“Can I halp you?” The Salary-Celery merger

0 RepliesIf you’re in south-eastern Australia or New Zealand, you’ve probably noticed kids pronouncing words with /e/ (as in ‘egg’) more like /a/ (as in ‘at’) before the sound /l/.

They say things like ‘Can I halp you?’, ‘I falt a bit sick’ and ‘I can do it mysalf’. They pronounce ‘salary’ and ‘celery’ as homophones, hence the name linguists have given this vowel shift: the Salary-Celery merger.

The ‘a’ before /l/ in ‘asphalt’ was being pronounced /e/ when I was scraping my knees on it at school, but ‘a’ pronounced /e/ mainly occurs before /n/, as in ‘any’, ‘many’, ‘secondary’ and ‘dromedary’.

Several other vowels have also morphed a bit before /l/, consider:

- all, ball, call, fall, gall, hall, mall, also, almost, always etc (but not ‘shall’, ‘ally’, ‘alley’, ‘ballad’, ‘gallop’, ‘pallet’, ‘tally’ or ‘alas’).

- walk, talk, chalk, stalk, and baulk (US balk) and caulk (US calk).

- half/halve, calf/calve, behalf (but not ‘salve’ or ‘valve’).

- salt, halt, malt, gestalt, alter, exalt, Walter (but not ‘shalt’).

- fault, vault, cauldron, assault, cauliflower, hydraulic, somersault (but not ‘haul’ or ‘maul’).

The sound /l/ has a vowel-like quality and tends to ‘colour’ the preceding vowel. This is useful for teachers to know, so they can give any confused kids plenty of practice spelling affected words (there’s lots of opportunities to practice writing ‘short vowels’ in a range of phonetic contexts, including before /l/, in Spelfabet Workbook 1)

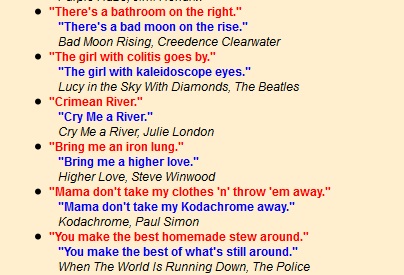

When kids insist that they hear an /a/ (as in ‘cat’) in ‘halp’, I ask them to say the word in their ‘spelling voice’ (as it’s written), with /e/ (as in ‘red’). Good spellers often say that they pronounce odd spellings a bit weirdly when writing them (Wed-nes-day, bus-i-ness), as a kind of mnemonic. Spelling pronunciations sometimes crop up in comedy too, for example the kniggits in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

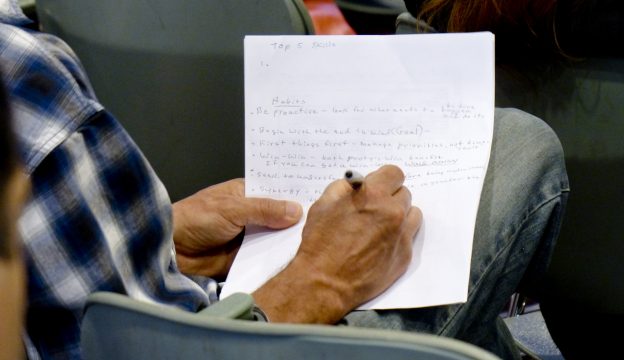

US reading/spelling guru Professor Linnea Ehri was recently here in Melbourne courtesy of Learning Difficulties Australia (the selfie at right proves we met her), and talked about this strategy, which she calls the “Spelling Pronunciation Strategy”. She says that in Connectionist theory, to put a word’s spelling into long-term memory, the letters must be connected to ‘phoneme mates’ in the pronunciations of the word.

To use the Spelling Pronunciation Strategy (AKA “Spelling Voice” in the program Sounds-Write) you separate and say each syllable with stress, and pronounce all the letters. Prof Ehri’s examples were “ex cell ent ”, “lis ten”, “choc o late”, and “Feb ru ary”. She cited two studies (Drake & Ehri, 1984 and Ocal & Ehri, 2017) showing that assigning spelling pronunciations enhanced memory for spellings, in 4th graders and college students.

So in summary, it’s not just harmless to say words in a slightly funny way to halp, sorry, help yourself remember their spellings. It’s officially evidence-based.

Low frequency word spelling test

9 Replies

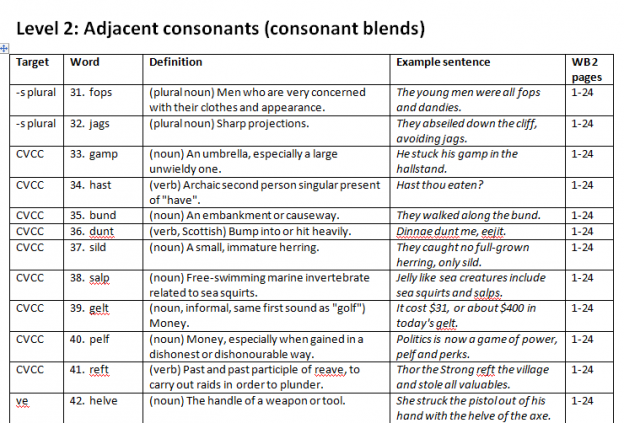

I’ve just made up a free, low-frequency word spelling test which you can download here and use to explore learners’ spelling skills and knowledge.

It’s not a standardised test, so won’t tell you whether a learner’s spelling skills are behind, on a par with or ahead of peers. Its purpose is to focus your attention on the things that matter most for spelling:

- speech sounds (phonemes),

- letter patterns that represent these sounds (graphemes),

- word structure (positions and combinations of sounds in words/syllables),

- parts of speech e.g. “pact” is a noun, “packed” is a verb,

- meaning (especially for homophones like see/sea),

- meaningful word parts (morphemes such as prefixes, suffixes and word stems/roots).

This should help you work out which key skills and knowledge learners already have, and which they need to learn, and thus help teach them to spell explicitly, systematically and effectively.

Don’t do the whole test with anyone, it’s far too long (390 items). Start at your learner’s estimated current skill level, and work forwards if they get words mostly correct, and backwards if they don’t. Stop when you hit a floor (most words too easy) or ceiling (most words too hard). (more…)

What kind of knowledge is needed for good spelling?

4 Replies

A lot has been written by philosophers and in Dilbert cartoons about different types of knowledge.

Often these are described using terms like “explicit” versus “tacit” or “declarative” versus “procedural” knowledge. What matters most for spelling?

Declarative versus procedural knowledge

Explicit, declarative knowledge is theoretical information about a subject e.g. that we use a base 10 number system, and that our Solar System has 8 planets (sorry, Pluto). Libraries, databases and the internet are full of it.

Procedural knowledge is often harder to describe (more tacit) and more practical. It’s knowing how to do something, like tie up a shoelace, play the guitar or ride a bike.

I have quite a bit of explicit, declarative knowledge about how to play brilliant tennis (yes, the Australian Open men’s final is on, but we love both Roger and Raffa, so who to barrack for?!) but despite years of trying (our tiny country town didn’t have enough kids to field a team without unco asthmatic me), I never managed to convert this into much procedural knowledge.

I’ve been nerdily immersed in spelling books lately, and have realised that most books about spelling are full of explicit, declarative knowledge, but aren’t necessarily much help with the “how”, or what we should be doing to build tacit, procedural knowledge of spelling. (more…)

Helping children hear sound differences

3 Replies

Children starting school often have immature articulation, and still can't get their little mouths around sounds like "z", "r", "v" and "th". Many children still can't produce the difference between "fin" and "thin" or "vat" and "that" at age eight or even later.

However, children typically have to deal with the letters/spellings representing these sounds in their first year of school. The classic example is the word "the", one of the first written words children are expected to read, though few 5-year-olds can actually say "th".

Teachers and parents often refer children to Speech Pathologists because, "He says 'I fink' and writes it with an F" or "She says 'a wabbit' and writes W". If children are not aware of the existence of the separate sounds "th" and "r", they're just being logical, but that's not going to help them spell these words right.

Children often "collapse" two similar sounds into a single category, such as "s" and "th", and hear word pairs like "sink-think", "sick-thick" and "sore-thaw" as homophones (the latter if you speak Australian/UK English, but not American English).

You can help make children aware of the difference between sounds they mix up, and thus make more sense of how they are spelt, by showing them words which contrast these sounds, while keeping the rest of the word the same, and getting them to listen carefully for the difference between the words.

Minimal pair pictures

These are called "minimal pairs", for example "choose" and "shoes" sound the same except one has "ch" at the start, and one has "sh".

There are whole sets of minimal pair pictures on the internet, but it can be hard to find the key contrasts that typically confuse kids who are just talking like typical four to seven-year-olds.

Australian Speech Pathologist Caroline Bowen has an amazing website where she very generously makes minimal pair pictures freely available, though she asks for a donation towards site upkeep and bandwidth if possible. Now that I understand the time and money it takes to keep a website going, I urge you to donate if you can (I've done so now, but should have long ago).

Here are the links to Caroline's pages of minimal pair pictures for some of the late-developing consonant sounds that often worry parents and teachers.

I cannot emphasise too much that if you're not sure whether a child has an articulation delay (not just a speech error typical of her or his age), please consult a Speech Pathologist, especially if the child is sometimes hard to understand. Children who can't say sounds like "k", "g" or "f" at school entry need speech therapy.

While many young children may not be able to say some of these sounds, just being aware they're different when starting to read and spell them can help make more sense of their spellings. And being aware of them is the first step on the path to being able to say them.

- "sh" versus "s" as in sheet/seat – word beginnings and ends

- "sh" versus "ch" as in ship/chip – word beginnings and ends.

- "s" versus "th" as in sink/think – word beginnings.

- "f" versus "th" as in fin/thin – word beginnings and ends.

- "w" versus "r" as in wok/rock – word beginnings (Australian English doesn't put "r" at word endings)

- "w" versus "l" as in wait-late – word beginnings (we also don't say "w" at word endings).

Note that by their fifth birthday most children should have nailed "sh" and "ch", please refer them to a Speech Pathologist if not. I've included these sounds because some children start school at age four, and some preschoolers demand to be taught to read and spell before they start school.

Note also that the pictures use Aussie English vocabulary, e.g. a thong is an item of clothing you wear on your foot. Any pictures that you don't think are relevant (wherever you are) can be left out of whatever listen-for-the-difference game you decide to play with them. The three pictures in this blog post are all from Caroline Bowen's minimal pair pictures.

I hope this helps you explain to small people why the words "think" and "sink" are written differently even though they sound the same. The answer is: they don't. And that's often news to small people.

What is poor phonemic awareness?

1 Replies

Many, perhaps most, struggling readers and spellers have problems discerning the identity, order and/or number of sounds in spoken words.

Assessment reports often call this poor phonemic awareness, or sometimes poor phonological awareness.

"Phonemic" is talking about individual sounds. "Phonological" is a more general term including syllables and rhyme.

Sound identity

The mouth is a small, mushy, fast-moving place, and a lot of the sounds it makes are very similar.

The sounds "k" and "t" are easily confused because they're both made by stopping airflow with the tongue on the roof of the mouth, then letting it go with a little airburst.

Have a go spelling

13 Replies

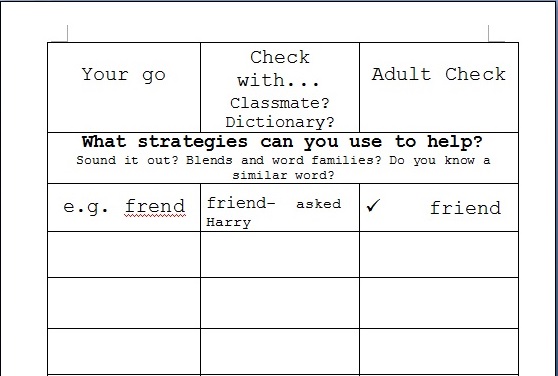

In class, many of the students I work with are encouraged to "have a go" at spelling words that they aren't sure how to spell.

Often this happens when they have spelt a word incorrectly in their first draft of a piece of written work.

The teacher then points out the error, but doesn't correct it.

Instead, the student is encouraged to problem-solve the spelling, by asking classmates, trying to sound it out, thinking about word families or similar words, or looking it up in a dictionary.

If you google "have a go spelling", you can even find a free workbook for this purpose. The front of it looks like this (the fonts are a bit out of whack because I don't have the SA school font, but it is an MS Word document so this could be easily fixed):

The remaining pages have three columns: one for the word as misspelt, one for the student's "go" and one for the correct spelling as checked by an adult.

a and u vowel contrasts

4 Replies

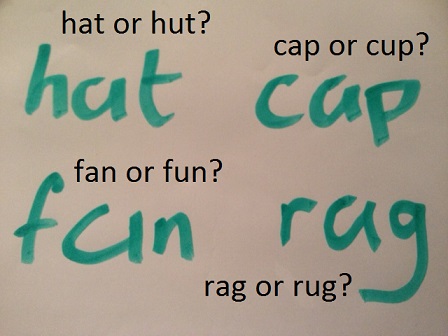

Today at school I was working with some students who persistently confuse the vowel sounds "a" as in "cat" and "u" as in "cut".

Not being sure of the difference, they often write a letter that's like a cross between "a" and "u", an "a" with the top down. Which is a clever, 2-bob-each-way strategy, but when typing there is no such letter, so they need to iron the difference between these two sounds and letters out.

Lots of learners confuse these sounds/letters, partly because one of the first words most children are taught to read is the indefinite article "a", as in "a book" and "a cat".

Teachers and parents usually pronounce this word like "u" as in "cup", though it would be a lot less confusing for beginners if they used the stressed pronunciation "ay" for this word (see this previous blog post for more).

Once kids have learnt to say "u" when they see the letter "a", they are logically inclined to read "bat" as "but" and "fun" and "fan".

Can't blame them for that, especially if they are also meeting lots of other words with an unstressed "a", like "ago", "across", "sofa" and "umbrella".