Why doesn’t NAPLAN start in Year 1?

0 Replies

It’s too late to find out a child is struggling to read and write in Year 3. The horse has bolted. It’s no longer possible to provide effective, cost-effective early intervention. Intervention is harder, less effective and more expensive. The damage done to a child’s confidence and motivation can be even harder to undo.

Why don’t we collect national data on reading and spelling skills earlier, in order to better understand learning in the vital early years? There’s been a lot in the media lately about the latest NAPLAN results, which show that a third of Australian kids are still struggling to read and write well. Indigenous, rural and low socioeconomic kids are struggling more than most. This is a serious social justice issue.

Reading and spelling problems start long before NAPLAN shines a light on them. Don’t the NAPLAN people know exactly what all children are expected to know and be able to do in Year 1, in order to measure it?

Well, maybe not. Our National Curriculum contains learning area and content descriptions, but not specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, timed (SMART) goals for phonemic awareness, word-level reading and spelling. The content descriptions for phonic and word knowledge for the first year of schooling are in the red text in the table below. I’m glad I don’t have to work out how to assess them! I’ve added the italics, and in the second column have put some of the kinds of goals for this skill area I’d want if I were teaching Foundation (which I’m not, so I’m sure they can be improved upon).

| National curriculum Foundation phonic and word knowledge content descriptions | Possible SMART Foundation phonic and word knowledge goals |

| Recognise and generate rhyming words, alliteration patterns, syllables and sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. (AC9EFLY09) Rhyme and alliteration are important in poetry, but in early literacy teaching, phonemes are what matter. Segment sentences into individual words; orally blend and segment single-syllable spoken words; isolate, blend and manipulate phonemes in single-syllable words (phonemic awareness). (AC9EFLY10) English one-syllable words can be up to seven phonemes long (e.g. ‘sprints’, ‘strengths’, ‘glimpsed’). Blending and segmenting even two or three sound words is very hard for many young children, and manipulation is even harder. How many sounds/what word structures (VC, CVC etc) are meant here? Recognise and name all upper and lower case letters (graphs) and know the most common sound that each letter represents. (AC9EFLY11) Vowel letter names are relevant sounds represented by these letters, so are useful when sounding out words. But when kids apply the same logic to consonant letters, they tend to write ‘car’ as ‘cr’, ‘left’ as ‘lft’, and ‘enemy’ as ‘nme’. Some research suggests letter name knowledge can interfere with children’s ability to apply the alphabetic principle. Kids must recognise letters, but is letter name knowledge essential in Foundation, especially for at-risk kids who are easily confused by too much information? ‘The most common sound each letter represents’ isn’t always what you might think. Fry’s 1966 large phoneme-grapheme count found 1801 instances of the letter Y as in ‘very’ (/ee/ sound), 211 of Y as in ‘my’ (/ie/ sound), 100 of Y as in ‘system’ (/i/ sound) and only 53 instances of Y as in ‘yard’. The letter O represented /oe/ as in ‘open’ 1876 times, /u/ as in ‘other’ 1723 times, and /o/ as in ‘not’ 1558 times in this count. Our National Curriculum needs to be more precise about sound-spelling relationships. Write consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words by representing sounds with the appropriate letters, and blend sounds associated with letters when reading CVC words. AC9EFLY12 If taught well, most Foundation kids can also learn to read and spell at least VC, CVCC and CCVC words like ‘in’, ‘at’, ‘help’ and ‘from’. Many can even spell /sh/, /ch/, /th/ and /ng/, though the National Curriculum doesn’t count these as consonants, which it defines as: “All letters of the alphabet that are not vowels. The 21 consonants are b, c, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, m, n, p, q, r, s, t, v, w, x, y, z”. Yet ‘vowel’ and ‘consonant’ are terms from linguistics for speech sounds, of which there are 44 in General Australian English. Use knowledge of letters and sounds to spell words. (AC9EFLY13) I guess it doesn’t hurt to state this while there are still kids out there being asked to memorise high-frequency word lists. But which letters, sounds and types of words? Read and write some high-frequency words, and other familiar words (AC9EFLY14) Which high-frequency words? How many? Three? Fifty? How many other familiar words? Understand that words are units of meaning and can be made of more than one meaningful part (AC9EFLY15) Which prefixes and suffixes should be taught in Foundation? Will teachers using lists like the Oxford Wordlist start teaching how words are built? The Oxford Wordlist includes ‘lot’ and ‘lots’, ‘cousin’ and ‘cousins’, ‘live’ and ‘lived’, ‘play’, ‘played’, ‘playing’ and ‘playground’, and ‘friend’, ‘friends’ and ‘friend’s’, as though they’re unrelated words. | Blend, segment, read and spell at least 90% of vowel-consonant (VC), CVC, CVCC and CCVC words containing the following sound-spelling relationships: Vowel sounds as in ‘at’, ‘red’, ‘him’, ‘on’, ‘up’, ‘put’. Consonant sounds as in ‘bib‘, ‘cat’, ‘did‘, ‘frog’, ‘got’, ‘him’, ‘jump’, ‘kit’, ‘leg’, ‘mum‘, ‘nest’, ‘pop‘, ‘run’, ‘sift’, ‘is‘, ‘ten’, ‘vet’, ‘win’, ‘yet’, ‘zip’, ‘shop’, ‘chin’, ‘thin’, ‘them’, ‘swing‘. Blend, segment, read and spell at least 60% of words with: CCVCC, CCCVC and CVCCC structures and the above sound-spelling relationships. Position-related consonant spellings as in ‘quit’, ‘box‘, ‘off’, ‘well‘, ‘mess‘, ‘buzz‘, ‘luck‘, catch, dodge, ‘when’, ‘bank’, ‘solve‘. Inflectional suffixes: regular plural (s, es), past tense (ed), third person (s, es), present progressive (ing), possessive (‘s, ‘), comparative (er), superlative (est), past participle (en). Derivational suffixes: agent noun (er), adjective (y), adverb (ly). Final syllable -le as in bottle. Contractions as in ‘isn’t‘, ‘can’t‘, ‘don’t, ‘it‘s‘. Read at least 60% of these not-yet-fully-decodable words in connected text: the, we, she, he, me, be, a, of, are, you, your, for, or, more, before, her, sister, over, under, after, were, to, do, who, two, room, zoo, too, soon, what, was, want, where, there, here, came, name, made, make, ate, I, like, time, side, so, go, no, home, hope, one, once, love, some, come, say, day, play, they, boy, toy, now, down, new, few, out, our, house, about, found, first, girl, car, park, look, good, book, could, should, would, saw, all, call, ball, my, by, try, very, only, family, happy, see, been, three, sleep, eat, real, said, because, school, friend. |

If you’re in Melbourne and your Year 1 or 2 child can’t do the things in the right-hand column above, you might like to bring them to one our school holiday groups.

It’s up to each state to interpret the National Curriculum, so they can add more clarity and specificity, I guess. Two states – NSW and SA – now test all Year 1 students’ phonics skills, and there is a free, online Australian Year 1 Phonics Check available for anyone to use, along with a phonics progression.

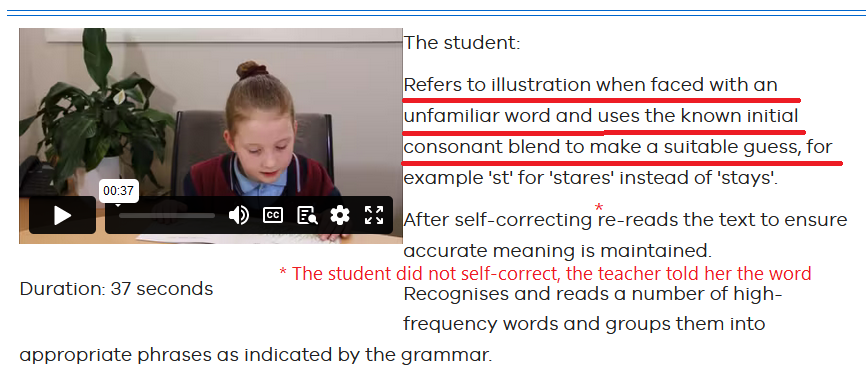

My own state, Victoria, has devised its own, watered-down version of the Year 1 Phonics Check (10 questions not 40). I agree with critics’ description of this: hopeless, and encourage Victorians to tell the current Parliamentary Inquiry into the state education system this, and whatever else you think needs saying, before 13th October. We’re supposed to be the Education State, but our Education department is still recommending the use of Running Records, and the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority website still promotes guessing words from pictures and first letters. The picture and black text annotation below is a screenshot from the VCAA website (the cranky red additions are mine).

Year 1 children’s word-level reading and spelling skills will probably only be assessed consistently across the country if this becomes part of NAPLAN. In the meantime, the growing number of teachers around the country who understand learning science (often thanks to grassroots groups like RSS, TFE or SBP) will keep setting high, SMART reading and spelling goals for young learners, teaching directly, explicitly and systematically, and checking their progress with more valid and reliable assessments than Running Records. I just wish they had more system-wide clarity and help.

Photo at top: https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-oyqyx

New word-building videos

0 RepliesI’ve made three very short videos (each under 90 seconds) showing how lots of long words are built by adding prefixes and suffixes to base words. The tiles depicted are from the Spelfabet Moveable Alphabet and Affixes, many of which flip over, making it easy to demonstrate juncture changes e.g. how ‘y’ changes to ‘i’ in ‘funny-funnier’, and final consonants double in ‘run-running’ and ‘hop-hopping’.

The aim is to minimise wordy explanation, and maximise demonstration, so I’ll stop explaining them now, and let them speak for themselves. Hope you like them.

Society for the Scientific Study of Reading conference: day 3

0 RepliesI’ve finally found time to summarise the sessions I attended on the last day of the SSSR conference. Here’s what I learnt (sorry if I’ve misunderstood anything).

Parent advocacy about literacy in preschools

Dr Stacey Campbell from Queensland University of Technology said preschool teachers report increasing pressure from parents to teach literacy skills. She collected data about parents’ literacy beliefs and expectations from six early childhood services, using a survey and follow-up interviews.

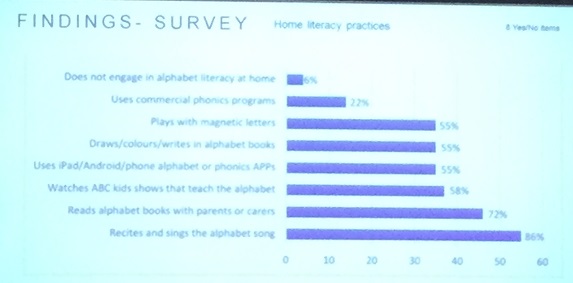

Most parents agreed that both phonics and what Dr Campbell called play-literacy learning (I’m not sure exactly what that includes) were important. Parents of kids in school-based settings were more likely to endorse formal phonics instruction. Most parents wanted play-literacy, rhymes and name writing (poor little Phoebe, Niamh, Jose and Xavier). At home, they used a range of home literacy practices, as per the above graph (sorry it’s a little blurry). I was a bit sad to see that the most common home literacy practice was “recites and sings the alphabet song”, having known so many learners who get letter names and sounds mixed up.

Dr Campbell was asked what preschools in Australia are required to teach regarding literacy. She said we have an early years learning framework, but it’s very generalised/broad/open to interpretation, and what’s taught can depend on whether the educator has a degree or a diploma.

Implementing the Ontario Right To Read report

In February 2022, the Ontario Human Rights Commission released the Right To Read report, finding that reading instruction in Ontario was not meeting student needs. It made 157 recommendations e.g. stop using leveled readers, cueing, and running records, and introduce phonemic awareness and phonics work with decodable text, plus screeners, small group (Tier 2), and individualised (Tier 3) intervention.

A/Prof Deanna Friesen from the University of Western Ontario surveyed 30 teachers about their level of confidence in implementing the report’s recommendations. Beliefs were raised as one major barrier, but respondents felt teachers would try things they thought would make a difference. Other major barriers were lack of training and resources, and class sizes. Providing relevant training and resources were considered the most likely facilitators of change.

Some of the teachers surveyed had done evidence-aligned training since the release of the report, more than half with external providers. Some had funds to buy evidence-aligned resources, but some did not. Some had good resources, but didn’t know how to use them, or feel they had time to learn.

Teachers commented that initial teacher preparation needs to improve, as they paid for their degrees, but didn’t get value. They wanted training including coaching, support and concrete examples at school level. They wanted the school system to provide a list of quality training and resources, and relevant funding, rather than teachers having to find, and sometimes fund, training and resources themselves.

Dr Friesen said the Right To Read report had been an influential catalyst, but implementation will depend on listening to educators about their needs for success. The new 2023 Ontario Language Curriculum is better aligned with scientific research than previous versions, but Ontario school boards have a lot of control, which leads to variability in teaching, and sometimes non-co-operation with top-down directives.

Reciprocal learning relationships in reading and maths

Prof Arne Lervåg of the University of Oslo spoke about statistical models for measuring reciprocal relationships between phonological awareness and beginning word reading, and between Approximate Number Sense (e.g. having a rough idea which picture has the most dots) and number knowledge.

569 Brisbane beginning readers’ skills were measured five times at six month intervals, and the data analysed. The results support a causal relationship between phonemic awareness and word reading in the early school years, but (surprisingly) not between Approximate Number Sense and number knowledge.

Aotearoa/NZ Better Start Literacy Approach

Prof Gail Gillon of Canterbury University spoke about the implementation of the Better Start Literacy Approach with five-year-olds across Aotearoa/New Zealand. Both the World Health Organisation and the UN are calling for systems-wide action on literacy teaching. COVID-19 had profound adverse effects, especially for poorer kids. Advocacy for the science of reading across schools is critical.

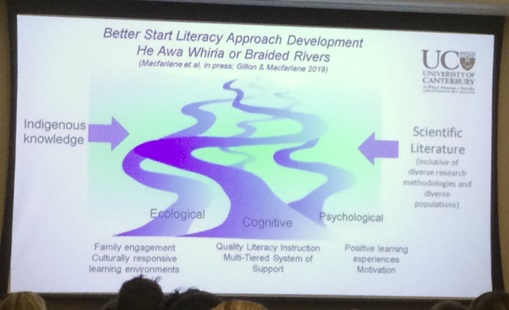

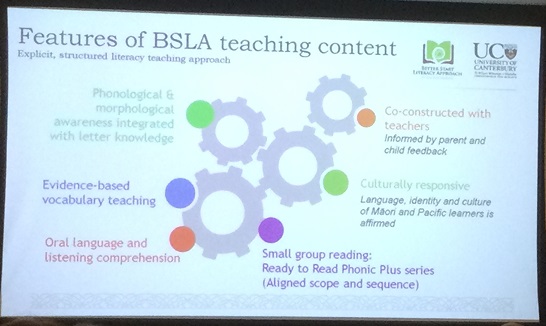

Better Start uses a “Braided Rivers” approach, taking into account indigenous and scientific knowledge, and has ecological, cognitive and psychological streams. Culturally responsive teaching practices and resources, positive learning experiences and family engagement are key in high deprivation contexts. A strengths-based approach is needed, with quality professional development, and online assessments adapted for children with special needs.

Better Start was developed between 2015 and 2019. Feedback from schools about its positive impact led to its national rollout commencing in 2020. It’s now used in more than 833 schools, especially in high deprivation areas. 36,500 teachers and literacy specialists have done Better Start online training, for which they are awarded a micro-credential. They are required to pass the course, which provides some quality control. The training is professionally-produced, with subtitled videos, and available to all professions.

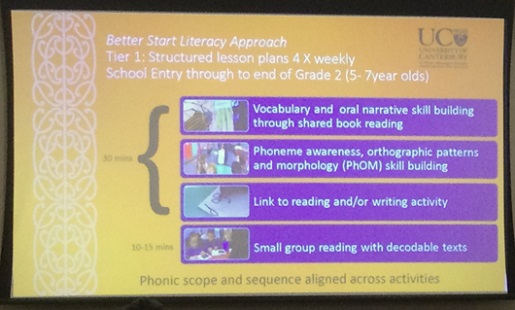

Tier 1 structured lesson plans are implemented four times weekly from school entry until the end of grade 2. See photo at right for the lesson components. They’ve developed and provide culturally relevant Ready To Read Phonic Plus readers, plus there are some free online readers.

In the first 10 weeks of the program, Tier 1 of Better Start aimed for 30 minute lessons per day. Most teachers managed this, with 80+% including all key lesson components.

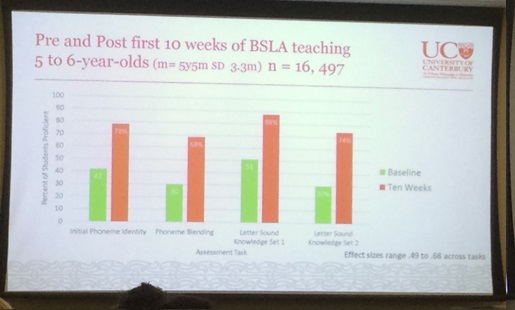

In one research cohort, 28% of children could identify initial phonemes at school entry. After 10 weeks of teaching, this rose to 72%. About 20% of kids could blend phonemes at school entry, but 57% after 10 weeks of teaching. Children from Maori and Pacific Islander backgrounds began with lower skills, but caught up with peers.

Children start school on their fifth birthday in Aotearoa/NZ, so teachers are used to scaffolding/differentiating to support new children, and this is a key part of the Better Start program. Schools are now usually choosing between Reading Recovery and Better Start. Reading Recovery is in decline, with only 41% of schools, whereas 46% of schools are now doing Better Start.

Phonemic Proficiency and word reading skills

Dr David Kilpatrick from the State University of New York at Cortland has been working with the WIAT-IV test developer and a statistician on a timed Phonemic Proficiency subtest involving phonemic manipulation. Remembering written words requires rapid and automatic access to their sound structure, in order to link sound to print.

Pseudoword decoding subtest results were the strongest predictor of performance on word-level reading subtests and the oral reading fluency test, though phonemic proficiency scores added some validity for ages 12-17.

Set for Variability: relationship to word complexity and grade/age

Set for Variability (SfV) is the ability to figure out a word’s actual pronunciation from the way it’s said when it’s decoded (the “spelling pronunciation”). SfV is a robust predictor reading skills.

When children start learning to read words with more than one syllable, they have to contend with unstressed syllables, syllable boundaries, and words with prefixes and suffixes, all of which can make decoding words harder. If one pronunciation doesn’t make sense, the child has to try another pronunciation. It’s a mystery why some kids do this easily, and others don’t.

A/Prof Laura Steacy of the Florida Centre for Reading Research discussed studies with school beginners and grades 2-5 students which examined how well SfV predicted word reading skill. SfV was more important for the older children, which might be related to having had experience of reading instruction. The transparency of words also made a difference.

She said there were three main developmental hypotheses about SfV:

- It’s highly related to phonological processing, through the process of phonological clean-up.

- It’s a metalinguistic skill, and significantly overlaps with phonemic awareness and vocabulary.

- It captures dynamic changes in word reading, and has a bidirectional relationship with word reading.

The results of the studies A/Prof Steacy discussed tend to support hypothesis 3.

I’m not sure I’ve done this paper justice, so if you have questions, please ask lsteacy@fcrr.org.

Pronunciation correction and Set for Variability

Mispronunciation Correction Tasks (MCTs) are used to evaluate a reader’s Set for Variability, and are strongly correlated with polysyllable word recognition. Most polysyllable words contain something, usually a vowel, needing phonological cleanup (e.g. changed stress).

A/Prof Devin Kearns of the University of Connecticut’s research explored whether this is because SfV gives the reader access to a word’s phonology and semantics, or whether orthographic information plays a greater role.

When children sound out a word incorrectly, they can correct it by trying (a) different sound(s), or using knowledge of vocabulary and/or phonotactics/orthotactics (permissible sound/letter sequences). Kearns developed an Incorrect Pronunciation Correction Task (IPCT) using words/pseudowords differing by one phoneme. The incorrect part of the mispronunciation had a different spelling from the target word (e.g. “planket” for blanket). Sometimes a sound’s manner was changed (e.g. a stop sound became a fricative), in others a sound’s place in the mouth was changed (e.g. alveolar to velar), and in others voicing was changed.

117 grade 3 and 4 children’s IPCT scores didn’t predict their word reading better than their MCT scores. This suggests SfV has an orthographic component, and that print and sound continue to interact in the process of decoding words. Item analysis showed kids could correct a word more easily if a sound’s manner changed (e.g. /t/ to /s/), rather than changing its place (/t/ to /p/) or voicing (/t/ to /d/).

Eye tracking evidence of mispronunciation correction

Eye movements give clues to cognitive processes during reading. The eyes fixate for longer, and look back more, at long, uncommon or unfamiliar words. Dr Lyndall Murray from Macquarie University explored whether kids’ eye movements suggest they are correcting mispronunciations as they read.

Four classes of Year 5 students were taught 16 novel spoken words used at ‘Professor Parsnip’s invention factory’. Each class learnt a different pronunciation of the words. For example, one class saw a picture of a contraption with an arm and a sponge for cleaning fishtanks, and were told it was called a ‘vake’. Another class was told it was called a ‘vike’. They then had to read the words, and a set of untrained words, in sentences that included contextual information e.g. ‘The fish in the dirty tank swam around the vaik as it worked’, and in neutral sentences. For the kids told it was a ‘vake’, the spelling of the word was considered regular. For the kids told the machine was a ‘vike’, the spelling was considered irregular.

The children’s eye movements, as well as their audible mispronunciation corrections, suggested that they were correcting mispronunciations when reading irregular words, even when reading silently. This research has been published here, if you’d like to find out more.

Targeted and explicit spelling teaching

Spelling is important for its own sake, but also in compositional writing, with 24-43% of the variance in NAPLAN writing data explained by spelling. It is more influential than grammar or punctuation.

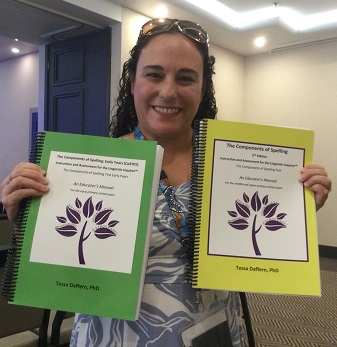

Dr Tessa Daffern of the University of Canberra researched the usefulness of spelling error analysis data in teaching spelling. A 10-week intervention study involved 572 Year 3-6 students in 31 classes across four schools.

Teachers from two schools participated in intensive professional learning about spelling informed by Triple Word Form Theory, which proposes that children draw on phonological, orthographic and morphological knowledge from when they first begin to learn to spell. These teachers then used spelling error analysis to plan and implement spelling instruction. Short, sharp, focussed teaching took 15-20 minutes per day. The intervention included spaced learning/review so there were opportunities to consolidate skills, handwriting activities, visible learning intentions and immediate, specific and ongoing feedback.

Teachers from the two other schools taught spelling in a ‘business as usual’ way, for about 30-60 minutes per week. Teaching was mostly via rote-learning and/or incidental phonics, although one teacher was interested in and knowledgeable about spelling, and used spelling error analysis to inform teaching. Two classes had no spelling instruction.

The intervention groups’ spelling improved significantly. Only one comparison class had significantly improved spelling: the one whose teacher used spelling error analysis to inform teaching (surprise, not).

More thoughts on Set for Variability

Professor Anne Castles from the new Australian Centre for the Advancement of Literacy at ACU was the discussant for the sessions about Set for Variability. She spoke about Carsten Elbro’s hypothesis that we store a ‘spelling pronunciation’ (how you’d sound a word out when first encountering it) for a word when we learn its printed form. It’s hard to test whether this is actually stored in the lexicon, or assembled on the fly by converting graphemes to phonemes, but that could be tested with timed tasks in the lab.

Lots of research on Set for Variability has been done on adults, but it’s hard to know how relevant this is to children, who have smaller vocabularies and less reading experience. However, it’s clear that Set for Variability is not just an oral language Thing.

Carsten Elbro pointed out that people who speak different variants of English can still talk to each other fluently. We aren’t phased when a New Zealander counts “one, two, three, four, five, sex”, because we’re aware of pronunciation differences, and also different word choices e.g. “lift” versus “elevator”. We can think of learning orthography as being similar to learning a dialect or variant of the language. What we try to learn is the dialect of orthography – a different sort of language that speaks from the book – so that we can ‘speak orthographic’.

The last five conference sessions I attended were all presented by researchers from La Trobe University’s Science of Language and Reading (SOLAR) lab.

Problematic ideas about the teaching of reading

Dr Nathaniel Swain from the SOLAR lab conducted a review of highly cited papers and reference books about the teaching of reading. He found that popular texts for teachers, such as The Next Step in Guided Reading, The Daily Five and Reading Strategies, often contain non-evidence-aligned ideas, and ideas that directly contradict scientific reading research e.g. three-cueing, guided reading, teaching a ‘range of reading strategies’, and teaching a love of/joy in reading rather than relevant skills. A common theme is hostility to systematic, explicit, teacher-led instruction.

It’s very concerning that such texts are still popular among teachers, and on reading lists for Initial Teacher Preparation courses. More research is needed into teacher beliefs and ideas which inform practice. Teacher-centred practice studies, research syntheses for teachers, and observational studies of classroom practice in research-aligned schools are also needed to bridge the gap between research and teacher professional discourse.

Teacher perspectives on reading comprehension

Reid Smith from the SOLAR lab and Ochre Education (an amazing Australian not-for-profit/free resource hub, created by and for teachers) wanted to find out what the average Australian upper primary school teacher knows and does about reading comprehension.

In early 2020 he used a web-based survey to collect data from 284 Australian primary school teachers. This was built on the Propositions About Reading Instruction Inventory (Rupley and Logan 1985), and asked about:

- teachers’ beliefs about reading comprehension.

- their instructional practices and apportionment of time to teaching reading comprehension.

- their use of commercial reading programs.

- how they gained their knowledge about reading instruction.

There didn’t seem to be a commonly agreed view of how reading comprehension develops, how to monitor progress, or what teaching should look like in practice. Teachers mixed and matched strategies into a real bricolage. About 40% reported a student-centred approach, another 40% were more content-centred, and some teachers were in both camps.

Assessment practices were also variable e.g. some teachers thought reading for enjoyment was a good measure of reading comprehension. Only 3.7% of teachers said their pre-service education was where they got their knowledge about reading comprehension instruction. 5.3% said they got their knowledge from reading coaches, and 42% from their own research. About two thirds of schools had commercial programs, but there was a lack of coherence between Tiers.

There seems to be no clear and common set of beliefs and practices that underpin reading comprehension instruction in Australian schools. A journal article about this research can be found here.

Running records

Running Records are widely used to assess children’s reading, though they’re steeped in discredited ideas, concerns have long been expressed about their validity and reliability, and they have very little empirical support. A/Prof Tanya Serry from the SOLAR lab conducted semi-structured interviews with 24 teachers and 16 education academics about the utility of Running Records, and analysed the data for common themes.

Three teachers and four academics thought Running Records were valuable in describing children’s reading progress, and guiding ongoing instruction. 16 teachers and 12 academics opposed the continued use of Running Records because of their association with discredited ideas about reading, flawed psychometric properties and poor objectivity. However, some people had no idea what else to use.

More work is needed to ensure theoretically sound reading assessments are used instead of Running Records in Australian schools.

Literacy interventions for struggling adolescents

10-30% of adolescent students are unable to access the secondary school curriculum because they can’t read well enough. They’re in every secondary classroom, and under-achieve at school, and long-term. Many secondary teachers don’t have access to the evidence about how to close the literacy gap between these students and their peers, and there’s limited policy direction to guide them.

Melanie Henry from the SOLAR lab, who also works with education research and consulting group Learning First, conducted an umbrella review of evidence available to teachers of teens with poor literacy. She synthesised 10 review articles, coding literacy intervention, primary studies, setting, agent, group size, dosage, social validity (or the kids won’t show up and the teachers won’t do it), maintenance effects/longevity of skill improvement, findings and recommendations for practice.

She found huge gaps in the research. It suggested that older students need 1:1 teaching, but it was hard to draw conclusions about other things. She will now conduct a qualitative study with secondary teachers to find out about current intervention practices in schools.

Higher education students’ literacy skills

Literacy proficiency is required for academic success in higher education. About 40% of Australian secondary students are struggling according to PISA, and their skills have been declining over time. 50% of Australian secondary students now go on to higher education. It’s to be expected that some students in higher education are struggling with literacy.

Emina McLean of the SOLAR lab conducted an online survey and follow-up semi-structured interviews with university education academics about the literacy skills of tertiary students. She found that academics are concerned, especially about writing, and note a decline in skills over time. Undergraduates’ skills are worse than postgraduates’ skills. Of the 17 academics interviewed, most said students are not arriving ready for the reading and writing requirements of higher education.

And that’s a wrap! Sorry there aren’t many photos, I planned to take more at the conference dinner on the last night, but fell ill. It was a great conference, and if anyone can think of a good excuse for me to go to Denmark for the next one, even though I’m not a reading researcher, I’m all ears.

Society for the Scientific Study of Reading conference: Day 2

0 RepliesThanks for the nice feedback about my SSSR conference Day 1 blog post, it’s helped motivate this one. Here are summaries of what I attended on the second day (any errors/misunderstandings are my own).

Neural deficits in dyslexia

Dr Tracy Centanni of the university of Florida talked about two genes on Chromosome 6 – KIAA0319 and DCDC2 – which are widely studied in dyslexia. If you suppress KIAA039, the left temporal area of the brain starts working inconsistently, either too fast or too slow. About 50% of kids with dyslexia have low neural consistency. This makes it harder to link speech sounds to letters.

DCDC2 is linked with white matter integrity in the language network, and helps neurons go where they should. Suppression of this gene in rats really messed with the speed of their performance, so perhaps this gene is linked to Rapid Automatised Naming (RAN), vital for fluent reading.

The most common neural deficit in dyslexia is low activation in the visual word form area (VWFA) in the left side of the brain. In non-literate people this area processes information about things like tools, faces and structures. Once learning to read begins, VWFA cells start to specialise in processing written words, linking the visual and language areas of the brain. Face processing gets partly shunted to the right side of the brain, but most people don’t notice they’ve lost half their face processing real estate. Even before dyslexic kids start school, their VWFAs respond less strongly to letters, but not nonsense objects.

Goals targeting writing skills in ASD kids’ IEPs

The Autism Spectrum is very diverse, and kids with ASD vary greatly in their literacy and broader educational needs. 70% of ASD students in the US have an Individualised Educational Program (IEP).

A/Prof Matt Zajic of Columbia University surveyed families of 954 ASD kids with an average age of 10, 80% of whom were male, and 60% of whom spent more than half their time in mainstream school. 80% had good cognitive skills, 89% had language disorder, 43% had ADHD. The survey asked whether the students had at least one IEP goal targeting handwriting, keyboarding, spelling, grammar, punctuation, or sentence/paragraph construction, but didn’t evaluate the quality, quantity or priority of these goals.

Data were analysed using Latent Class Analysis, a statistical method used to identify hidden subgroups. About 15% of kids, mostly younger ones, fell into a transcription subgroup (handwriting and spelling). 17% of kids, mostly older ones, fell into a text generation subgroup (sentence and/or paragraph construction).

About 24% had ‘most needs’, and 44% had ‘minimal needs’, which I think means 44% of kids were good at writing and 24% were seriously not, but that could be wrong, he was going very fast. Keyboarding goals were low across the board. Cognitive, language and/or attention diagnoses didn’t make much difference to the data, but grade, time spent in mainstream school and adaptive behaviour did make a difference. More research is needed on different profiles, relationship to reading goals and level of professional support.

TOPsy: the Test of Prosody via Syllable Emphasis

There’s a clear link between prosody (speech intonation/stress patterns) and reading in research. While we know prosody is important for communication, it’s poorly understood. Dr Srishti Nayak of Vanderbilt University Medical Centre has been working on a test of adult prosody. It takes 10 minutes, and has 28 items. Test words are said by a female American English speaker, and test-takers identify word stress.

However, Dr Nayak pronounces many of the test words differently from the test, because she speaks Indian English, so she doesn’t do very well on her own test. The TOPsy is thus quite accent specific, and how it might work in other languages is not clear, since some languages have mobile lexical stress (e.g. English, as in ‘PHOto’ but ‘phoTOGrapher’), while in other languages (e.g. French) lexical stress is fixed, or operates in other ways.

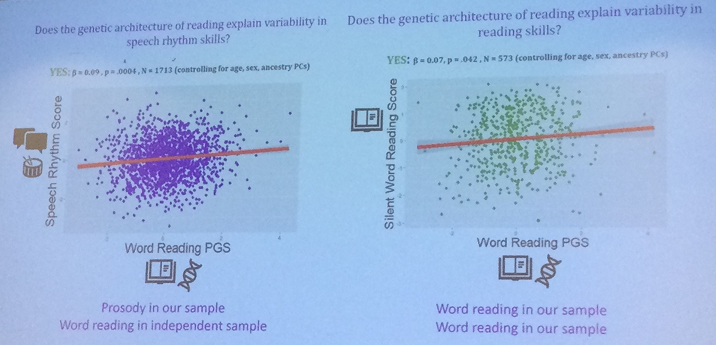

The TOPsy built on an existing internet-based silent reading fluency test from Hong Kong called WordSword. This presents digital text without spaces between words. Test-takers have four minutes to mark word boundaries. The TOPsy also drew on a large genetic association study of word reading, to combine prosody scores with measures of genetic predisposition for reading. I didn’t really understand how, so write to Dr Nayak if you’re curious.

Anyway, the lower your prosody score on the TOPsy, the more likely you are to have dyslexia. There was also a genetic association between prosody and reading. People being studied provided genetic material by mailing back saliva kits during the pandemic. Researchers are creative!

Reading skills and the digital divide

47% of kids living in poverty in the US lack high-speed internet. Research in North Carolina compared broadband speed and state reading test scores, and found a small but significant increase in scores thanks to faster broadband.

Dr Callie Little of the Florida Center for Reading Research examined the impact of pre-pandemic (2015-2017) broadband access on early reading nationally. Data were from 650 children involved in the National Project on Achievement in Twins, aged 5 to 8 years, 89% of whom were white. Parents ranked internet speeds from 1-5, and average download speed in megabytes per second in each census tract was also collected. The Child Opportunity Index is also organised by census tract, and rates opportunity from 1-100 based on educational, health, environmental and socio-economic factors. DIBELS composite scores were used to measure reading. Number of devices in the home were not measured.

No significant association between internet access and early reading achievement was found in this study. Broadband speed information for 2020 is now available, so researchers will look at the impact of COVID-19 on reading achievement, including for older kids who had to do more homework online.

UFLI foundations: an affordable, evidence-based Tier 1 program

Dr Holly Lane talked about the University of Florida Literacy Intervention (UFLI) Foundations program, which was developed over two years in response to school requests to improve phonics outcomes. University staff had been giving schools program-agnostic professional learning advice, assuming this would lead to improved instruction, and thus to better student outcomes.

However, they discovered that professional learning improves teachers’ knowledge, but their practice doesn’t change. Teachers also need an educative curriculum. So the university staff asked, “What if we just develop the lesson plans for you?”. Schools said “yes, please!”.

UFLI scope and sequence and lesson plans were developed to be very explicit and systematic, with lesson routines, many opportunities to practice, interleaving, the development of automaticity, progress monitoring and differentiation. UFLI was piloted in one school with 16 teachers in the first year, then usability and feasibility revisions were made e.g. they discovered word chains need to be provided, as teachers are more likely to skip them than make up their own.

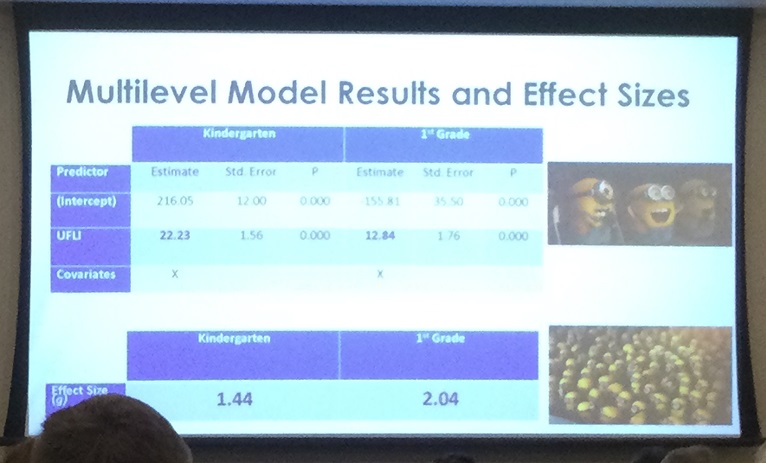

In the second year they did a district-wide pilot, with 1670 students in Years K-1, and measured progress with DIBELS (8th edition). The comparison groups were children at the same levels in the previous year. School autonomy presented a problem in implementation, as not every teacher implemented UFLI with fidelity, and this was related to outcomes. However, Effect Sizes for UFLI were still remarkable: 1.44 for Kindergarten and 2.04 for Year 1 (an Effect Size of 0.8 is considered high).

In the US summer of 2022, UFLI Foundations was released. Each lesson plan is two pages, and the only other things teachers need are letter sets, markers, whiteboards and free stuff from an online toolbox e.g. decodable text, a slide deck, web-based apps, and printables. They are still adding to these resources. UFLI is thus very cost-effective to implement, you just need the book.

UFLI has now gone viral, about 180,000 teachers around the world are using it, and Dr Lane has just toured Australia (darnit, I was busy with other things and missed her).

Teacher-led Tier 2 in Aotearoa/NZ’s Better Start Literacy approach

Associate Dean Brigid McNeill of Canterbury University talked about the Better Start Literacy Approach‘s Tier 2 (small group, helping beginners keep up) intervention. This needs to be:

- Explicit and systematic across all Big Five domains of phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency and comprehension.

- Complementary/supplementary to classroom instruction (Tier 1), but providing more intensity and exposure.

- Implemented early, and then building towards evaluation.

The Better Start program is strengths-based, and includes online teacher professional learning completed whenever suits them, and resulting in a microcredential. Facilitators are paired with teachers, to provide coaching and mentoring. There is family engagement and culturally appropriate resources. Online monitoring assessments identify kids with difficulties, monitor learning, help with planning, and are adapted for children with complex needs.

Better Start is now in 833 schools across NZ, and 3650 teachers have been trained. Over 43,000 students have been involved, 23.4% Maori, 9.4 Pasifika, 12.4% Asian and 46.8% European. 14% of children involved have had tier 2 support.

The Ready To Read Phonic Plus series readers, which were co-constructed with teachers and informed by parent and child feedback, are used. There are some scripted lessons, and some that teachers develop.

Children have baseline assessment at school entry, then 10 weeks later any strugglers start Tier 2 intervention for 20 weeks, focusing on phonemic awareness, phonics and word decoding/encoding. The gap between the Tier 2 children and other children disappeared at 30 weeks on all measures except their scores on reading connected text, where controls reached a higher level, perhaps because they could process text faster.

Key aspects of this research were that it took a co-creation/partnership approach, had high stakeholder engagement, and quality professional learning and development delivered at scale, with in-context, ongoing support. Evaluation of impact was via teacher administered measures and integrated into the study design, and teachers could use their evaluations to drive teaching decisions.

Stay tuned for more on Better Start’s Tier 1, discussed on Day 3 of the conference. There’s also a Tier 3.

The slow development of fast word recognition

Most children get better at recognising both written and spoken words in their first few school years. To understand what we hear and read, we must identify words efficiently. Spoken words are presented temporally in fractions of a second, but when reading, we must rapidly tell the difference between words with shared letters, by building evidence for the correct word, and suppressing competitor words.

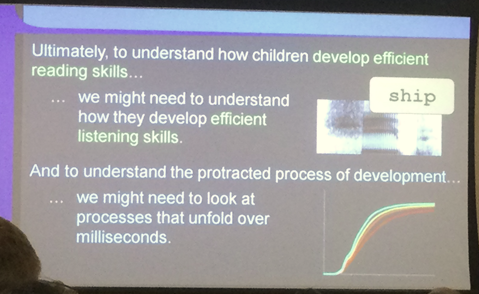

Professor Bob McMurray of the University of Iowa talked about research in which 280 children in Grades 1-3 saw briefly presented words and then had to click on matching pictures. Some of the competing pictures represented words with shared letters e.g. for the word ‘ship’, pictures were ‘shin’, ‘chip’, ‘shop’, ‘snip’ and ‘coin’. They also had to identify spoken words, but I didn’t write down how that was done, sorry. Write to him if you need to know.

There were concurrent relationships between spoken and written word identification, which suggest a common factor. More robust and efficient spoken word recognition leads more efficient written word recognition. Efficient spoken word recognition might reflect better phonological processing (discerning the structure of spoken words). To understand how children become efficient readers, we might need to better understand how they become efficient listeners.

The words children see and hear

Dr Luan Li of East China Normal University spoke about research into lexical variability (diversity in words used) in language seen and heard by school-aged children in China. Most research in this area has focussed on preschoolers, but in the early school years there is a vocabulary spurt, and it is a critical period for the development of abstract ideas.

Vocabulary diversity was studied in three sources of language input: child-directed speech (1.8 million words), animated cartoons/movies (1.8 million words), and picture books (1.5 million words). Picture books had the most diverse vocabulary, but cartoons/movies had greater contextual and semantic diversity, i.e. they used words in a wider variety of ways/to express more varied meanings. Child-directed speech had the least variability. The words kids see and hear affect language and reading development. If you can read Chinese, more information is here.

DIBELS 8th edition as a dyslexia screener

Most US states now require students to be screened for dyslexia, but there aren’t any screening tests specifically validated for this purpose (I hope EarlyBird will help fill this niche). Dr Patrick Kennedy from the University of Oregon spoke about outcomes of the first two of four years of research into the use of a general reading screening test – DIBELS 8 – as a dyslexia screener.

Preliminary results suggest that DIBELS can be used as a dyslexia screener, though it’s difficult to decide exactly where to put cutoff scores (e.g. 5th, 15th or 25th percentile).

Computer-adaptive reading screening

Dr Emily Farris from Middle Tennessee State University talked about research comparing three computer-based reading screening tests: Istation Indicators of Progress Early Reading, MAP-Reading and Star Reading. Third graders’ results on these screening tests were compared with the state achievement test, which 55% of children currently fail.

Sadly, none of the computer-based screeners were very sensitive or specific, they all identified far too many kids. These results suggest it’s probably not a good idea to rely on a single measure to identify children at risk. Screening in third grade is also too late, it needs to be done much earlier.

Compensating readers

Dr Kristina Breaux from educational publisher Pearson, developer of the widely-used fourth edition of the Weschler Individual Achievement Test, spoke about students who seem to read within normal limits, but still find reading difficult, and are reluctant to do it. These kids have above-average listening comprehension (standard scores of 105+), below-average phonological processing and pseudoword reading (standard scores of 85 or lower), but real word reading in the average range (standard scores of 85-90+ across four word reading subtests).

The WIAT-4 standardisation sample of 1800 school-aged students suggests that 1-3% of students might be considered compensating readers.

The text-complexity leap between third and fourth grade

In the US, nearly two-thirds of 4th and 8th grade kids are not reading at grade level, but ‘grade level text’ is poorly defined. Text complexity in grade level text increases substantially between third and fourth grade (from Lexile 420 to 740, a 76% jump).

Dr David Paige of Northern Illinois University discussed work developing systems which would allow more fine-grained tracking of progress, and earlier foundational work, so there is a smoother transition to reading at a fourth-grade level. This is needed if most fourth graders are to succeed on their state tests. The systems he was discussing are US ones, so I didn’t understand all of it, sorry. There is an article here.

Awards, including Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award

The awards ceremony was the last event on Friday, and I didn’t write down all the award and recipient names because I assumed they’d be on the SSSR website Awards page after the conference. They’re not there yet, and a new SSSR website is being developed, so perhaps the update is going straight onto the new site, which should be available soon.

Charles Hulme (whose name I have been pronouncing ‘Hulm’ in my head for decades, but it’s ‘Hume’, gah) won the Distinguished Scientific Contributions award and gave a talk titled: “What we talk about when we talk about reading“. I can’t do this talk justice here, but wrote down a few things:

- Causes of problems like dyslexia and poor reading comprehension are theoretical statements, not real Things. They only exist in the context of a well-specified theory/model, developing out of correlations and operating forwards in time.

- Hulme has been trying to specify cognitive processes in learning to read which can be tested statistically. Famous statistician George Box said, “All models are wrong, but some models are useful”. William of Ockham (he of Ockham’s Razor) said “Plurality must never be posited without necessity”. Einstein said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” We look for the simplest way to explain available data.

- Path diagrams can be used to represent causal theories. Causes and consequences are linked with one-headed arrows. Understanding causes is essential for developing and evaluating interventions. Intervention studies allow us to test causal theories.

- There are at least three causal influences of individual differences in children’s ability to learn to decode: letter-sound knowledge, phoneme awareness (PA), and rapid automatised naming (RAN). The first two are the basis of the alphabetic principle. RAN seems to tap a separable mechanism concerned with the efficiency of retrieving names from visual inputs. Phonemic skills and letter knowledge should fairly clearly predict early reading, and affect each other.

- Hulme set out to prove that RAN wasn’t important, but the data did not agree. Alphanumeric RAN after three months of reading instruction predicted the later rate of growth in reading over two years (Lervag and Hulme 2009). RAN repurposes neural mechanisms meant for other tasks in left-hemisphere brain region networks. Changes in the volume of the arcuate fasciculus (a bundle of nerves connecting language and frontal areas of the brain) predicted reading. RAN taps the left-hemisphere naming system, so having effective connections between posterior and frontal areas seems essential for fluent reading.

- The three components of the Triple Foundation Model (PA, phonics, RAN) all centre on aspects of phonology. RAN seems to tap some neurally constrained processes for retrieving the names of printed items. RAN seems to operate more strongly in later stages of development. We can’t train it, so can’t be sure it’s causal, but it probably is (he said, reluctantly).

- The Simple View of Reading (SVoR) is a statistical model of the concurrent predictors of reading comprehension. There are four potential profiles: typical readers, hyperlexia, dyslexia and language disorder/poor comprehension. Word reading and language comprehension should both predict reading comprehension, and they do. They have double-headed arrows between them in path diagrams, indicating a reciprocal relationship.

- The Wellcome Language and Reading study was a seven year study. Hulme thought speech skills at age three-and-a-half would be critical for the development of reading ability. He was wrong. Language development strongly predicts RAN, phonics knowledge and phonological skills. Word-level literacy at five-and-a-half tells you a lot about reading comprehension at age eight. All this is in line with the SVoR. But language skills are critical for the development of phonological skills. Phonology grows out of much broader, language-based skills.

- However, persistent speech difficulties are related to reading problems. One study of 569 kids starting school followed them for four years, and 7% had speech difficulties. These were a powerful predictor of later reading difficulty. The development of PA and Letter Sound Knowledge (LSK) are affected by persistent speech problems, a clear risk factor for later decoding problems. It’s easy to identify kids with speech problems.

- The Wellcome study provided strong support for the SVoR, but makes it more complicated as language and phonology are highly correlated, not independent. But the simplicity of the SVoR makes it helpful.

- Code-related skills drive decoding which influences comprehension. We also have a direct effect from language to reading comprehension. Early language skills provide the foundation for both decoding and comprehension.

- The Nuffield Early Language Intervention (NELI) improves narrative, vocabulary and listening skills. There have now been several randomised controlled trials of the effects of this intervention. Teaching assistants deliver this pullout program targeting the bottom 20-25% of kids. It produces reliable improvements in kids’ oral language skills. Children who got intervention strongly changed their language post-test scores compared with kids on the waiting list (the difference was 0.8 of a Standard Deviation, which is A Lot). In their second year of school, the intervention kids had improved language, and this completely accounted for improvements in reading comprehension.

- A mobile app called Language Screen has been developed, which operates on an Apple or Android tablet or phone. It has four subtests and is an easy, automated way to assess kids’ language ability. Thanks to UK Education department funding the NELI program has now been provided to 100,000+ children and data on well over half a million kids is being assessed with Language Screen. They also have a preschool language enrichment program which runs for 20 weeks, which kids and teachers like, and which improves language skills by a quarter of a standard deviation at population level.

- However, there are still lots of people selling snake oil interventions that don’t have good evidence.

- The title of this talk was inspired by a rather pessimistic short story by Raymond Carver called “What we talk about when we talk about love”, which is a story about what love means. There’s much more reason for optimism in the field of reading difficulties!

Society for the Scientific Study of Reading conference: Day 1

0 RepliesMy head nearly exploded with new learning at the Society for the Scientific Study of Reading Conference in Port Douglas last week. I wasn’t tempted to wag any sessions by beach, pool, sunshine or opportunities to chat, and often wished I could clone myself and go to two or three concurrent sessions.

I’ll try to summarise the most interesting bits, without getting too TL,DR. Any mistakes/misunderstandings in what follows are my fault, let me know if you spot one. I’ll write about one day at a time, or my brain really will explode.

Learning to read syllables

Danish Professor Carsten Elbro (co-author of Understanding and Teaching Reading Comprehension) described research in which adults learnt novel symbols for three phonemes (/m/, /s/ and /ar/, the latter not occurring in Danish). Surprisingly, dyslexic adults couldn’t blend two of these sounds into syllables, though they could say the syllables. Blending is very hard for some people. Perhaps this relates to the way sounds change when they blur together in words (coarticulation).

In Italy, fairly straightforward sound-letter relationships and relatively few possible syllables allow kids to be taught sound-letter relationships, after which most can figure out blending on their own. However, languages like English and Danish have complex relationships between sounds and letters, and greater complexity and number of possible syllables. Prof Elbro studied 200 Danish and Italian children in Grades 1 and 2, and found that learning to read new syllables was something that had a protracted influence on decoding development, especially in Danish. This may present lasting obstacles for learners in blending and retaining (via orthographic mapping) the pronunciations and spellings of syllables, so they can be read instantly in words.

Prof Elbro’s research found that showing kids how to blend by moving letter cards together was a waste of time. The kids who didn’t have this ‘blending support’ did equally well.

Orthographic skeletons

Readers who hear short, novel words create ‘orthographic skeletons‘ for them by thinking about how they’re probably spelt. Esra Ataman of Macquarie University’s Masters thesis research taught 81 adults made-up, spoken (but not written) words with suffixes like ‘vished’, ‘visher’, ‘jafed’ and ‘jafer’. These “inventions of Professor Parsnip” were used in sentences e.g. a ‘visher’ is a toaster-like machine used for shuffling cards. The adults were then asked to read the made-up base words e.g. ‘vish’ (expected spelling) and ‘jayf’ (weird spelling, you’d expect ‘jafe’ or ‘jaif’) and their reaction times were recorded. Weird spellings were read more slowly, suggesting the adults had formed orthographic skeletons for the made-up base words, even though they’d never heard them without suffixes. Whether the trained words had inflectional or derivational suffixes didn’t seem to make much difference.

Morphology meta-analysis

Dr Danielle Colenbrander from the recently-established Australian Centre for the Advancement of Literacy at ACU reported on a meta-analysis of research about teaching children how words are made up of meaningful word parts (morphology). Findings suggested morphology instruction helps kids with word-level reading and spelling, and transfers to the spelling of new words, but doesn’t affect comprehension. Only four of the 27 mostly US/UK studies included in this research studied beginning readers (K-2) so we don’t really know how early to start. Explicit teaching and longer-term intervention seemed to be better than implicit or short-term teaching, but there was great diversity and many gaps in the research, making it hard to know what kind of teaching is most effective, who benefits the most, or draw other conclusions.

Morphemes as islands of regularity

Dr Elisabetta Simone from Macquarie University compared how suffixes work in English and Italian. English has less complicated morphology than Italian, but much more complicated sound-spelling relationships. Her research added suffixes to real and nonsense words, and measured how quickly samples of 60 speakers of each language decided whether they were real words or not. The results suggested that English speakers relied more on morphological processing than the Italian speakers. Perhaps in the crazy chaos of the English writing system, standard spellings of morphemes provide helpful islands of regularity.

A hangover is not an overhang

Jasmine Spencer from Macquarie University spoke about the position of morphemes in written words. Free morphemes (words in their own right) can occupy different positions in longer words: ‘book’ is at the start of ‘bookshelf’ but the end of ‘textbook’. Even when compound words are scrambled e.g. ‘proofweather’ and ‘childrengrand’, they still look like real words. However, prefixes and suffixes are position-dependent. When they’re out of order – ‘ismtru’ or ‘ismsch’ – they look like gibberish. The 90 adults in her research took longer to reject scrambled compound words when their meanings were suggested by the component words (e.g. dreamday) than when they were not (e.g. linedead), and quicker to reject scrambled non-compounds (e.g. shadeday), so semantics plays a role in processing these written words. Subjects also rejected nonwords more slowly when they had real suffixes.

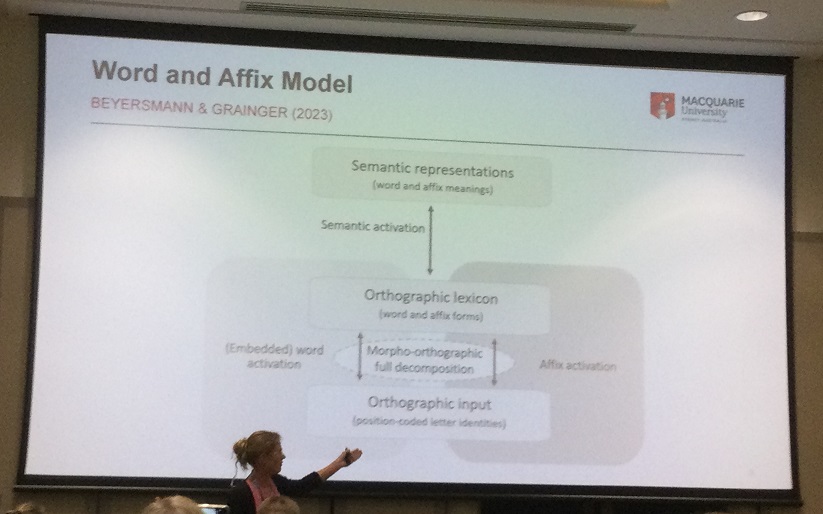

The Word and Affix Model

Dr Lisi Beyersmann from Macquarie University talked about a new model showing word parts being processed separately during reading. This is based on research showing typical readers read complex non-words containing real morphemes more easily than similar looking non-words. Research involving five adults with acquired dyslexia also showed they benefited from the presence of identifiable morphemes when reading nonwords. Even though prefixes come first in words, stems facilitated non-word reading more. This might be because stems tend to have clearer meanings, whereas affixes tend to be more abstract.

Tween/teen processing of morphemes

Leah Zimmermann from the University of Iowa spoke about research examining automatic processing of morphemes in 80 monolingual 12-14 year olds of varying reading ability. Students’ reading accuracy and automaticity (words presented for 90 milliseconds) were both tested on a set of 320 words. Half the words had only one morpheme, and half had two morphemes (stem and derivational suffix). Automaticity was important for fluency and comprehension, but the role of morphological processing was less clear. My notes say that the only variable to contribute unique variance to comprehension was the ability to read syllables, but I can’t find that in the abstract, so I hope it’s correct.

Spelling irregular words

Most English word spellings follow sound (phonological) or word part (morphological) logic, but some don’t. There’s growing interest in how to teach these, for example using ‘spelling pronunciations’ or repeated practice. A/Prof Saskia Kohnen from Macquarie Uni talked about a study of 14 children aged 8-11 who were poor spellers (5th percentile on the Test of Written Spelling) but had other skills in the average range. They did pre-tests, then two and six weeks later wrote out 182 irregular words from the Oxford Word List, to gather two baselines. There wasn’t much natural spelling improvement in between. They then did four weeks of training (direct copying, delayed copying, spelling to dictation) at home on 32 of the words, then did a post-test.

All 14 kids made significant gains on trained words. Eight also significantly improved on untrained words. Words containing only minor errors were more likely to improve, along with words high in frequency and neighbourhood size (with similar sounds/spellings). Improved spelling of untrained words might mean kids were using a different strategy, or improving their ability to represent words in long-term memory.

Lexical richness: the vocabulary of books

The language of books is quite different from the language we use in everyday conversation. Books tend to use more sophisticated words, and unique word types. Reading aloud to children gives them early exposure to this language, or access to greater ‘lexical richness’. Nicola Dawson and colleagues from Oxford University read 180 children aged 4-7 three versions of specially-written stories. One version used a basic vocabulary item (e.g. ‘hungry’) several times, another used several synonyms (e.g. ‘hungry’, ‘starving’, ‘peckish’, ‘famished’), and a third version used the most sophisticated word (e.g. ‘famished’) repeatedly. Children were asked to retell the stories to see which words they used. Children who heard the sophisticated words repeatedly were more likely to use them. Diversity was less important. There was a clear benefit from re-reading the stories. They are still collecting data on retention/use of synonyms.

Executive Functions training

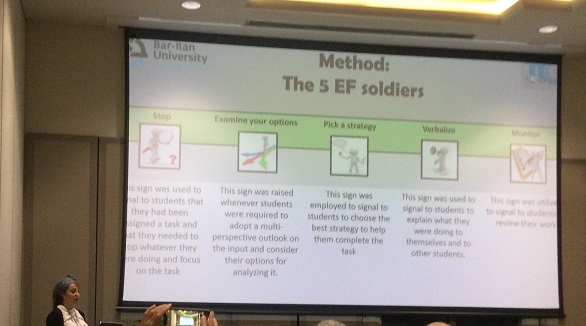

Working memory, attention, cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control – known collectively as Executive Functions – affect all learning. Shani Levy-Shimon from Israel’s Bar-Ilan University studied 72 Hebrew-speaking third grade poor readers, who worked in small groups of 3-4 students, for 35 minutes, three times a week for 16 weeks. 6 teachers each taught 2-3 groups, using either a multicomponent literacy intervention or business as usual. Some of the multicomponent intervention included Executive Functions training. The children receiving the Executive Functions training outperformed the other groups on all measures.

Psychosocial wellbeing

There were quite a few talks about the psychosocial impacts of literacy skill development/failure, but I’d decided to focus on word-level reading and spelling, so missed most of them. However, I did plan to attend a talk by NZ Prof John Everatt about research following two samples of struggling readers in Years 4-6. One group of 57 students received morphology intervention from Speech-Language Pathologists, while a second group of 30 received this intervention from their classroom teacher. Both groups improved not only their vocabulary, morphological awareness, word reading, spelling and reading comprehension, but also their academic self-concept and self-efficacy.

With five talks per session, and no time in between, I was often running between rooms like a madwoman, so must have missed the start of this one, when (I think) A/Prof Alison Arrow of Canterbury Uni, a co-author of the original abstract, explained John couldn’t come, and she’d talk about her PhD research instead. She had studied three groups of about 20 middle school students, who were given morphological intervention – 30 minutes 4 times per week for 10 weeks (40 sessions), or 20-30 minutes across 20 weeks (40 sessions). Their literacy skills improved, with some improvements on psychosocial measures as well.

She also said difficulties in psychosocial development due to literacy difficulties can emerge within the first six weeks of schooling, or even earlier, and can be pervasive and compound as students progress through school. Kids with learning difficulties often blame themselves for failure, but attribute success to external factors. There’s some evidence psychosocial development is very stable, so giving these kids reading success is perhaps the best way to meet their psychosocial needs.

Brain scans and diagnostic terms

Kelly Mahaffy from the University of Connecticut talked about brain scans comparing typical readers and poor decoders with ‘poor comprehenders’. She said the latter group make up about 10% of the population, and have reduced vocabulary, and difficulties with semantic and syntactic processing, inference and comprehension monitoring. In a large sample from the Child Mind Institute Healthy Brain Network Biobank, there were some frontal lobe grey matter differences, but no significant difference in white matter. This suggests executive functions are important in reading comprehension.

After the session I asked her why she didn’t use the internationally-agreed term Developmental Language Disorder instead ‘Poor Comprehenders’. She said there are people who are good at both decoding and language comprehension, but poor at reading comprehension. I raised an eyebrow and said I’d never met one, and she said she’d send me more information. I’ll let you know if it’s interesting.

Poster displays

After lunch each day there were lots of poster displays. I won’t try to summarise them, or the interesting discussions they provoked, but here’s what they looked like:

Overhaul of Initial Teacher Education

0 RepliesI’ve been doing little happy dances about the announcement in the video below, and am celebrating with a two-week 20%-off-everything sale in the Spelfabet shop (use the coupon code HappyDance at the checkout):

An expert panel review has found that Australia’s universities aren’t preparing teachers to teach reading and writing well. Our Education Ministers say they must do better at this, and other areas like maths and classroom management, without delay. Teacher knowledge is the key to student success.

A lot of good work from many good people has achieved this, but there’s nothing so inspiring or persuasive as a good example. Schools in the Canberra-Goulburn diocese have retrained their teachers in the science of learning, and reduced NAPLAN reading underperformance from 42% to just 4%, with similar gains in writing and spelling. Read more about this here, and make sure your school leadership knows about their Catalyst program.

Researchers have known for a long time that this kind of success is possible, but it’s less well understood in schools and the wider community, and there are still barriers to its achievement needing dismantling. Education academics and others have already pushed back on the conclusions of the teacher education review, arguing that things like inequitable school funding and teacher workloads, wages, and status are the real problem.

I think it’s shocking that most government schools (which educate the most needy students) get less funding than they’re entitled to under the School Resource Standard, while private schools get more. This should be corrected, pronto, but it’s not an argument against improving teacher preparation. We need both funding fairness and excellent teacher preparation.

Teachers have to work harder when their classes include many kids who can’t read or write very well. Work must be differentiated. Too many kids who understandably hide their learning difficulties behind challenging behaviour must be prevented from distracting the whole class, and supervised in detention. This is not fair to either kids or teachers. It’s preventable.

Giving graduate teachers the skills to get most kids reading and writing well enough to participate and succeed in class should reduce teacher workloads. Success at important work tends to lead to job satisfaction, respect from others, and a sound argument for higher wages. None of the arguments I’ve heard against the ITE overhaul so far stack up.

I’m excited and happy-dancing for two other reasons:

Society for the Scientific Study of Reading conference

The international Society for the Scientific Study of Reading conference will be held in Australia (Port Douglas, ehem) later this month, and I’m going. Stay tuned for a blog post or three about it.

So many amazing people will contribute to the 22-page program, it’s hard to know which sessions to attend, or who to ask for a selfie, or what to focus on for the blog. If you’re coming too, please can we share notes?

Display of decodable books

After collecting decodable books and setting up ad hoc displays for years, we’ve finally set up a Proper Display of a range of decodables in our North Fitzroy office. Looking at things to buy online is just not the same as being able to pick them up and handle them yourself. We’re hoping our display will help local early years teachers successfully make the case, and obtain the funds, to replace their classroom’s predictable/repetitive texts with high-quality decodables.

My colleagues Elle Holloway and Georgina Ryan have been examining the books in detail, and writing summaries to help teachers evaluate the different options. Stay tuned for a blog post about how to book an appointment to browse the display, which currently looks like this:

Chances are your child’s school uses programs which lack strong evidence to support teaching: what parents should know

0 Replies

An article appeared in The Conversation last week called “Chances are your child’s school uses commercial programs to support teaching: what parents should know“.

At first I did a double-take. Parents should be aware, and very concerned, about the variable quality of literacy-teaching programs and approaches used in Australian schools. Many parents now know this, thanks to activism by parent, teacher and other professional groups, plus US journalist Emily Hanford’s brilliant reporting on what’s known generally as Balanced Literacy, and specifically programs by Marie Clay, Irene Fountas, Gay Su Pinnell and Lucy Caulkins.

Fountas and Pinnell’s Benchmark Assessment System and Classroom and Leveled Literacy Intervention programs, Caulkins’s Units of Study programs (all sold in Australia by Pearson), and other Balanced Literacy approaches (e.g. three-cueing, Running Records, Guided Reading, rote-memorisation of high-frequency wordlists), are widely used in Australia. A few Australian schools might still use Clay’s Reading Recovery program, despite recent research showing its long-term impact, and petitions like this one from my local Dyslexia Victoria Support (please sign if you’re in Victoria). Caulkins has now seen the scientific writing on the wall, and added systematic phonics to her early years program, but I’m not rushing out to buy it.

However, The Conversation’s authors last week, three Education academics from Edith Cowan University in WA, were not objecting to poor quality programs. They were objecting to commercial programs.

Are they just anti-commerce?

Are the authors anti-commerce in general? Do they grow their own food and make their own clothes, avoiding the stench of filthy lucre? Maybe they think all educational programs should be free. This would make writing programs the province of overworked teachers and the independently wealthy. Is earning a living writing educational programs wrong? Aren’t teachers entitled to the best available tools?

The article’s stated concern is that “the content and the way students are being taught is outsourced to a third-party provider, who is not your child’s teacher.” Interesting use of the passive tense. Outsourced by whom? Are they seriously suggesting that teachers should make, not buy, all programs? What about programs consistent with the best available scientific evidence, and extensively classroom-tested? Do they seriously think it’s OK for the nation’s children to be here’s-a-program-I-made-earlier guinea pigs?

Well, no. They write:

“It is easy to see why schools use commercial programs. They offer efficient, consistent delivery of content across year levels. They also save teachers planning time and come with ready-made resources for lessons.

But schools often adopt these programs to reduce workload or because they have become widely accepted by other schools, rather than investigating whether they are endorsed and peer-reviewed by Australian or international education experts.“

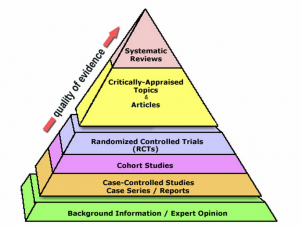

The evidence pyramid

I did another double-take. Programs “endorsed and peer-reviewed by experts” are the best schools can do?? But expert opinion is right at the bottom of the evidence pyramid. Sure, it’s better than nothing, but experts get stuff wrong all the time. We’re talking about the nation’s kiddies here. I respectfully submit that schools should focus on evidence from (ideally) the top of the evidence pyramid, much of which is readily accessible in plain-English explanations like this one from the Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation. We should all simply ignore experts when they disagree with the best available scientific evidence.

I’m sorry, but what exactly is being argued?

The Edith Cowan academics’ article goes on to argue against (strongly evidence-based) direct instruction because of “broad understanding” that play-based experiences are better. What exactly is “broad understanding”? Once upon a time, we had a broad understanding that the earth was flat.

It says using a commercial program limits a teacher’s ability to meet individual needs. I would have thought that not staying up all night writing programs, or having to think through every aspect of their delivery, would help rather than hinder a teacher’s ability to differentiate.

And then the old chestnut: commercial programs are “taking autonomy away from teachers, while devaluing their professional knowledge and skills”. Is teacher autonomy really a core value for parents? Do the authors realise that highly-valued, knowledgeable and skilled professionals like surgeons and engineers can’t just do what they like? They must keep their checklists and procedures strictly aligned with current research and best practice, lest they be sued for malpractice or build something that falls down and kills people. Yet they’re still highly valued.

The article says teachers receive evidence-based training at university. The 2021 report of the Quality Teacher Education Review disagreed, and recommended universities improve (among other things) what they teach about reading, including phonemic awareness and phonics as essential in the early years.

Like most unconvincing articles, this one wraps up with a grab bag of unsubstantiated claims: commercial programs are generic, repetitive, irrelevant, and make it hard for kids to learn “at their natural pace” (does this mean “let the slower kids go slow?” Surely that’s a recipe for letting them fall further behind?). They could harm engagement and social and emotional development. Hmm. Links provided are to very general articles about good practice, but no research highlighting the evils of commercial programs in schools.

Hooray for all the teachers who know better, and are doing better

The teachers I talk to are hungry for information about evidence-based practice, and determined to be accountable to their students and the wider community. They’re joining groups like Reading Science in Schools in droves, and booking out Sharing Best Practice and ResearchEd events. They’re critically evaluating the programs available in their schools, dumping poor-quality ones, and replacing them with better quality programs. Some of these are free, and some are bought with money (AKA commercial).

These teachers are amazing, parents should know about them, and we should all be cheering them on.