Sounds and letters

5 Replies

If you want to store a large, complex system such as the English spelling system in a finite human brain, you have to organise it well.

To organise something, you first need an organising principle or principles.

If you want to use the relationship between letters and sounds as your organising principle for spelling (and most sensible people do), you can start from the letters and work to the sounds, or start from the sounds and work to the letters.

Starting from the letters

There are 26 letters in the English alphabet, but English also has a whole stack of letter combinations that can represent individual sounds:

- Two letter combinations, like “oo” as in “book”, “er” as in “her”, “ph” as in “phone” and “ey” as in “key”

- Three letter combinations, like “igh” as in “high”, “dge” as in “bridge”, “tch” as in “catch” and “ere” as in “here”.

- Four letter combinations, like “eigh” as in “eight”, “aigh” as in “straight”, “augh” as in “caught”, and “ough” as in “bought”, “drought”, “dough”, “through”, “thorough” (but not “cough” or “tough”, where the “ou” and the “gh” represent different sounds, and just happen to be next to each other).

To add to the complexity, many letters and letter combinations can represent more than one sound, for example, the letter “y” represents four different sounds in the words “yes”, “by”, “baby” and “gym”. The spelling “ea” represents three different sounds in the words “beach”, “dead” and “break”.

As well as more common letter-sound patterns, there are letter-sound patterns that only occur in one or two words, like the “sth” in “asthma” and “isthmus”, and the “xe” in “axe”, “deluxe” and “annexe”.

It's an almost impossible task to use letters and letter patterns to organise your thinking about spelling, as there are simply so many of them and their relationships with sounds are so complex.

After a while it starts to seem that there must be thousands of sounds in English, whereas there are only 44[1] . So let's try using sounds as our organising principle.

Starting from sounds

The sounds of English are:

Three pairs of consonants made by stopping airflow in the mouth then letting it go:

- “p” as in pop, puppy and cantaloupe (voiceless lip sound).

- “b” as in bob, rubber, build and cupboard (voiced lip sound).

- “t” as in tot, butter, backed, joked, laundrette, torte, Thomas, receipt, debt, yacht, indict and pizza (voiceless tongue tip sound).

- “d” as in did, muddy, wagged, aide and jodhpurs (voiced tongue tip sound).

- “k” as in cot, king, luck, quit, chrome, mosque, khaki, liquor, accord, excel, Bourke, trekking, acquaint, racquet and zucchini (voiceless back of the tongue sound).

- “g” as in go, biggest, guide, ghoul and morgue (voiced back of the tongue sound).

Three pairs of consonants made through your nose using your voice:

- “m” as in mum, hammer, limb, autumn, programme and paradigm (lip sound).

- “n” as in non, runner, know, reign, cayenne, pneumonia and mnemonic (tongue tip sound).

- “ng” as in wing, think and tongue (back of the tongue sound).

Four pairs of friction sounds made by squeezing air through narrow spaces in the mouth:

- “th” as in thin, Matthew and phthalates (voiceless tongue-between-teeth sound).

- “th” as in this and breathe (voiced tongue-between-teeth sound).

- “f” as in far, sniff, phone, cough, Chekhov, gaffe, carafe and often[2] (voiceless teeth on lip sound).

- “v” as in vat, love, skivvy, of, Stephen and Louvre (voiced teeth on lip sound).

- “s” as in sell, city, voice, house, scent, pass, whistle, psychologist, quartz, coalesce, mousse, sword, asthma, and waltz.

- “z” as in zip, is, pause, dazzling, bronze, xylophone, dessert, business and tsar/czar.

- “sh” as in ash, lotion, passion, pension, facial, chef, schnitzel, moustache, ocean, sugar, appreciate, initiate, conscience, tissue, cushion, crescendo and fuchsia.

- “zh” as in beige, vision, pleasure, aubergine, déjà vu, seizure, equation and casuarina.

One pair of sounds made by stopping the air and then releasing it through a narrow space in the mouth:

- “ch” (a combination of “t” and “sh”) as in chair, hutch, creature, bocconcini, cappuccino, kitsch, luncheon, question, righteous, ciao and Czech.

- “j” (a combination of “d” and “zh”) as in jar, gem, sponge, ridge, budgie, religion, adjust, suggest, educate, soldier and hajj.

Four semi-vowels:

- “w” as in we, when, quack, one, marijuana and ouija.

- “y” as in yum, onion, hallelujah, tortilla and El Niño.

- “r” as in rip, wrist, barrel, rhubarb, diarrhoea and Warwick.

- “l” as in look, doll, grille, aisle, island and kohl.

One friction sound that has no pair:

- “h”, made by squeezing air through the back of your throat, as in hat, who, jojoba and junta.

So that makes 24 consonant sounds. Then there are 20 vowels:

Six “checked” vowels that require a consonant sound after them in English (sometimes called "short" vowels):

- “a” as in at, plait, salmon, meringue and Fahrenheit.

- “e” as in wet, deaf, any, said, says, friend, haemmorhage, leopard, leisure, bury and Geoff.

- “i” as in in, myth, passage, pretty, breeches, busy, marriage, sieve, women and bream.

- “o” as in on, swan, because, entree, cough, John, lingerie and bureaucracy.

- “u” as in up, front, young, blood, does and laksa.

- “oo” as in pull, good, could, wolf, tour and Worcestershire.

Six other vowels that are sometimes called “long vowels” (they're not really long, but they can be the last sound in a word):

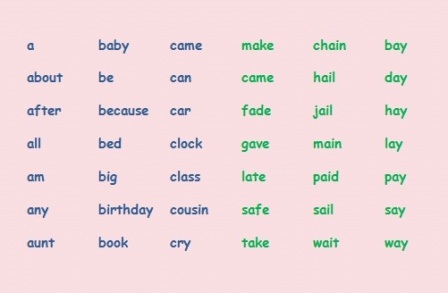

- “ay” as in same, sail, say, danger, weigh, vein, they, café, reggae, great, purée, fete, straight, gauge, gaol, laissez-faire and lingerie.

- “I” as in like, hi, by, pie, high, type, chai, feisty, bye, height, kayak, eye, iron, maestro and naive.

- “oh” as in rope, no, boat, goes, glow, plateau, soul, mauve, though, yolk, brooch, owe, sew and Renault.

- “ooh” as in food, June, chew, brutal, youth, clue, fruit, to, sleuth, shoe, roux, coup, pooh, through, two, manoeuvre and bouillion.

- “you” (a combination of “y” and “ooh”) as in use, few, cue, feud, tulip, beauty, pursuit, ewe and vacuum.

- “ee” as in bee, eat, field, me, these, jelly, taxi, turkey, ceiling, marine, paediatric, amoeba, quay, people, Grand Prix, fjord, ratatouille and Leigh.

Seven other vowels, some of which are called "r-controlled" vowels in some spelling books:

- “ar” as in arm, past, calf, blah, charred, are, baa, clerk, aunt, heart, bazaar and bizarre.

- “er” as in fern, curl, dirt, word, pearl, purr, err, whirred, slurred, masseur, journalist, milieu, were, colonel, myrrh, myrtle and hors d’oeuvre.

- “aw” as in saw, cord, more, court, faun, bought, wart, all, door, chalk, taught, board, dinosaur, baulk, sure, broad, awesome, you’re, corps, extraordinaire, hors d’oeuvre and assurance.

- “ou” as in out, cow, drought, kauri, Maori and miaow.

- “oy” as in boy, soil, Freud, lawyer and Despoja.

- “air” as in care, fair, pear, parent, aerial, solitaire, there, sombrero, heir, their, they’re, prayer, mayor and yeah.

- “ear” as in dear, beer, tier, ere, bacteria, souvenir, Hampshire, weird and Shakespeare.

One unstressed vowel, heard mostly in multisyllable words:

- “uh” as in fire, super, metre, buzzard, tractor, odour, jealous, nature, mynah, violent, pencil, cherub, delicate, granite, purpose, minute, restaurant, aesthetic, martyr, mischievous, borough, portrait, foreign, papier-mache, cupboard, sulphur, porpoise, circuit, tapir…

The unstressed vowel also occurs in spoken sentences in small, grammatical words like "a" and "the". Because these words occur very frequently, this can be a source of much confusion about how basic vowels are spelt.

This is still a long list, but at least it's possible to put a lid on it, by teaching the main spellings for all the sounds in one-syllable words, then the main additional spellings in longer words.

Eventually you find you've got most words covered, and there's just a list of weird ones for each sound that don't follow any major pattern, and are therefore also memorable.

Learners can make up a spelling collection with a page for each sound, and list all the spellings they know in groups. In fact there are books you can buy for this purpose such as Soundasaurus, but I generally quibble with some of the categories, and prefer to use my own Spelling Collection. Crossings-out, sticky notes and/or extra pages added in later are good evidence that learners have been actively thinking and learning about the relationship between sounds and letters.

[1] Linguists will always argue about how many sounds there are in English, because the mouth is a mushy place without clear boundaries – for example, the “l” sound at the start of “look” is phonetically different from the one at the end of “hall”, and the sound “ay” in “play” and “ie” as in “time” are technically two sounds, but slicing things that finely doesn’t really help with learning spelling. Most people say there are between 42 and 44 sounds for the purposes of teaching spelling (depending on whether you call "ear" and "air" separate spellings or not).

[2] and lieutenant if you speak British English, but actually this word comes from French and means someone standing in (in lieu) for the tenant or office-holder, so the American pronunciation (“loo-tenant”, not “leff-tenant”) is closer to the original French.

Interesting!

Do you notice a difference in outcomes for synthetic phonics programs that teach letters to sounds and those that teach sounds to letters? What is the norm in available programs?

I wonder if there is a difference in reading vs spelling outcomes. Would learning letters to sounds make it easier to read initially but more difficult to spell correctly (seeing that the spelling process is sounds to letters based)?

Hi Aimee, being a Speech Pathologist, and having always worked on the educational principle that you ho from the known to the unknown, I think it makes more sense to start from children’s speech and help them “hear” the individual sounds in it and map letters onto them, but of course this should always be done in a reversible way, as in the beginning, reading is seeing the letters and mapping the sounds onto them then blending them into words, and spelling is segmenting words into sounds and mapping the letters onto them.

I like to work on spelling as much as possible, because when you spell you read (two for one!), but when you read you don’t spell. Also, parents and teachers are often very focussed on reading but not as much on spelling, and so lots of learners have reasonable reading but weak spelling (and this undermines their reading accuracy). I’ve seen children whose reading was weak suddenly really move ahead after doing some very focussed work on spelling. Spelling is the more exacting skill, requiring recall not just recognition, so you get more phonemic awareness and decoding bang for your buck by working on it – see the great blog post on spelling research at http://www.adihome.org/adi-blog/entry/feel-like-a-spell.

Genius!

Much appreciated!!

There are technically more than 44 sounds in the English language – each consonant is at least three:

E.g the ‘b’ is different in lube (>b), but (b*), and rubber (>b*)

E.g the ‘L’ is different in knoll (>L), lite (L*), and rolling (>L*)

E.g the ‘s’ is different in shares (>s), sit (s*), and possible (>s*)

I have long wondered if there is a way to describe these. I made up >* notation. Perhaps you know what it’s really called. :).

Yes, there are many allophones which we mentally catalogue as the same phoneme. In simple terms, a phoneme is a concept in your head, and an allophone is how it comes out of your mouth. Think of the three /t/ sounds in the word ‘titillate’, they are very different in production, but because they are all voiceless alveolar stops (the first aspirated, the second with some voicing carried over from the surrounding vowels, so it sounds a bit like /d/, and the final /t/ often not aspirated) we call them the same phoneme. There is a huge difference between initial and final /l/ but since both are produced with tongue on alveolar ridge and the sides of the tongue lax, we think of them as the same phoneme. There’s a lot on the internet about allophones, and a notation system for them all in the International Phonetic Alphabet, but in general, all phonemes are affected by the sounds around them (coarticulation) so they are all pronounced multiple ways. Hope that makes sense. Alison