Grouping by ability

0 Replies

One of the schools I'm working in at present has a Grade 2 class with a number of slow progress readers/spellers who've been referred to me for therapy.

I did my usual assessments to check their phonemic awareness and decoding skills – the Lindamood Auditory Conceptualisation Test and the Martin and Pratt Nonword Reading Test – and all these children were well behind the level expected in Grade 2. A couple of them had the kind of skills ordinarily expected of children in their first year of school, although they're now in their third year.

There are also a couple of children with articulation errors in the same class, and since wobbly sounds often go with literacy difficulties, I did a quick Martin and Pratt Nonword Reading test with one of them the other day, only to discover that he has the reading word attack usually expected of a sixteen-year-old.

How do you teach a class with a ten-year reading skill gap?

How is this Grade 2 teacher supposed to teach reading and spelling in any meaningful and coherent way, when the most capable reader in the class is ten years (whatever that means, when he's not even ten) ahead of the weakest reader, while the weakest readers started out the year barely able to read anything? (though I'm happy to report most of them have now polished off the first 20 Little Learners Love Literacy books).

How did we get into a situation where a teacher is even asked to attempt this?

Some variation in ability levels is expected in any class, but such a huge gap makes the teacher's task nigh impossible – teaching materials suitable for one end of the spectrum are completely unsuitable for the other end, and the kids in the middle need something (or perhaps several things) different again.

Multi-age groups are efficient

I've been grouping learners with similar skill levels from different classes for work on synthetic phonics, but there are a couple of students in Grades 4, 5 and 6 whose spelling skills in particular are very weak.

I've thought about grouping these much older students with much younger ones with similar ability levels. Like all Speech Pathologists in schools, I'm pressed for time, and this would be an efficient way to work.

Our cultural beliefs about a skill affect how we can teach it

However, it's not generally acceptable to group learners by ability level to teach reading and spelling in the Australian school system. I'd seriously wound the pride of someone in Grade 5 if I asked him or her to work with Grade 1 or 2 students.

In Australia, reading and spelling are widely and incorrectly viewed as natural developmental skills, not complex, artificial skills.

Our complex system for writing down language is no more natural than the internal combustion engine. Both are human inventions, but now both have become so culturally ubiquitous that we are almost too close to them to see them properly any more (though I was happy for the planet to hear that Gen Z is more inclined to think of the car as an expensive mobility appliance you have to stop social networking to operate than a status symbol).

If we had to teach 30 primary-school-aged how to ice-skate, we'd first figure out what they could do, then group them by ability and pitch our teaching to their different skill levels. It would seem ludicrous to insist on teaching all the Grade 6s together if some of them could barely stand up on skates while some could skate backwards.

However, nobody thinks that the subtext of saying a child in Grade 6 can't ice-skate is that the child is probably not very bright.

A temporary teaching problem or a permanent learner problem?

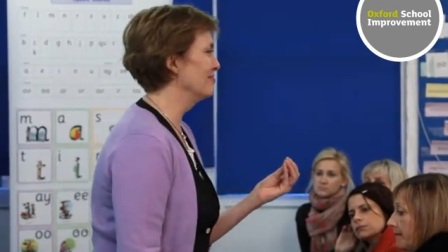

While dredging YouTube for training videos to add to my Phonics Resources lists, I came across a video from UK synthetic phonics expert Ruth Miskin, which recommends that we "group all the children across the school in terms of their reading ability, so they can be taught at their own level every day. The more homogenous the group, the more focussed the teaching, and the faster the progress of the children."

This willingness to group children by ability regardless of age seems to reflect a major philosophical/attitudinal difference – Miskin's approach is underpinned by confidence that the teaching will be effective, all the children will make fast progress, and the muti-age groupings will only be temporary.

She sees the problem primarily as a teaching problem, not one that resides in the learner.

In the Australian system, we don't have this confidence, as large numbers of Australian children still finish primary school without being able to read and write well, and we tend to attribute this problem to the learners, not how they're taught.

If all children were taught the basic building blocks of our written language right from the start, I'm convinced we wouldn't have such huge disparities in literacy skill levels in our classrooms. Right now, some kids are able to crack our spelling code quickly, but many are left wondering well into their third or even fourth year of schooling, thanks to "wait and see if he/she grows out of it" thinking.

Anyway, here's the video from Ruth Miskin, I'd be interested to hear what you think of it.

Leave a Reply