Summer holiday groups at Spelfabet

0 Replies

Bookings are now open for our intensive explicit, systematic synthetic phonics therapy groups in the week of 15-19 January 2024.

These are for young children (in school Years F-2 in 2023) who need extra help with learning to read and spell words by sounding them out.

Each group will run for an hour a day, and include plenty of games and fun. We will provide daily homework to complete and bring to the next session.

The groups will be:

| Time | Skill level | Example words targeted |

| 8.45am to 9.45am | Beginners: VC and CVC words. | at, in, hop, bus, red, fan, big |

| 10.15am-11.15am | Adding common suffixes to base words, doubling final consonants as needed. Introducing three “long” vowels with consonant-e/split/silent final e spellings, and when to drop final e before adding a suffix. NB if you have a Year 3-4 child who needs this level of work, we may run a second group for them at 11.45am. | bat-batting, swim-swimmer, hop-hopped, run-runny, shade-shady, time, timer, hope, hoping |

| 11.45am to 12.45pm | Adjacent consonants: CVCC, CCVC, CCVCC, CCCVC, CVCCC. | help, list, trap, stop, crust, strip, jumps |

| 2.00pm to 3.00pm | Consonant digraphs. | wish, chat, fetch, this, when, quick, sing |

We will provide all the necessary resources, including specialist take-home readers. We have a maximum of four children per speech pathologist in our groups, to keep the pace/intensity high. We match children carefully and ask that everyone comes prepared to attend all sessions and do all the homework.

Our groups will be held at our North Fitzroy office in Melbourne’s inner north, with attendance by appointment only. Spaces are limited, and upfront payment for all group sessions is required to secure a child’s place. The cost of a week’s program is $720, which covers all sessions, materials and planning time, plus a brief final report with recommendations. Missed sessions are non-refundable. Private health rebates may apply, depending on your level/type of cover, but Medicare only provides rebates for individual therapy sessions.

Children not already known to us need to attend an assessment session with us before joining a group. This allows us to check whether we have a suitable group, and helps us cater for any special needs/interests. If we don’t have a group matching a child’s skills and needs, we can usually suggest other intervention options.

Please contact Tiana Knights on admin@spelfabet.com.au, (03) 8528 0138 or text 0434 902 249 if you’d like to find out more about these groups, or book an assessment for a struggling reader/speller.

What do kids’ names teach them about spelling?

0 RepliesThe first word a child often learns to read and write is their own name. What first impression of our writing system does this give little Charlie, Chloe and Charlotte?

Our current crop of 5-year-olds was born in 2018, so I googled most popular baby names 2018 and looked for names that wouldn’t surprise a child with complete faith in ‘sounds of letters’, alphabet song type phonics.

I found only one name: Max. Even that would surprise kids whose poster/song says letter ‘X’ represents /eks/ as in ‘x-ray’. Add Quinn if you know a doubled consonant is usually pronounced the same as a single one, and your poster/song doesn’t say letter ‘Q’ by itself represents /kw/.

However, most kids’ names have more than one syllable, and contain at least one unstressed vowel. Let’s assume kids aren’t phased by vowel reduction or doubled consonants. Now we can sound out Emma, Ella, Camilla, Madison, Elena, Addison, Bella, Stella, Anna, Allison, Benjamin, Cameron, Adam, Landon, Colton, Ezra, Hudson, Dominic, Jameson, Evan, Declan, and Weston. A total of 24 names out of 200.

Hmm. Let’s add names containing ‘long’ vowel sounds represented by one letter (‘a’ in apron, ‘e’ in even, ‘i’ in icy, ‘o’ in open, ‘u’ in unit). IMHO the best thing about letter names is that the vowel names are also relevant sounds (but kids who extrapolate this to consonant letters tend to write ‘spl’ for ‘spell’, ‘pn’ for ‘pen’ and ‘cr’ for ‘car’). A child able to manipulate vowel sounds in words can now sound out Ava, Zoe, Maya, Penelope, Lila, Nova, Hazel, Violet, Eva, Mason, Logan, Jacob, Leo, Caleb, Owen, David, Samuel, Eli, Nolan, Roman, Rowan, and Jason.

This brings us up to 46 of 200 names, or 50 if we count names with ‘long’ vowel sounds written with ‘split’/VCe/silent final e spellings: James, Zane, Miles, Grace, (though she has a funny /s/ spelling), and Luke (though his vowel sound is really /oo/, not /ue/ as in ‘tune’).

Three-quarters of this sample of kids’ names still contain unexplained spellings. I don’t understand why being able to spell one’s own name is considered such an important milestone for tinies. Spelling names can be very hard, though Vaughan, Traigh, Clodagh, Siobhan, Niamh and Leigh weren’t hot in 2018.

Kids can make more sense of unexpected spellings in their names (and other words) if they know:

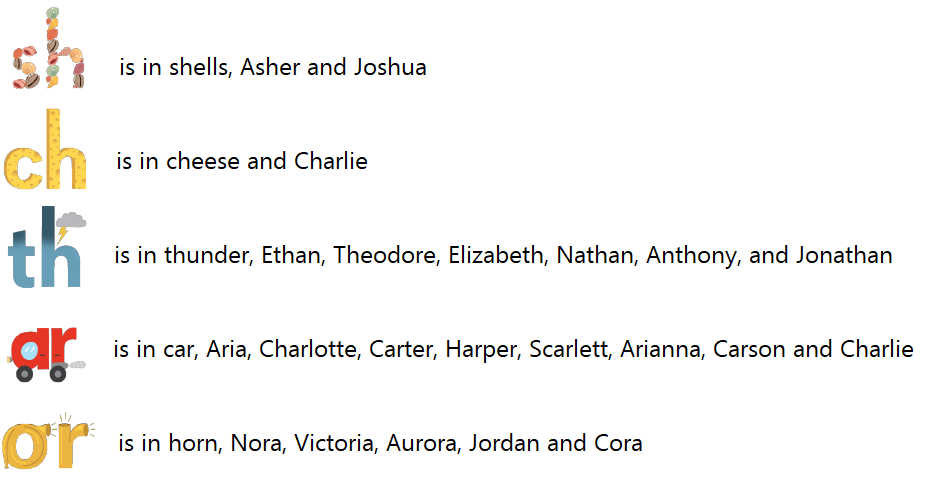

- There are more speech sounds than letters, so we write many with letter combinations.

- Some spellings represent more than one sound.

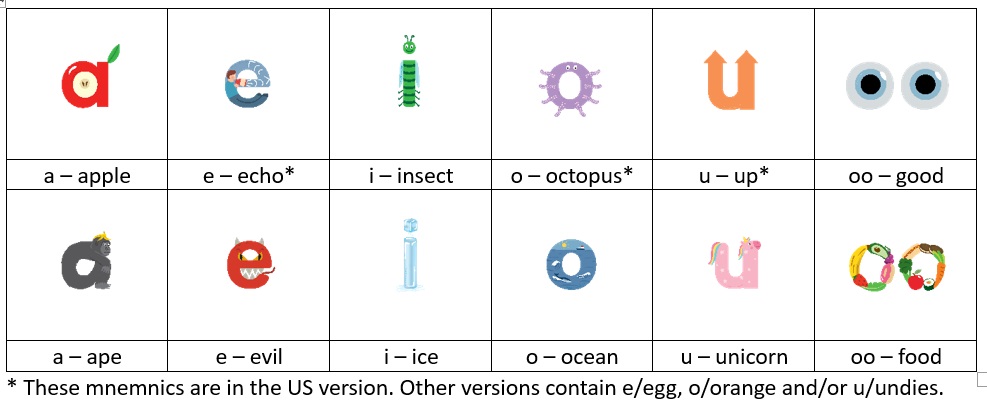

Our Embedded Picture Mnemonic desk mats are one simple tool which can help teach these concepts. They have the alphabet on one side, and the other speech sounds on the flip side, for example:

They also show shared spellings, as at the start of Asher and Ava, Evelyn and Ethan, Isabella and Isaac, Olivia and Owen, the ‘u’ in Hunter and Samuel and the ‘oo’ in Brooklyn and Cooper:

Confusion over harder sound-spelling relationships in names can be assuaged by teaching kids that most sounds are spelt a few ways, for example:

- The sound /ee/ is written ‘i’ in Sophia, Olivia, Aria, Amelia, Mia, Mila (depending on pronunciation), Aaliyah, Eliana, Arianna, Victoria, Emilia, Liliana, Lillian, Gabriella, Maria, Gianna, Naomi, Juliana, Vivian, Julia, Ezekiel, Damian, Xavier, Adrian, Gabriel, Sebastian, and Liam.

- /ee/ is written ‘ey’ at the end of Riley, Aubrey, Kinsley, Hailey, Paisley, and Audrey.

- /i/ is written ‘y’ in Dylan, and is unstressed in Adalyn, Evelyn, Madelyn, Brooklyn, and Jocelyn.

- /ie/ is written ‘y’ in Ryan, Wyatt, Skyler, Bryson, and Kylie.

- /k/ is written ‘ch’ in Chloe, Michael, Nicholas, Christian (from Greek).

- /f/ is written ph in Sophie, Sophia, Joseph and Christopher (also from Greek).

- /z/ is written ‘X’ in Xavier, Xander and Xena, though sadly the Warrior Princess’s name wasn’t trending in 2018 (again, Greek!).

During a recent conversation about where words come from, a tween with an unusually-spelt name told me she’d always wondered about the spelling of her name.

Please don’t leave the kids in your life wondering.

Shallow and deep phonics

18 Replies

My last blog post copped a little flak for its focus on the Victorian Education Department’s top two pieces of advice for parents when their children are stuck reading a word, both of which start with the sentence, “Look at the picture.” (see p14 of this document).

This is very bad advice because it directs children’s attention away from the key information required for good word-level reading. It’s based on the idea of multi-cueing/the three-cueing system, which is scientifically-debunked nonsense. A complex but excellent explanation of why can be found here, and the actual role of context in reading is explained well here.

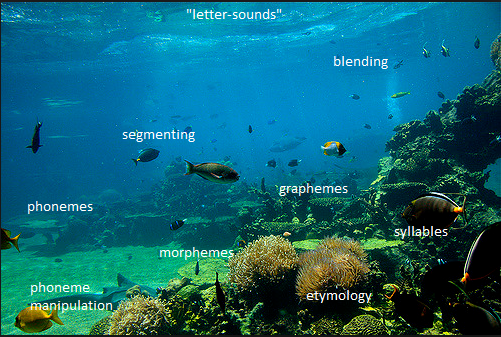

To read an unfamiliar word, children need to take it apart into spellings (graphemes) e.g. “n”, “igh” and “t”, not “ni”, “g” and “ht”, associate these with the relevant speech sounds (phonemes) and blend them into a word. With practice, familiar words are unitised in memory, via a process called orthographic mapping, and no longer need to be sounded out, they become instantly recognised.

Unfamiliar words of more than one syllable must be sounded out a syllable at a time. Earlier syllables must be held in memory while later syllables are worked out, making long words harder.

Once a printed word is converted into a spoken word, its meaning can be accessed, if it’s known. But even if a child doesn’t yet know what a word means (i.e. it’s not yet in their semantic memory), having heard it before (i.e. having it in their phonological memory) kick-starts the process of putting it into long-term memory for instant recognition. Over time the child can learn and refine its meaning(s), and how to use it, by hearing and seeing it in use. (more…)

Decodable texts and lesson-to-text match

11 Replies

A state election looms here in Victoria, and parent-run group Dyslexia Victoria Support (DVS) is petitioning politicians to provide decodable books to all kids starting school in 2019.

Decodable books provide the reading practice for phonics lessons. They include sound-letter relationships and word types learners have been taught, plus usually a few high-frequency words with harder spellings needed to make the book make sense, which are also pre-taught.

Decodable books would replace the widely-used predictable/repetitive texts, which encourage children to guess and memorise words, not sound them out.

At the moment, children might be learning about “i” as in “sit” in phonics lessons, but take home a predictable text that might contain words like “find”, “ski”, “shield”, “bird”, “friend” or “view”. Instead of helping kids practise the sound-letter relationships they’ve been taught, their home readers can undermine this teaching.

DVS’s campaign hit the statewide media this weekend, yay, with an article called “Dull, predictable: the problem with books for prep students” in Fairfax newspapers.