How the brain learns to read

6 Replies

I’ve just found a great 20-minute talk on YouTube by Stanislas Dehaene, a French cognitive neuroscientist, called “How the brain learns to read”. He wrote a classic book called “Reading in the Brain” that I occasionally reread bits of when I want to feel wholly inadequate.

“Neuro” language is often used to make questionable or worse programs and products seem more scientific and impressive, but the things Dehaene says in this video are straightforward and consistent with the classroom research on how to teach literacy fast and well. So I hope his pictures of brains don’t put anyone off, he’s not selling anything or trying to get anyone to suspend their critical faculties.

I’ll embed the link to the video here, and then summarise his main points below.

Reading starts in the back of the brain and quickly moves to the area responsible for recognising letters, then to the areas concerned with meaning and pronunciation. These latter two areas are already in working order because children know how to speak and listen, so the task of learning to read involves connecting up the visual system to the language system.

Learning to read changes the brain. The area responsible for recognising letters only activates in literate people when they look at print (in their own language), not those who haven’t learnt to read. It activates in direct proportion to the person’s reading ability.

There are also changes in the visual cortex and the area responsible for processing the sounds (phonemes) of speech, because learning to read is to a large extent the capacity to attend to the individual phonemes of speech and to attribute them to letters. The fibres connecting these areas involved also change.

In those who can’t read, the letter recognition area is used for face recognition. In the process of learning to read, some of this function is displaced to the right hemisphere of the brain.

“Mirror reading” and “mirror writing” reflect a symmetry mechanism in this part of the brain which allows us to recognise faces and objects from any angle. When we learn to read and write, we have to un-learn this in relation to letters.

Phonics is superior to whole word training. As adults we have forgotten how we learnt to read, and we imagine we read whole words/shapes without attention to individual letters. But if we look at what is going on in the brain, the brain is still processing every letter. Dehaene says, “Whole word reading is a myth…the brain does not use the whole word shape”. Skilled readers are processing letters simultaneously, whereas children need to work slowly, one letter at a time, till they gradually get faster and more automatic.

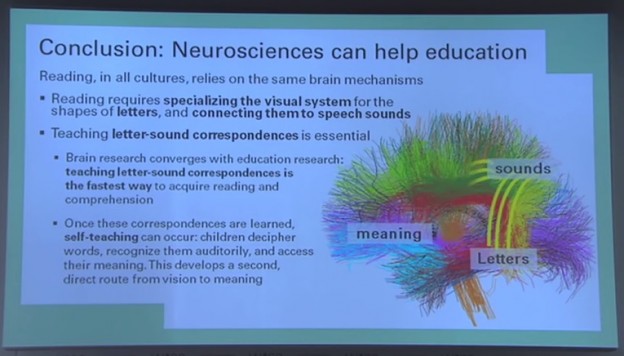

In all languages, reading requires specialising the visual system for the shape of letters and connecting them to speech sounds, even in Chinese. Teaching the correspondences between sounds and letters is essential, and is the fastest way to acquire reading and comprehension. Once the correspondences are learnt, children can get on with self-teaching through independent reading. This develops a second, direct link between the visual and meaning areas. All current models of reading involve two routes.

Some colleagues in Finland have developed a game called Graphogame, and shown that just a few hours of training with this game is enough for preschoolers to begin to develop visual word form systems (2018 update: but please note this new research which does not support its use). Dehaene’s lab has also made free online software to teach number and basic arithmetic called The Number Catcher.

We are all primates and we all have cognitive constraints, and teachers need to understand these to teach well.

The last 14 minutes of the video are questions to which Dehaene gave the following answers:

- When illiterate adults learn to read, their brains change in much the same ways as in children, but maybe a bit slower. It is possible to learn to read at any age.

- There are no drugs that are known to help with learning, but rewards can help, and giving children more sleep is another way to help them learn, especially in cases of attention disorders.

- The connection system in the brain may be abnormal in dyslexia, though the problems created can be compensated for.

- Cursive writing is good for the brain. It adds another circuit in the brain to do with recognising the gestures of writing, and thus helps children to learn to read. Perhaps it helps them write in the right direction and break the symmetry, a letter P looks very different from a Q in cursive. Drawing activities and learning about phonics in preschool also help children to learn to read.

- Brain mechanisms for reading are the same around the world and good predictors of learning to read include phonics and vocabulary, in all languages. Parents from low socioeconomic families sometimes need to be told to have conversations with their children, to enhance their vocabulary and understanding of speech sounds, and thus help their literacy.

- When designing games it is important to get children to attend to the letters and their corresponding sounds, not whole words. It’s also important to minimise distractions so that children can focus on the key information.

- Motivation is an important multiplier of learning, along with attention, concentration and reward.

- There is not much evidence that there is a critical age for learning to read, or an age that is too early. We don’t know what the optimal age is for learning to read, but young children need to be active, moving, creating, so maybe reading can wait till age 6 or 7. Switzerland teaches children to read later, and this seems to be fine.

- English is probably the world’s worst alphabetic language. In languages with very simple spelling systems like Italian, research shows that children can learn in three months, and typically it takes a year to teach children to read in regular languages. In English, it takes two extra years, but should be accomplished after three years. We don’t know exactly what is happening in bilinguals but the same brain areas are used and once you’ve learnt one language, you can learn a second one faster.

Thanks Alison, I found myself cheering!

[…] How the brain learns to read | Spelfabet. […]

Absolutely brilliant reinforcement of the facts.

Thank you!

[…] in Perth in April) gives a nice video explanation of how the brain actually learns to read here, and David Kilpatrick unpacks the psychological and educational research on this […]

[…] Prof Dehaene’s work, one of which includes a link to a video of him giving a talk. They are here and […]

[…] skills (See this Thinking Reading blog post and/or Mark Seidenberg’s book and/or the work of Stansilas Dehaene for more). So I was surprised by Clark’s e-book Goodman et al […]