The definition of decoding (or “glamping with David Hornsby”)

11 Replies

Last May, educational consultant David Hornsby spoke at Sydney University about “The Role of Phonics in Learning to be Literate”, and his talk was recorded and put on YouTube.

I recently heard from the Developmental Disorders of Language and Literacy Network that the video was being shared widely by teachers on social media. So I took a look.

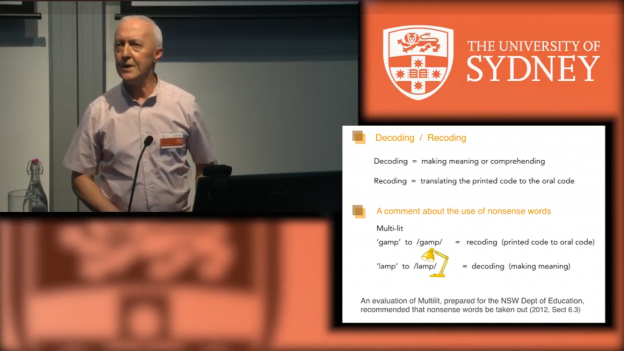

Mr Hornsby begins by explaining that his definition of decoding is “making meaning or comprehending”. Here’s his slide saying this, in case you think I made it up:

In the solidly-evidence-based Simple View of Reading, the term “decoding” usually means word identification, whether this is achieved by sounding out words, or instantly and without conscious effort, once a familiar word’s spelling, pronunciation and meaning are bonded in memory (via orthographic mapping, or in dual route models, via the lexical route).

Sometimes researchers use “decoding” to mean only sounding out words, but in both its broader and narrower definitions in the reading research, decoding’s key focus is linking print to speech.

Decoding is not about semantics, syntax or context, which fall on the Language Comprehension side of the Simple View of Reading equation (Decoding multiplied by Language Comprehension equals Reading Comprehension).

Astonishingly, David Hornsby got his Humpty Dumpty definition of decoding from the Australian Curriculum: (update May 2019: this definition has now, happily, been corrected)

Decode: A process of working out a meaning of words in a text. In decoding, readers draw on contextual, vocabulary, grammatical and phonic knowledge. Readers who decode effectively combine these forms of knowledge fluently and automatically, and self-correct using meaning to recognise when they make an error.

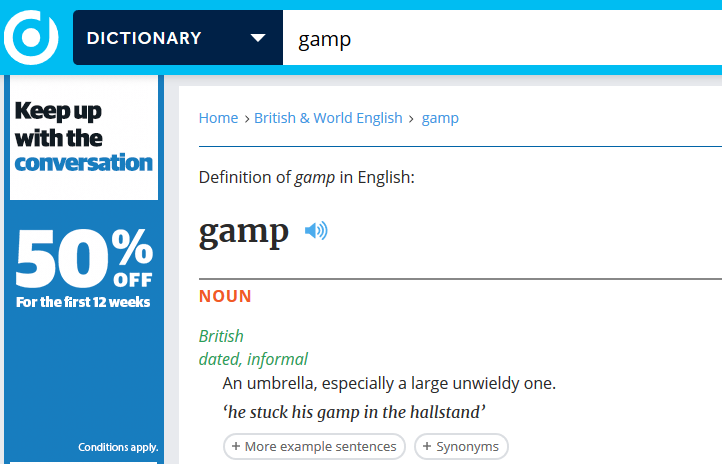

David Hornsby goes on to say you can’t decode the word “gamp” because it lacks meaning, whereas the meaningful word “lamp” can be decoded.

Which made me wonder whether David Hornsby, or anyone from the Australian Curriculum’s Words May Mean Whatever We Choose Them To Mean Committee, has ever been glamping.

I went glamping in 2012 in India, it was marvellous. Our luxury, lakeshore tent even had a plumbed-in toilet, here’s a picture (no, I didn’t ask where the pipes went, or swim in the lake).

If the verb “to glamp” is in my spoken vocabulary, but not in yours, does your reading brain tackle its printed form differently to mine? What if you have an inkling that “glamp” is a portmanteau of “glamour” and “camp”? Can a sliver of meaning slide a word over the decoding line? What if you’ve heard it before, but can’t say what it means?

The word “glamping” was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2016, but people have been glamping for centuries. The Ottoman Sultans were right into it. A 1520 diplomatic summit in France involved 2800 tents and marquees and red wine fountains (hilarious video about The Field of the Cloth of Gold is here, but don’t watch it if you dislike expletives).

In 2012, when I said I was going glamping, was it a meaningful word, capable of (in David Hornsby’s terms) being decoded, or a meaningless pseudoword? Seem like a silly question? That’s because it is.

The boundary between real words and pseudowords is very porous. Words come and go in languages all the time. Think of internet campaigns to revive delightful defunct words like “groak” and “crapulous”. Think of professional jargon and product names. Talk to an eight-year-old enthusiast about Pokemon. Make up a word and google it.

One person’s real word is another person’s pseudoword. Typical kids starting school only know a few thousand words, so almost everything the OED is a pseudoword to them.

An unfamiliar letter string is just an unfamiliar letter string, until you’ve used your writing system knowledge to convert it to one or more plausible strings of speech sounds (decoded it), so you can see if it rings any bells in your vocabulary.

It might only be in your phonological lexicon (i.e. it sounds familiar) or also in your semantic lexicon (i.e. you know what it means). Many words have more than one meaning, so a child might know what “set” means when talking about setting the table or “ready, set, go”, but not a set of tennis. What matters most for learning to read and spell a word is being able to sound it out, and having heard it before.

Decode then comprehend with Professor Afferbeck Lauder

When skilled readers read, they instantly recognise most words, and gain instant access to their meanings. Reading is a lot harder for beginners, who must painstakingly convert the chicken scratchings on the page into sounds, blend them into words, listen to the result and decide whether these are words they know.

Kids with large oral vocabularies, and ones who are good at matching wonky pronunciations of words to correct ones (via set for variability), have the most success.

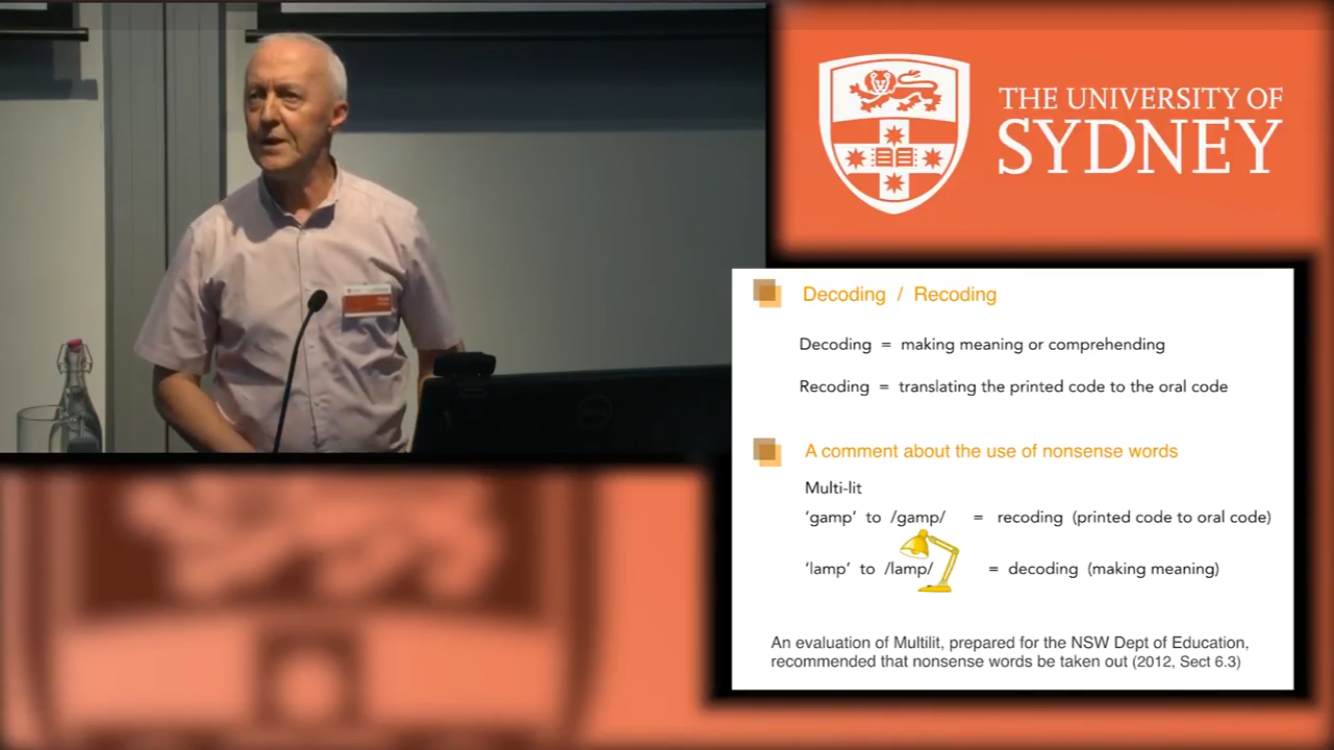

Watching children do this makes me think of my tweenie self the Christmas I received a wonderful book called “Let Stalk Strine” by Professor Afferbeck Lauder (yes, a pseudonym). I lay on the floor reading it aloud, pausing to think, then doubling over with laughter. Its definitions include (my apologies to readers not familiar with the Australian vernacular):

- Air fridge: A mean sum or quantity; also ordinary, not extreme. As in “The air fridge person, the air fridge man in the street”.

- Bare Jet: A phrase from the esoteric sub-language spoken by Strine mothers and daughters. As in Q: ‘Jim makier bare jet, Cheryl?’ A: ‘Narm arm, nar chet”.

- Cheque Render: an ornamental tree with blue flares.

- Dingo: The negative response to the question ‘Jeggoda?’ as in Q: ‘Jeggoda the tennis?’ A: ‘Nar, dingo. Sorten TV.’

- Egg Nishner: A mechanical device for cooling and purifying the air of a room.

I highly recommend the still-available, still-hilarious Complete Works of Afferbeck Lauder to all word nerds interested in A) laughs and B) experiencing having to consciously convert print to speech and then think about what it means, like a beginner. Try it for yourself, here’s p37 of “Strine”:

What else did David Hornsby say?

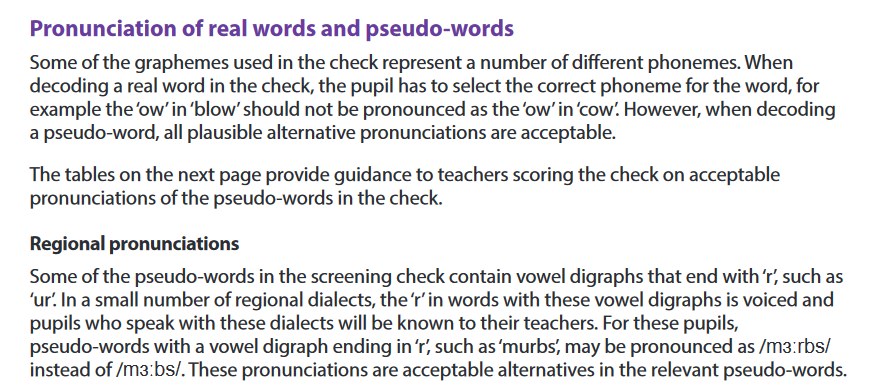

You don’t have to watch David Hornsby’s seminar “The Role of Phonics in Learning to be Literate” for long to find something inaccurate. From 7:30 on the video clock he says the UK Phonics “tests allow only one correct answer, and if you don’t guess the correct one, well, tough … Apart from the fact that this is an appalling test of phonics knowledge, it’s also immoral, because there are three possible correct answers but only one is allowed”.

Here’s a screenshot from page 1 of the administration guidelines for the 2017 UK Phonics Check, I think the most recent version available at the time of Hornsby’s talk:

Hornsby also seems to think synthetic phonics programs involve a radical oversimplification of our writing system, saying (from about 11:00 on the video clock) “We cannot teach phonics as if there’s a one-to-one relationship between letters and sounds” and “our orthographic system, or our spelling system, is absolutely not all about sound, and it’s certainly not about simple letter-sound relationships”, and “English is a morpho-phonemic system in which spellings have evolved to represent sounds (phonemes), meanings (morphemes) and history (etymology).”

All the high-quality synthetic phonics programs I know reflect a good understanding of the complexity of our spelling system, including the way longer words are built from meaningful word parts, and the many fossils from source languages. These programs simplify the system for beginners, but then systematically and explicitly introduce its more complex and less common patterns, in a way that ensures at-risk children aren’t overwhelmed and left behind.

I’m really not sure what else to say about David Hornsby’s talk, except that I laughed out loud at his proposal to call phonics “orthographic phonology”. Why use a simple, well-understood term when you can make up something opaque and polysyllabic?

We’ve known since Jeanne Chall’s 1967 classic text “Learning to Read: The Great Debate” that code-emphasis programs produce better beginning readers than meaning-emphasis programs. More recent scientific research has only strengthened this finding. Yet people like David Hornsby continue to promote meaning-emphasis approaches, which leave far too many at-risk and disadvantaged children behind.

P.S. Before declaring in a public forum that a word you don’t know is meaningless, perhaps it’s wise to check the dictionary.

You’ve written yet another brilliant post, Alison. I’ve added it to the thread featuring responses to David Hornsby’s talk which, understandably, caused much disquiet:

http://www.iferi.org/iferi_forum/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=1051&p=2159#p2159

Thanks! I’m just adding a screenshot of the dictionary definition of “gamp” to the post, it’s an old word for “umbrella”, ha ha, I wish I’d thought to google it before. Wendy Savaris did so this morning and also found it’s also a weaving sampler, and of course there are a number of other definitions. This tosh about there being a clear and present and impervious boundary between real and nonsense words really needs to be put to bed.

The two hours of my life I regret the most involved sitting through an employer-imposed professional development by David Hornsby. When I asked about how his approach to teaching literacy specifically targets children with a specific learning disability, he said some something like

“Well aren’t those the poor little kiddies we all lose sleep over?”, and then unsurprisingly changed the subject.

What an excellent exploration of the silliness that some people will bring to their ideological position that would prefer if phonics didn’t play as important a role in learning to read as it actually does!

Thank you!

The problem starts in Education faculties which no longer see their role as teaching teachers how to teach (probably because they don’t know how to). They see their purpose as two fold 1. inducting teachers into a particular identity ie as innocent victims of vicious forces who want to do stuff like finding out if kids are learning and 2. wittering on about colonialism.

Abolish ed faculties. Now. The rot is too pervasive. Adopt the German model of teacher preparation.

Thank you Alison. Wonderful & informed critique, as always. I’ll be sure to share your post with anyone who mentions the ‘H’ name in ‘phonics education’.

Brilliant response- bluddy marvless

Thanks for making my tired brain work to read that slang! Though I do think there’s hints of a New Zealand accent there! Just been to a great 2 day session with principals and the Education Changemakers to support school exec teams planning to bring in effective change to their schools, including strong phonics programs! Lots of good stuff is happening in DoE schools in NSW around effective reading. I fear for Queensland education who have embraced David Hornsby in a big way.

I’m new to this blog. Allison who? I need to give credit to you good sense when I quote from this.

Cathryn Kelshall

Chair, Dyslexia Association

Trinidad

West Indies

Hi Cathryn, it’s Alison Clarke and my info is here: https://www.spelfabet.com.au/about-spelfabet

Thanks for a great article.