The Language, Learning and Literacy conference – Kathy Rastle

6 RepliesKathy Rastle was another keynote speaker at last week’s great Language, Literacy and Learning conference whose topic is directly relevant to this blog.

You might remember her as a co-author of last year’s influential paper about Ending the Reading Wars, and of this related article (both highly recommended reading).

Hers was the final keynote of the conference, but I met her on the first day. Being a dairy farmer’s daughter who went to Warrnambool High School, I’m still always a little amazed when people with titles like Professor and Head of the Department of Psychology at Royal Holloway, University of London say “hi, I’m Kathy”, and are utterly smiley, nice, and not the least bit pretentious.

Here Kathy is (on the right) with the also-legendary and lovely Lyn Stone (on the left) and Sarah Awesome (AKA Asome) of Bentleigh West PS, (check out their NAPLAN Year 3 spelling gain here!) at the conference Sundowner drinks. However, in the interests of showing proper, gender-neutral academic respect I’ll use her surname from now on.

Prof Rastle has published a paper which says a lot of what she said at the conference, so you might want to skip straight to reading that. Below is my summary of her conference keynote main points, which I hope whets your appetite for more sustained silent reading (ehem) on the topic, or provides a bit of spaced practice to help consolidate the ideas.

Ancient writing had no spaces and was always read aloud

There are no spaces between words in spoken language, and like speech, ancient writing had no spaces. It was designed to represent the sounds of speech, and to be read aloud. This converted the lines of letters on the parchment/stone/clay tablet back into a stream of spoken sounds, which listeners (including the reader) could then understand.

The idea that print represents words and should be read rapidly and silently seems to have arisen after spaces were inserted between words, probably first by Irish monks learning Latin as a foreign language.

Spoken language is a lot more complex than just a string of sounds, but all the intonation, facial expression, gesture etc that adds meaning is stripped away when sounds are written down. Modern writing conventions help flesh out these bare bones.

The modern skilled reader analyses letters and letter positions, word parts and meanings and grammar, plus draws on general and linguistic knowledge (figurative language, causality, inferencing etc), and this places high demands on working memory and executive skills. We have a debate about how to teach reading because the end goal is now immensely complex.

However, novice readers shouldn’t be expected to learn to read by imitating skilled readers, any more than novice cyclists should be expected to learn to cycle by imitating skilled cyclists.

Spelling-sound knowledge provides the hook into oral language

Children usually start learning to read after they have developed most of the speech sounds of their language, and a large vocabulary of spoken words. By becoming aware of the sounds in their speech, and linking these to letters on the page, they build phonic knowledge, which makes it possible for them to sound words out.

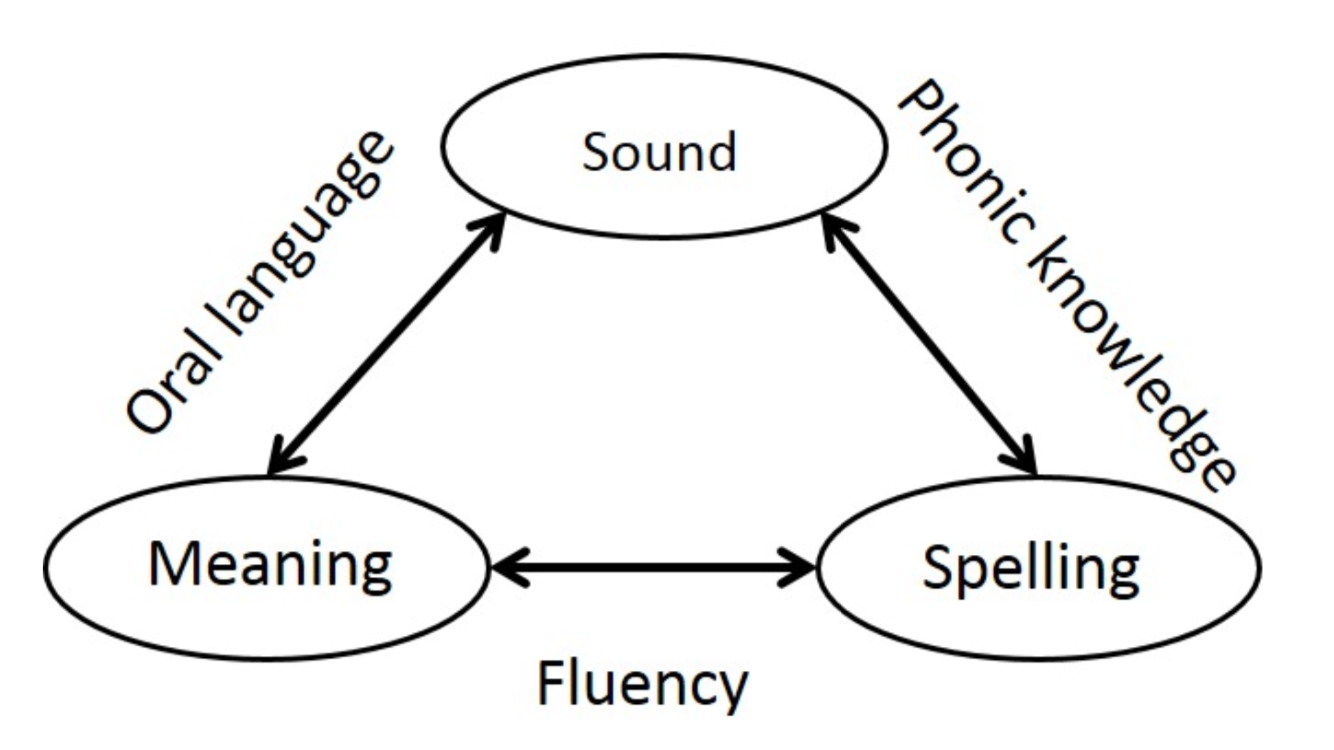

If these words are in their spoken vocabularies, they can with practice then start mentally linking the printed word to its meaning, and thus read more fluently. Here’s Rastle’s diagram of how word-level reading works:

Systematic phonics explicitly teaches children how to link speech sounds to letters and letter patterns, so that they can apply this knowledge to new words. The average five-year-old is exposed to about 5000 words, but skilled adult readers can recognise ~70,000 printed words. There is simply no way any education system could teach them all, so most are self-taught.

Learning spelling-sound mapping

Taylor, Davis and Rastle (2017) taught a group of adults a new vocabulary written in an artificial script. Half were taught to focus on the relationship between print and speech sounds. The other half were taught to focus on the relationship between print and meaning.

The adults taught to focus on print-sound relationships were better at reading the words aloud, but also better at saying the meanings of the words.

The conclusion: “Meaning-based training hurts performance on reading aloud; gives no additional benefit to comprehension”.

Of course a learner’s ability to link both sounds and print to meaning is dependent on the strength of their oral language system (there’s an interesting paper about this here).

The risks of “balanced literacy” and “multicueing”

Rastle says and I quote: “Unlocking spelling-sound relationships is critical in alphabetic reading acquisition, a fact that follows from the writing system”. This is supported by many years of research evidence.

Meaning-focussed “balanced literacy” or “multicueing” type teaching risks wasting limited instructional time, and undermining phonic learning.

Can children discover sound-spelling relationships through print exposure?

Research by Evans and Saint-Aubin (2005) showed that during shared storybook reading, young children were mostly looking at the pictures, not the printed words.

Rastle says it’s “unlikely this could be a major vehicle for development of print skills without other forms of systematic instruction”.

What do skilled readers know about sound-spelling relationships?

Because of irregularities in the writing system, there is considerable variation in the phonic knowledge of skilled readers, research has shown.

Most adults will pronounce the highly regular pseudoword “bamper” the same way, but give many different pronunciations of “eluch”, varying both sounds and word stress.

Phonic knowledge is necessary but not sufficient for skilled reading.

From novice to expert

A novice reader becomes a skilled reader through massive text experience over many years. However there is huge variation in children’s text exposure. Anderson, Wilson and Fielding (1988) found that in a group of Grade 5 children, the weakest readers read only about 60,000 words per year, while strongest readers read 6,000,000 words per year.

To quote Rastle again: “Reading for pleasure really matters, and phonics instruction doesn’t prevent that, it enables it.”

We continue to increase the number of words we can recognise automatically throughout the lifespan, especially during periods of education.

English sacrifices spelling-sound regularity for spelling-meaning regularity

Knowing how words are constructed from meaningful word parts (morphemes) considerably reduces the massive learning-words challenge.

If you know the word “develop” and the relevant affixes, then you can more quickly grasp “develops”, “developing”, “redevelop”, “underdeveloped”, “developmentally” and so on. Over 80% of English words have more than one morpheme.

Particular spellings in English are reserved for particular meanings, and when these conflict, spelling-sound regularity is sacrificed for spelling-meaning regularity. For example, “ed” means past tense, so we write “busted”, “snored” and “kicked” not “bustid”, “snord” and “kickt”. There aren’t many words ending in “ed” that aren’t past tense verbs.

This makes meaningful information in printed English highly visible. When adults in experiments are asked to give the grammatical category of pseudowords, most know (for instance) that the “ous” in “domous” makes it an adjective, and the “ness” in “rabness” means it’s a noun.

Rapidly analysing words at the morphemic level takes a decade or more of reading experience. Explicit teaching might speed this up.

The Reading Wars

Literacy policy in the English-speaking world is a dog’s breakfast of phonics and/or meaning-based teaching approaches, with vast policy gaps beyond the early years. This lack of evidence-based education has consequences for hundreds of thousands of children each year.

Low literacy is widespread and has massive consequences for individuals, society and the economy. It is a major contributor to inequality.

The mandatory Phonics Screening Check in the UK is helping to enhance teacher knowledge, and some broader benefits are starting to emerge, especially to those who enter school at risk of reading failure (see Machin et al 2018 for more details).

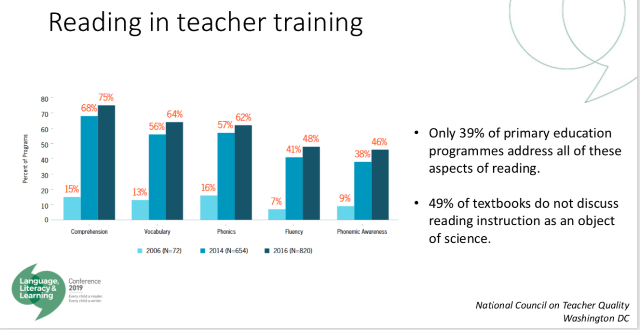

Teacher training programs tend to be woefully inadequate at equipping teachers to teach reading according to the best available evidence. Here’s Rastle’s slide showing how many initial teacher education programs in the US were teaching each of the Big 5 aspects of reading in 2006, 2014 and 2016:

Conclusions

- Reading begins with oral language.

- Children learn spelling-sound relationships through phonics. This is highly effortful.

- They then develop fluency, learn high-level regularities, build vocabulary and release cognitive resources for comprehension.

- Writing represents spoken language but also differs from it in important ways.

- Reading builds on spoken language, but becomes more detached through instruction, practice and appreciation of information in writing.

Those key readings again (both open access, yay, thankyou, Kathy, Anne and Kate)

Writing systems, reading and language by Kathleen Rastle (2019)

Update 15/4/19: Thanks to Caitlin Stephenson for pointing out this great, free webinar by Kathy Rastle on YouTube:

Fantastic! Thanks Alison.

I thought Kathy Rastle’s key note address was fascinating. It linked ‘writing’ in ways I hadn’t thought about before. Can’t wait to read more of her academic articles. Move over Stanislas… I have a new heroine!!!

Another brilliant post, Alison (and I’m not just saying that because you were so nice to me in it!). Love the photo too. I’ll treasure that one!

Great summary of the research and its implications for teaching literacy. Retaining the use of distinctive spelling for imported words is also immensely helpful in signifying a departure from standard English pronunciation. It is also really useful when learning source languages.

“Move over Stanislas” indeed!

I spoke to Stanislas Dehaene about my own research and teaching interest in biscriptal learners of English, particularly Chinese-background learners. He was very Euro-centric, and somewhat misinformed about how Chinese characters and ‘pinyin’ operate. He’s terrific on his home turf, but he’s not particularly interested in the cross-cultural dimensions of reading.

Kathy Rastle, by comparison, was far more international in outlook. She is ‘full bottle’ on different scripts and endorsed the fact that writing systems form the basis of reading systems, and she has done some early research with a Japanese biscriptal learner of English.

Kathy Rastle is my new reading hero, too!

Thank you Alison. Your summaries are very much appreciated.

Thank you Alison. i like this article, and your summaries are very much appreciated.