Can teaching be toxic?

5 Replies

A new batch of 5-year-olds are soon starting school, and on current statistics, about one in six of them will end up functionally illiterate.

I didn’t make that figure up, it’s from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. If you want to know more about the Australian literacy data, see this earlier blog post. Similar data apply in other English-speaking countries, although the most recent batch puts Australia at the bottom of the pile.

Children at risk

Children are at risk of not learning to read/spell, and thus not being able to use reading to learn (see this other, earlier blog post) if:

1. Their speech and/or language development has been delayed, or they’re not very aware of sounds in words, for example, they can’t make up or identify words that rhyme, or tell you whether two words start with the same sound, and

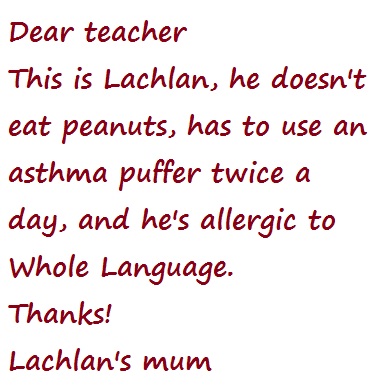

2. They’re taught via teaching methods generally known as either “whole language” or “balanced literacy”, which is basically whole language with some phonics on top.

How do I know what literacy teaching methodology our school uses?

If your young child is being taught to memorise high-frequency words and encouraged to attempt to read ordinary children’s books, rather than books with controlled spellings (decodable readers – more on these soon), then the second risk factor applies to her/him.

How do I know if my child has weak phonemic awareness?

It’s hard to be sure that risk factor 1 doesn’t apply to your child, making him or her effectively allergic to whole language/balanced literacy teaching approaches.

Some schools get a Speech Pathologist to screen all their preps’ speech-language skills and awareness of sounds in words, and then provide extra input to those identified as being at risk, but not many.

What can be done

Now the good news: it is possible to give children pretty good “inoculation” against illiteracy. Only a very small number of kids should still have problems, many fewer than at present.

It’s done using a teaching method called synthetic phonics, which has been conclusively shown to work better than other methods at getting all children started at reading and spelling.

The Scottish research

Literacy-teaching methodologies have regularly been the subject of large-scale, long-term, scientific research. For example, in a place called Clackmannanshire in Scotland, children who learnt via synthetic phonics ended up three years ahead of the national average on reading.

Another, very disadvantaged place in Scotland called West Dunbartonshire used synthetic phonics as a key part of an overall teaching approach which stamped out illiteracy entirely in their schools by the start of secondary school.

In reviews of teaching methodology all round the English-speaking world, synthetic phonics have been recommended. Nobody seems to be allergic to synthetic phonics, so if your school’s not using it yet, and you can’t get them to take it up, you can administer a dose of it yourself at home.

Start from sounds and their spellings, not words

While whole language and balanced literacy methodologies start off focussed on written words, synthetic phonics starts off focussed on spoken words, their sounds and their spellings.

Children are taught just a few sounds and letters at a time, and use these to build little words and write them down. They also read little books containing only these spellings, and play games using these sounds and letters.

Then more sounds and spelling are systematically and rapidly added to the mix, until learners can write and read heaps of words. There are lots of programs and activities that work along these lines listed here.

You know it makes sense

Synthetic phonics is a bit like teaching children to cook by first introducing them to very simple recipes and made with just a few easy implements, and then showing them one or two new things at a time.

We don’t introduce beginner cooks to very sharp knives, hot pans and complicated equipment and recipes, and neither should we introduce absolute beginner readers/spellers to multiple complicated spelling patterns.

But surely the experts know best?

It seems bizarre that in this day and age, schools aren’t teaching early literacy in the best way possible. We can send rockets to Mars, and understand David Lynch movies (well, I personally can’t, but…). However, history is littered with instances of the majority taking the wrong advice from experts, sometimes with disastrous consequences.

Remember Doctor Benjamin Spock, the famous paediatrician who told parents to put babies to sleep on their stomachs? Thousands of parents followed his advice, thus putting their children at greater risk of SIDS.

Thousands of mothers also opted to give their babies infant formula instead of breast milk, believing it was the right thing to do, until scientific evidence conclusively showed that breast is best.

Experts can be very wrong, so what matters is the evidence. Australia’s 2005 National Inquiry into the teaching of literacy reviewed all the evidence, and came down on the side of synthetic phonics. Its recommendations are yet to be implemented.

Inoculate your kid(s) against illiteracy

If you want to proactively inoculate your child against illiteracy, you’ll find lots of good resources, some of which are free, here. There are also good, free activities on the internet and free iPad apps, plus lots of good affordable ones (sorry, I haven’t got an Android device, but if someone wants to lend me one I’ll happily review their apps).

If you want to encourage your school to implement synthetic phonics, I wish you all the very best, and let me know if I can be of any help.

Likewise I hope you’ll be inspired to nag your local library to get some decodable books, and otherwise get the word out in your local community about how to inoculate all the local kids against illiteracy.

The work you refer to in Clackmannanshire, Dunbartonshire supported by the research carried out at Strathclyde University together with a great deal of work carried out by a few dedicated people over many years since Clackmannanshire prove that if synthetic phonics was taught well and rigorously in early years schools, illiteracy would become a thing of the past in all English speaking countries. The status quo is however, very different from this Utopian ideal and there is not a single shred of evidence to suggest that this is likely to change any time soon. It is also important to recognise that the pioneers of SP you mention see SP only as the central strand of a multi-strand approach. They distance themselves formally form the idea of SP as an exclusive tactic to teach reading.

This means that for many years (probably many decades) to come, while the good fight is being fought, tens of thousands of children will continue to graduate to secondary school and ultimately to leave school, unable to read and write confidently.

It is beyond doubt that rhe foundation of good literacy skills is mastery of the letter-sound correspondences. If the illiteracy problem is to be overcome, teachers will have to keep their minds open to the fact that while letter-sound correspondences have to be mastered, HOW they are mastered is unimportant. A situation is arising in which many teachers believe that there is SP, there is only SP and there is nothing other than SP which will secure their mastery, This is self-evidently untrue and the fact is that many generations of children somehow became wholly literate without the benefit of a single SP lesson.

What is to become of the thousands of children who continue to graduate to secondary schools with significant deficits in reading skills because of inappropriate early years teaching? One very successful answer to this is that these correspondences can be mastered perceptually without a single phonics lesson. Consider the children in the video who all graduated to secondary school with a reading age deficit of more than two years.

The link is http://youtu.be/d-wlbCFVzto

The perceptual learning approach they used did not involve a single ritual teaching session. As in all perceptual learning situations, the childrnen are given nothing to remember and therefore, nothing to forget. Perceptual Learning is how we all acquired our first language and it is how all successful commercial language organisation such as Rosetta Stone teach languages.

The battle to secure a situation is which SP is universally well taught must continue but we are damaging many children if we insist that it is the only route to literacy because it self-evidently is not.

Eddie Carron

eddiecarron@btconnect.com

Dear Eddie, thanks so much for this comment, I think because I’m a Speech Pathologist and spend my life running up against learners who aren’t just a couple of years behind, but have skills at a 6 or 7-year-old level, when they’re 11 or 15 or 25, I get very focussed on the absolute basics. But of course for learners who do have their literacy foundations in, literacy is much more than being able to blend, segment and recognise and use letter patterns. Your context may be different, but in our local schools the dominant early literacy teaching methodology is still memorising high frequency words plus a sprinkling of initial analytic phonics, so the kids with weak phonemic awareness and language-disordered kids get very lost and confused. A good dose of SP really turns this around and then everyone says, “wow, let’s try that with everyone”, but you’re very correct to be wary of something useful becoming the latest fad that’s overextended to all learners, and then a whole lot of other useful stuff, like fluency, vocabulary and comprehension, is at risk of being thrown out the window. I’m actually not 100% clear from your very nice video exactly what the content of your program is, or whether it’s more about lots of interesting, well-organised practice and encouragement, but I daresay the amazing internets will be able to tell me the answer to that. I will go back through my website and revise any bits that might give people the impression that, because I think SP is the way to go to get basic decoding and encoding happening for beginners, it’s the only thing. Thanks for the reminder about the big picture.

Hi Alison

Thanks for your insightful response.

Like you, I believe that reading competence is a consequence of having mastered the sound/symbol correspondences and that the best way to achieve this is good early years teaching. In England, those who championed this point of view squandered their chance of making a serious difference by becoming engaged by an internecine struggle for pre-eminence by ‘out-SPing’ each other and this has turned them into an irrelevance. A similar thing happened to the RGB3 group in the USA.

The pioneers of SP in Clackmannanshire, Dunbartonshire and Strathclyde distance themselves entirely from the dogmatic corner into which this group has painted itself, supporting instead, an initial teaching philosophy which has SP at its core but which nevertheless leaves room for alternative strands for the small number of children who do not respond immediately to ritual SP teaching.

You are correct to deduce that a perceptual learning approach is about “lots of interesting, well-organised practice and encouragement” because within this experience, the sound-symbol correspondences are intuitively but just as effectively, mastered. It was Albert Einstein himself who said that "Experience is learning. Everything else is just information." That’s all there is to it and as you can see from this school’s video, there are some children for whom this is sufficient to ensure that they will not leave school unable to read and write confidently. About 15% of those who attend his course, graduate in one half term and a similar number in just one term. The strength of this teacher’s strategy is its flexibility – nothing is cast in time-tabled stone.

In some recent work with Year 2 (age 6) non or near-non readers in a group of schools, a perceptual learning approach used over one term only was sufficient to enable them to re-engage productively with the same Jolly Phonics exercises as their more fortunate peers.

I have sent you a copy of the resources which the school in the video has used for the past five years. You will see that they are completely unsuitable as a means of teaching children generally how to read – they are unsuitable because that is not their design purpose.

My best wishes

Eddie

Sorry to hear you say things aren't as rosy on the SP front in the UK as they appear from here, and thanks very much for sending me your materials, I look forward to receiving them. If there is any published scientific research about the efficacy of the approach you use, I'd also be interested to know about it.

I would guess that SP is really well taught in fewer than half of UK schools but the situation is improving and most importantly, much greater emphasis is being placed on SP in teacher training. The danger lies is SP being promoted to the status of religion rather than being regarded simply as the commonsense approach to the teaching of reading in any alphabet-based orthography.

As to perceptual learning, some research has been carried out in many universities but currently the most prominent work is being carried out by Dr Phil Kellman at UCLA. His work covers all aspects of the curricullum but greater emphasis is placed on maths and science teaching. The fact that PL is used exclusively by commercial langauge teaching organisations and that it is how everyone in the universe acquires their first language is important.

In the UK, so far as I am aware, mine is the only practical work being carried out. It is in use in about 100 UK primary schools and in project groups in Northern Ireland and Scotland where schools are not directly controlled by an English government minister. These projects will report at the end of July. There is a core group of secondary schools which use it in Scotland like the one in the video. interestingly there is also a school in New Zealand which places considerable emphasis on perceptual as opposed to ritual learning for children who fail to respond to phonics approaches whether because of some intrinsic learning difference or because of poor teaching. It is called Pukekohe Intermediate School.

Perhaps when the resources CD arrives, you will be able to try it out experimentallty on some very poor non or near-non readers . You can give copies of the CD to parents to carry on the work at home because it only works if it is done daily. You will find that children respond really well to it .

Regards

Eddie