did not deduce the alphabet from words, yet that’s what young children are often expected to do. Directing attention correctly sends information to the correct brain circuits.

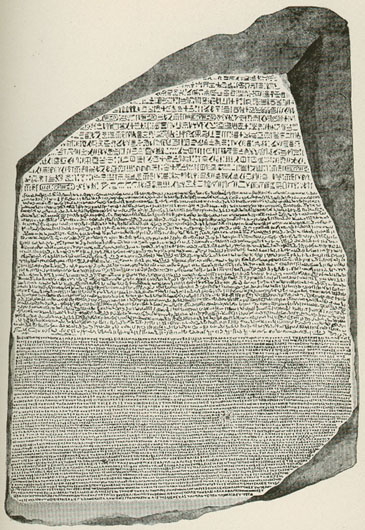

The Rosetta Stone and reading comprehension

Whenever you train phonics you improve comprehension, because reading is a cipher.

Think of the Rosetta Stone. If you can’t decode it, you can’t understand it.

Developing adult-level language comprehension is a long-term process, involving vocabulary enrichment, understanding of complex referents and so on.

Once you can read, this changes your spoken language system. It gives you access to more and different language.

The importance of writing for reading

Our brains have a circuit which specialises for recognising writing gestures. There is a lot of evidence that reading improves when learning to write.

The research is very clear that reading and writing should be taught together. You can learn to type later on.

Daily practice and sleep are also very important for learning.

Want to find out more?

Reading in the Brain by Stanislas Dehaene is published by Penguin Random House. Highly recommended. I have a dog-eared copy, but in a weird, groupie way bought an extra copy I will probably never read for him to sign at the conference.

He also wrote a book called “Apprendre à lire: Des sciences cognitives à la salle de classe“, which my rusty high school French translates as “Learning to read: from cognitive science to the classroom”. I’m looking forward to the (apparently imminent) English translation.

In 2015 I wrote a couple of blog posts about Prof Dehaene’s work, one of which includes a link to a video of him giving a talk. They are here and here.

Shallow and deep phonics

18 Replies

My last blog post copped a little flak for its focus on the Victorian Education Department’s top two pieces of advice for parents when their children are stuck reading a word, both of which start with the sentence, “Look at the picture.” (see p14 of this document).

This is very bad advice because it directs children’s attention away from the key information required for good word-level reading. It’s based on the idea of multi-cueing/the three-cueing system, which is scientifically-debunked nonsense. A complex but excellent explanation of why can be found here, and the actual role of context in reading is explained well here.

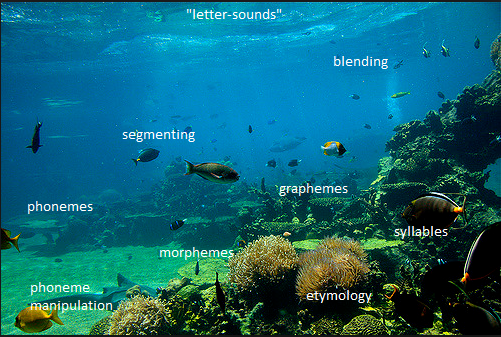

To read an unfamiliar word, children need to take it apart into spellings (graphemes) e.g. “n”, “igh” and “t”, not “ni”, “g” and “ht”, associate these with the relevant speech sounds (phonemes) and blend them into a word. With practice, familiar words are unitised in memory, via a process called orthographic mapping, and no longer need to be sounded out, they become instantly recognised.

Unfamiliar words of more than one syllable must be sounded out a syllable at a time. Earlier syllables must be held in memory while later syllables are worked out, making long words harder.

Once a printed word is converted into a spoken word, its meaning can be accessed, if it’s known. But even if a child doesn’t yet know what a word means (i.e. it’s not yet in their semantic memory), having heard it before (i.e. having it in their phonological memory) kick-starts the process of putting it into long-term memory for instant recognition. Over time the child can learn and refine its meaning(s), and how to use it, by hearing and seeing it in use. (more…)

Decodable texts and lesson-to-text match

11 Replies

A state election looms here in Victoria, and parent-run group Dyslexia Victoria Support (DVS) is petitioning politicians to provide decodable books to all kids starting school in 2019.

Decodable books provide the reading practice for phonics lessons. They include sound-letter relationships and word types learners have been taught, plus usually a few high-frequency words with harder spellings needed to make the book make sense, which are also pre-taught.

Decodable books would replace the widely-used predictable/repetitive texts, which encourage children to guess and memorise words, not sound them out.

At the moment, children might be learning about “i” as in “sit” in phonics lessons, but take home a predictable text that might contain words like “find”, “ski”, “shield”, “bird”, “friend” or “view”. Instead of helping kids practise the sound-letter relationships they’ve been taught, their home readers can undermine this teaching.

DVS’s campaign hit the statewide media this weekend, yay, with an article called “Dull, predictable: the problem with books for prep students” in Fairfax newspapers.