The Great Australian Spelling Bee

5 Replies

There was an interesting interview on Radio National about spelling today, inspired by new TV quiz sensation the Great Australian Spelling Bee.

In the GASB (as I’m sure we’ll all soon be calling it), children aged 8 to 13 start off spelling words like “lousy”, “voyage”, “kelpie” and “gravel”, which get progressively harder, till the live audience goes mad ape bonkers at their brilliance, they can spell cretaceous! OMG.

GASB has tension-building music, a “Spelling Gate”, timers, a leader-board, Challenges, a Pronouncer/Judge who leaves long, hold-your-breath pauses before intoning “CORRECT” or “INCORRECT”, dinosaurs, tasers, hugging, tears, you name it, and of course lots of interviews with adorable, clever children with butterflies in their tummies, who while being fiercely competitive wish each other the best of luck and want to be friends forever. Everyone simply loves it.

I’ve only been able to watch it from between my fingers, because I find game shows excruciating (sadly I’m more of a Radio National type), and because I suspect the extreme excitement about children being able to spell might be partly because children, or people generally, who can spell really well are the exception, not the rule. It’s (IMHO) unarguably the most undervalued and poorly taught key skill on the curriculum, and has been for a long time.

Now, I don’t want people like my mother (who used to ask her daughters to spell words like “onomatopoeia” and “phlegm”) put in charge of the curriculum, but spelling needs to be taken more seriously and taught less randomly. This is apparently what the new National Curriculum will achieve, huzzah to that I say.

How do people become good spellers?

One of the academics interviewed on the radio this morning said that the children on the GASB show:

- Have a highly specific linguistic skill,

- Have probably done a lot of reading and writing,

- Have probably been exposed to lots of words through speaking and listening.

These are undoubtedly all true, but I was pretty astonished that she didn’t say upfront that they must be very good at pulling words apart into syllables and sounds, and learning the spelling patterns that represent these sounds, and that they were probably taught well. Which I bet most or all of them were, by someone.

What’s the best way to teach spelling?

The academic went on to say that high-achieving spellers have heightened sensitivity to letter patterns, as well as flexible thinking about word meaning and function (e.g. “past” versus “passed”).

She said, “if children are aware and they are explicitly taught about these particular strategies and skills that are involved in spelling, they can build this repertoire of strategies that they can pick and choose from depending on the words they’re spelling. But if they’re put under pressure in a test situation where they’re asked to spell lists of words in a meaningless way, and they don’t have those tools to be able to draw on, they can so easily become frustrated and I feel that their self-esteem might become eroded over time if they constantly seem to fail in these Friday spelling tests that happen so often in many classroom contexts”.

True, especially when the spelling lists don’t make any meaningful point about spelling (see this 2012 blog post). However, she didn’t expand on the explicit teaching strategies teachers should be using, though thankfully there was a consensus among the speakers that spelling is a linguistic activity, not a memory one.

Activities like getting a child to write the same word out multiple times with different coloured pencils also came under fire. Yes, this is pretty pointless, and still happens. Another not-favourite I’ve seen recently is a student being asked to write the first two letters of spelling list words, then the first three letters, then the first four letters, and so on. I’d keep a collection of pointless spelling tasks provided by (no doubt) well-meaning teachers if the idea didn’t make me feel like smashing the crockery.

We were told by the interviewed experts that to learn spelling, children need print exposure, an eye for detail and attention to letter patterns. But nobody more than briefly mentioned sounds, or explained how our spelling system works (click here for an earlier blog post or video about this).

Teachers aren’t usually taught how to teach spelling well

It’s not teachers’ fault they don’t usually know how to teach spelling well. We now have a whole generation of teachers who weren’t taught to spell well at school themselves, because they were educated via the Whole Language literacy-teaching approach. See this earlier blog post about recent research into undergraduate teachers’ spelling skills.

At university, teachers have usually been taught that what’s most important about written language is MEANING. Teaching about language STRUCTURE (sounds, spellings, word parts, grammar) directly and explicitly seems to be positioned as meaningless, boring, and a largely unnecessary, since children can joyfully discover such stuff for themselves through the process of reading and writing interesting, meaningful texts. Or if that doesn’t work, use a spellcheck.

One of the academics on the radio this morning kept emphasising the importance of meaning, and downplayed the importance of sounds for spelling. She said a child on GASB had spelt “cynicism” INCORRECTly as “sinnism” (really? A champion speller left a syllable out? I doubt it but I can’t find this word in the episodes online) because he relied on sounds rather than word meaning.

Well, yes, a child can only spell the word “cynicism” CORRECTly if their spoken language system knows “cynic” or at least “cynical”, and knows how to use and spell the suffix “ism” in words like “criticism” and “activism”. But before they can learn words like these, they need to learn a whole lot of other much more fundamental stuff.

She also said reading a lot helps spelling because it builds your vocabulary and you’ve seen a lot of words, so you know more word meanings and “you’ll be able to visually check it once you’ve written it down”. Too bad if your lack of phonemic awareness and graphemic knowledge means you can’t write anything that looks remotely correct.

The importance of Phonemic Awareness

Long before children even hear the word “cynicism”, let alone read or spell it, they need to be able to discriminate individual sounds in words. That is, they need an EAR for detail. This is not a natural skill, and should be actively taught, to make sure everyone gets it.

I’ve met too many older children, and even a couple of teenagers, who haven’t been aware that spoken words are made of sounds, and letters are how we write them. Maybe this was taught while they were fiddling with their shoelaces, but it’s really not good enough. No phonemic awareness means staying on the reading and spelling dark. Phonemic awareness is like turning the lights on, absolutely necessary, but not sufficient.

As soon as kids can pull words apart into sounds (segment them) they need to start mapping letters/spellings onto them. Once they know one-letter spellings, they need to learn that a sound can also be spelt with two, three or four letters, that most sounds have several spellings, and some sounds share spellings. When reading, this allows us to write words that sound the same differently, and thus not mix up things like blood veins, vain people and weather vanes.

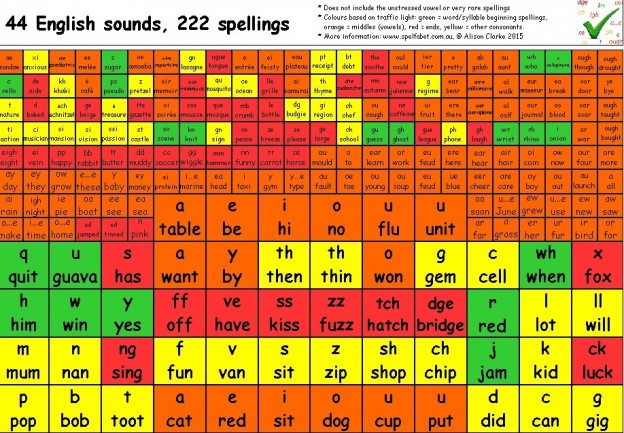

Here’s a little chart showing 222 spellings I made up this morning as a snapshot of our main sound-letter correspondences. If you’re a parent, teacher or otherwise connected with a primary school, please think about how systematically and explicitly your school teaches these spelling patterns. Once a child knows the main patterns, the really tricky spellings (in just one or two words, and not on this chart) are much easier to spot and learn.

Teaching graphemes systematically

If you want a child to spell well, teach them the spelling patterns of our language systematically, first in short words with the simple, common spellings at the bottom of the chart above, and gradually making words longer and more complex.

Once they have the basics, it’s a good idea to teach spellings of a given sound in groups e.g. the different ways we spell “ay”, as in make, main, say, grey, eight, paper, vein, great, fete, gauge, straight, though of course younger children can only manage a few at a time. That way children get an overall picture of how each sound is spelt, which letters tend to go together, which spellings are usually at syllable endings, how base words and suffixes (e.g. act-action, music-musician) work etc. You don’t need complicated spelling rules, just eyeball your lists together and ask questions that direct their attention to relevant information.

Most sounds have two or three major spelling patterns, plus patterns used in smaller groups of words. Sorting words into a spelling collection (my shop has one, or you can make your own) by sound and spelling pattern, then sending kids home on a treasure hunt to find more words with the pattern under study, are two ways to motivate kids to study spelling lists. Just don’t tell them about my free online spelling lists, or free downloadable spelling lookup booklet, so they don’t cheat.

Once a child has a grasp of the main patterns, print exposure locks down which words contain which spellings. Immersing children in the chaos of written English expecting them to be able to identify and master the 200+ main spelling patterns for themselves is no recipe for winning big spelling on TV.

Teaching word parts systematically

Systematic teaching about spelling should include lessons on the way meaningful parts of words (morphemes) have special spellings. For instance, the plural “s” can sound like “s” or “z” depending on whether it follows a voiced sound (the “t” in “cats” is not voiced, but the “g” in “dogs” is). The same thing happens with the past tense “ed” in “jumped” (sounds like “t”) and “banned” (sounds like “d”).

The suffix “ment” which on Channel 10 is added to words like “amaze”, “excite” and “entertain” is pronounced with an unstressed vowel, but consistently spelt with a letter E. So kids need to learn to say that syllable to rhyme with “rent” when they pull words apart into syllables and say them in their “spelling voice” (speak like the Queen, or someone from Trak or the Naw Shaw).

Typically-developing children already know how to make spoken words like “amazeballs” and “selfie” out of word parts, because their brains are wired to learn language. That’s why kids say “I runned” and “I’m versing you” even though adults don’t say such things to them (though apparently they’ve done it for so long that “verse” is now officially a verb). They take words apart and put them back together from an early age, so at school they just need to be taught how to spell the parts.

The importance of etymology (not)

One academic on the radio this morning said teaching about word origins (etymology) is important for spelling, and emphasised children’s “joyous exploration” of things like the impact of kings’ and millionaires’ whims on our spelling. However, she didn’t cite any evidence that teaching about etymology improves spelling, and as far as I know (mainly from discussions on the SpellTalk listserve), there is none.

Etymology is the penguins on top of the spelling iceberg, making it a bit more entertaining, but not part of core business. The iceberg itself is principally composed of sounds (phonemes), spellings (graphemes) and word parts (morphemes).

The etymology-enthused academic explained that the word “chrysanthemum” is made up of the Greek “chrys” meaning “golden” and “anthemum” meaning “flower”. I’m not persuaded that knowing this helps anyone learn how to spell “chrysanthemum” unless they speak Greek, or know it’s a Greek word and that Greek words often spell the sound “k” with CH (as in “school”) and the sound “i” with Y (as in “gym”). But this useful information about sounds and spelling patterns wasn’t mentioned.

Nitpickers, spellcheckers and spelling reform

One of the academics interviewed said that despite being a linguist, she’s not a good speller, but that’s because she’s more of a big picture person not a details person. No mention of instruction, but my guess would be that she went to a Whole Language school, and that spelling instruction (or lack thereof) has much more to do with her spelling skills than her personal style.

She also said that spellcheckers are not always available, and that you need a basic idea about spelling before you can use one (actually you need to be fairly good), so we shouldn’t give up on spelling “completely”.

As you can imagine, I wasn’t warming to her theme that spelling is for pedants and not terribly important, but she did give the thumbs-down to spelling reform, saying it’s not feasible and not usually very effective. She cited recent German spelling reform which has given the word for ship’s captain (something like schiff + fahrer = schifffahrer) a triple-f, discombobulating many. I confess I may be a little bit German in that I’ve always thought there is a “t” missing in “eighth”. But see my 2012 blog post about why she’s right.

Two very interesting developments

The new national curriculum is one interesting recent development in spelling.

The Great Australian Spelling Bee is another.

I bet the Great Australian Spelling Bee does more to revive interest in learning to spell well than anything in the national curriculum.

Hi, I downloaded this spelling guide this morning but it won't let me print it, comes up with a message saying it cannot be printed?

I’m so sorry, I’ll see if I can work out what the problem is

This is just brilliant. My daughter is about to go to school next year (prep) and my husband is a high school English teacher. I’m going to get them BOTH across this article haha! Thanks so much!

Unbelievable that you’ll have a Big Schoolgirl next year! Tell Rob I will be giving him a spelling quiz when I see him next

Hi!

You have done an awesome job. I'm gonna show this to my colleagues who will be so thrilled that teaching is made so easy for them.