Decodable texts and lesson-to-text match

11 Replies

A state election looms here in Victoria, and parent-run group Dyslexia Victoria Support (DVS) is petitioning politicians to provide decodable books to all kids starting school in 2019.

Decodable books provide the reading practice for phonics lessons. They include sound-letter relationships and word types learners have been taught, plus usually a few high-frequency words with harder spellings needed to make the book make sense, which are also pre-taught.

Decodable books would replace the widely-used predictable/repetitive texts, which encourage children to guess and memorise words, not sound them out.

At the moment, children might be learning about “i” as in “sit” in phonics lessons, but take home a predictable text that might contain words like “find”, “ski”, “shield”, “bird”, “friend” or “view”. Instead of helping kids practise the sound-letter relationships they’ve been taught, their home readers can undermine this teaching.

DVS’s campaign hit the statewide media this weekend, yay, with an article called “Dull, predictable: the problem with books for prep students” in Fairfax newspapers.

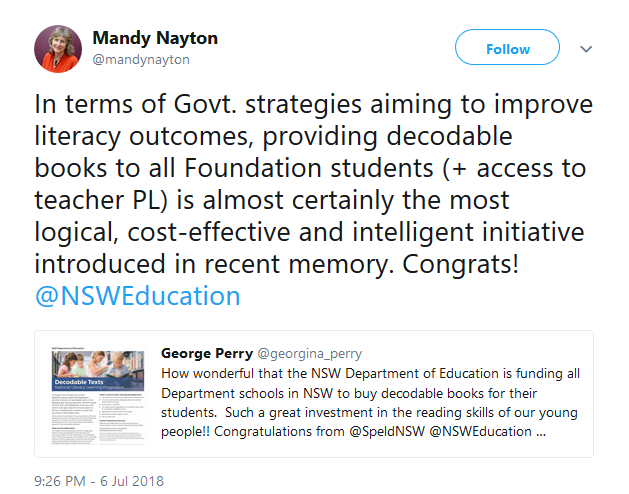

NSW already funds decodable books

The NSW state government has recently given public schools $50 for each child in their first year of school to buy decodable books.

I completely agree with these reactions from AUSPELD President Mandy Nayton and NSW SPELD‘s George Perry:

Several Victorian teachers have recently told me scarce funds are the main barrier to their schools buying decodable books for all their beginners.

Following NSW’s lead in Victoria would not be expensive. 56,766 children are now in their first year at Victorian government schools, so $50 for each child equals $2,838,300. An extra $1,219,050 would extend the offer to the 24,381 preps in non-government schools. Chickenfeed in the context of the state budget.

Does decodable text work?

Professor Tim Shanahan of the University of Illinois Center for Literacy, an internationally recognised authority on literacy-teaching, recently wrote a blog post called “Should we teach with decodable text?”. His point is summarised most succinctly in one of his comments: “No matter what you’ve been told or which group of kids you are concerned about, there is no research evidence supporting the idea that decidable (sic) text works.”

Myself and many others found this odd, as decodable texts aren’t meant to be used in isolation, they’re part of explicit, systematic phonics teaching, and Shanahan was on the US National Reading Panel which said phonics teaching is effective.

More recently, a 2012 systematic review found that “decodability is a critical characteristic of early reading text as it increases the likelihood that students will use a decoding strategy and results in immediate benefits, particularly with regard to accuracy”.

Shanahan admits the lack of a clear, agreed definition of decodable text means the available research is kind of a mess: “with little evident agreement about what decodable text is, what it should be compared with, and what outcomes we should expect to derive from it.” He says, “Perhaps the best study of the problem was conducted by Jenkins and colleagues (2004).”

I was keen to read this article, though since I’m not affiliated with a university, accessing it cost me $AUD59.30 (no, I’m not joking, I agree with George Monbiot that scientific publishing is a rip-off). No wonder there’s a knowledge gap between researchers and practitioners. Anyway, I coughed up, downloaded and read it.

Whatever the text type, learners were prompted to decode

At-risk first-graders in this study were divided into three groups, a control group and two experimental groups who had one-to-one tutoring using the phonics-based program Sound Partners for 25 weeks, 4 days a week for 30 min per day. One group’s reading practice was with decodable storybooks, and the other group read books with uncontrolled spelling patterns. Both groups outperformed the control group, but not each other.

The article says that during reading practice, “If students hesitated for more than 5 sec, or misread a word, the tutor prompted them to use previously taught phonic skills (e.g., isolated specific letters in the word and coached the student to figure out the word), or supplied a letter sound or word, as needed.”

Nobody told these kids to look at the picture and guess, think what word might go there, or otherwise use multi-cueing type strategies. Even when they were reading non-decodable books, these children were encouraged and assisted to decode by tutors who understood phonics. Perhaps this matters as much or more than book type.

I wonder whether book type affects how consistently parents encourage and assist young children to decode, rather than guessing words.

Establishing a useful definition of decodable text

To some researchers, decodable text is text containing only the most regular spelling patterns in the language, i.e. it’s a property of the text alone. From a practitioner’s perspective, this is not an interesting or useful definition, it’s far too simplistic.

Others see decodability as a property of the relationship between text and learner knowledge, so that as children learn more of our spelling code, more books become decodable to them.

However, learner knowledge is usually part of the dependent variable – the thing being tested and measured – in scientific reading research. It thus can’t also be part of the independent variable, which the experiment changes or controls while measuring the effect on the dependent variable.

To help practitioners and avoid research quagmires, the definition of decodability really needs to focus on lesson-to-text match. Practitioners are in control of what they do, not how children respond.

I’d like researchers to define decodable texts as reading practice activities including the phoneme-grapheme correspondences, word types and high-frequency words which have been systematically and explicitly taught, and specify what percentage of words (say, 5%) fall outside this.

Kids should be reading texts they can’t read yet?!

Tim Shanahan’s blog post includes the statement that “even beginning readers should be reading more than decodable texts”. Which seems a bit like saying “even beginning readers should be reading words they haven’t been taught how to read yet”, but perhaps this is yet another problem with definitions.

His definition of reading might be like the Australian Curriculum’s: “To process words, symbols or actions to derive and/or construct meaning. Reading includes interpreting, critically analysing and reflecting upon the meaning of a wide range of written and visual, print and non-print texts”. In which case he might mean that children should be read stories and taken to art galleries and interpretive dance performances. All good, though this definition of reading wouldn’t pass a pub test.

However, I imagine his definition of reading is more like the International Literacy Association’s definition, since he is a past President (along with “father of Whole Language” Ken Goodman and Marie Clay of Reading Recovery fame): “The process of simultaneously extracting and constructing meaning through interaction and involvement with written language”. This could mean listening to others read, I suppose.

He might also mean that beginners should be encouraged to attempt words containing spellings they have never been taught. If he means mainstream kids and about one word in 20 during independent reading, or one word in ten during supported reading, that’s probably fine.

The proportion of untaught spellings which makes a text too difficult is probably highly learner-dependent. Kids with extensive experience of reading failure can, in my experience, quickly melt down and refuse to continue once they start making mistakes.

Self-teaching and signal-to-noise

Shanahan’s over-arching concern seems to be that beginners not be overly shielded from the full complexity of our writing system. Much of what skilled readers know is self-taught. Once we can read at a basic level, we gather data about how words are written through the process of reading (see the Self-Teaching Hypothesis, and this dense but interesting journal article on Reading as Statistical Learning).

Shanahan writes, “Presenting students with lots of decodable text, text that’s much more regular that normal text, might mess up some of these cognitive calculations”.

Well, yes, once kids have the basic knowledge and skills that allow this self-teaching to commence. Until then, it’s all noise and no signal. I’m reminded of the day one of my clients surprised his dad by asking, as they sat on the train at Alphington Station, “Why is there a ‘ph’ in Alphington?”. They’d been through that station many times before, but he only asked about the “ph” after he could sound out the rest of the word.

I’m always delighted when my clients start independently reading environmental print (shop signs, chip packets, car stickers, menus, whatever) aloud. This seems to be an important reading milestone, and one I wish researchers would investigate more closely (or maybe they have and the results are behind an expensive paywall, where I can’t see them).

Shielding beginners and strugglers from knowledge of the full horror of English spelling simply isn’t possible. Today’s kids are surrounded by spelling complexity for most of their waking hours. We can hardly ask them to avert their gaze from every word containing (a) spelling(s) they haven’t yet been taught.

Teaching needs to help beginners and strugglers discern the signals among all the noise. Decodable books strip the noise back, making important signals at first a lot clearer and easier to learn, and they encourage kids to sound words out rather than guessing them.

Another great read, Alison, but such a shame your piece doesn’t belong in the ‘fiction’ section. The conflict continues but change is happening……slowly! Thank you for your wonderful advocacy for all those who struggle to read and for those who are yet to begin their reading journey.

Thanks, Sharon. I’m so happy you think change is happening, I think so too, but the tipping point where everyone changes seems to still be a long way off! All the best, Alison

Another tour de force, Alison! Love the signal and the noise analogy. I take it you’ve read the book of the same title?

Hi Lyn, sorry to take ages to reply, moving offices and going to Adelaide relegated answering blog comments to the backburner for a bit. I have not read a book called “Signal to noise”. Should I? I have a pile of books about a metre high I want to read but never find enough time. I guess that’s true of everyone with a pulse who enjoys reading though, first world problems!

What resources and training is available for adult learners, and instructors, tutors, and teachers???

Hi Reta, sorry to take ages to reply. There are some good adult learning resources, I was talking to a teacher about this the other day. Try the Forward With Phonics resources, http://www.forwardwithphonics.com, and That Reading Thing, https://thatreadingthing.com, plus Toe By Toe is worth considering if you will be relying a lot on volunteers, http://www.toe-by-toe.co.uk. Susan Godsland in the UK has a lot of interesting links here: http://www.dyslexics.org.uk/teenage_dyslexics.htm. Hope you find useful things! Sadly at the moment I am not aware of good phonics training in the adult literacy sector here in Australia, but the Sounds~Write course is relevant to learners needing to do phonics at any age, http://www.sounds-write.co.uk/page-98-australia.aspx, and so are some other programs designed for younger learners.

I totally support the use of cumulative, decodable text for beginners and strugglers. The main issue is when we ask children to read aloud a book ‘independently’. This means that the learner gets the message he or she is expected to be able to read the book (lift the words off the page) by himself or herself.

This is positively cruel if the words are not within the code knowledge the learner has been taught, and has learnt. We see this on the BBC documentary ‘B is for Book’ when a couple of slower learners are presented with situations when they are clearly asked to read aloud words and books that they have no chance of reading – unless, of course, they apply their guesswork either by default (because they have to as they cannot decode the words) or because the prevailing teaching is multi-cueing word-guessing – that is, they have been taught to word-guess as if this is the normal way to proceed to be a reader.

This thread describes this scenario: https://iferi.org/iferi_forum/viewtopic.php?f=2&t=613&hilit=BBC+documenary

What is particularly worrying in the school featuring in the BBC documentary is that the school has clearly adopted a very good systematic synthetic phonics programme so explicit phonics teaching is definitely happening in that school. But the ‘understanding’ of the staff in that school looks as if it is still underpinned by Reading Recovery’s ethos (perhaps training) whereby it is apparently normal practice to face children with reading books that are beyond their ability to read and then ask them to read the book largely independently.

You can see that this is totally off-putting for young learners and for them, it feels like they are the stupid ones – not the teacher. This is surely immoral – but it is happening everywhere.

The issue, then, is ‘independent’ reading and the ‘understanding’ of the supporting adult. I suggest strongly that no children should be asked to read aloud books that are beyond their decoding ability unless it is a ‘shared’ enterprise and the adult is clear that it is the alphabetic code that the child has not yet been taught that causes some difficulty – and that this is made clear TO THE LEARNER.

This is also why I heavily, heavily emphasise the helpfulness of using overview Alphabetic Code Charts from the outset of teaching a systematic synthetic phonics programme. In my work, this could start for the four+ year olds. Tell the children a little bit of background information about the English alphabetic code being the most difficult alphabetic code in the world (because of its history) and that they, the teacher, will need to teach them for a long time, and support them with reading and writing for a long time.

In other words, the difficulties of the English code for reading and spelling are immediately made clear to the children in the sense that this is about ‘the code’ – and difficulties in reading and spelling are not attributed to them as individuals as if they are more stupid than other children. This is a HUGE issue in my opinion.

However, no matter how much I bang on about the helpfulness of sharing this knowledge with children, I don’t seem to get much interest from researchers and bloggers in terms of supporting this suggestion. It could be that they themselves are doing this (using such charts and telling the children how hard the English code is) but don’t think to say as such – or it could be that they have not tried this yet to see if it does indeed help.

For what it’s worth, here is a wide range of free downloadable Alphabetic Code Charts: http://alphabeticcodecharts.com/free_charts.html

Best wishes,

Debbie

As always, I shall be linking to Alison’s excellent blog piece. Her work is a gift to spreading great information about reading and spelling instruction.

Dear Debbie, so sorry for the slow response (I’ve been moving office and snowed under) and THANKYOU SO MUCH for helping me re-find the B is for Book documentary, I saw it a long time ago and decided to write a blog post about Stephan’s understandable and priceless eye-rolling at being asked to read “The little doll is on the table, the little bus is on the table” etc, but then I forgot where I saw it and what it was called. I have just written a blog post about it now, and I hope this encourages people to watch the horrid predictable text lesson he endures and think about it, and decide to (as our Reading League friends would say) do better. Thanks again, I’ve also thanked you at the end of my post. Alison

Teachers employed by the Education Department of Western Australia can obtain research articles at no cost through the Departmental Library. They can request a particular article, or request articles on a particular topic. I’d suggest that teachers employed in government schools in other states find out if this service is available in their state. I know that we are in danger of losing the library service in WA as it is under-utiliised – but this is probably an effect of being under-advertised!

To piggy back off of what Jancy wrote, I have access to my old university’s library as a an alum. Just in case you haven’t checked for that possibility!

More importantly, excellent article and I’m saving it for some teaching I’ll be doing soon on decodable texts.

Thanks so much! Alison