New year, same crappy old Education Department advice

20 Replies

In 2018, my state’s Department of Education and Training (DET) produced a brochure for parents called “Literacy and numeracy tips to help your child every day”.

Its top recommendation for “Helping your child work out difficult words” was to tell them, “Look at the picture. What word makes sense?”

Its authors clearly weren’t across the scientific research on how the brain learns to read, which shows that strong readers read (surprise!) the written words in books. Guessing words from pictures or context is only the strategy of 1. weak readers, and 2. learners trying to read books containing spelling patterns they’ve never been taught (e.g. predictable texts, still sadly widely used in schools).

I wrote a cranky blog post about the DET brochure at the time. Then, as my hands were still itching to tear my hair out, I made a free phonics workbook with the same teaching sequence as affordable decodable books, to give parents without much cash a better alternative.

Three years later, parents of five-year-olds have once again been given the same crappy advice in the same brochure, in the 2022 Prep bags. This is the Australian state with the car number-plate slogan “The Education State“, I kid you not.

The brochure only contains the word ‘phonics’ in a section called “Making the most of screen time”, but doesn’t help parents find quality early literacy programs, or consider the difference between them and Reading Eggs, as I have here and here.

There are five nice story books in the Prep bags, suitable for parents to read to children, but not a single decodable book suitable for young beginners to read themselves (unless the book “Hark, It’s Me, Ruby Lee!” is different from “It’s Me, Ruby Lee!” in the Education Minister’s media release).

For a calm, thorough discussion of the difference between the approach recommended by the DET in this brochure, and the approach recommended by reading scientists, see this article: Balanced Literacy or Systematic Reading Instruction? by Prof Pamela Snow.

There has been lots of media discussion about the importance of evidence-based teaching in the early years – recent examples are here, here, and here – and so many wonderful schools and teachers are enthusiastically embracing reading science, that I’d imagined further taxpayer-funded distribution of bad advice to parents wasn’t possible.

Our system not only fails many children with language-based learning difficulties at the start of their education, it bizarrely offers non-evidence-based “Colour Themes” during NAPLAN tests, and this year is making life even harder for the ones who battle on to Year 12, by adding a literacy assessment to the General Achievement Test. The result will be recorded on their graduating certificate for potential employers to see.

Instead of going back to tearing my hair out, I’ve made my January 2019 free Letters and Sounds workbook available again. If you can afford something better, use it instead. If not, and if your child is being taught to read and spell by memorising and guessing words, I hope it helps get them decoding and encoding. The leaflet size Pocket Rockets follow the same phonics teaching sequence, and I think they’re still the cheapest printed decodable books for beginners around.

I look forward to the day when the Victorian DET provides more solidly evidence-based early literacy information and resources to children and parents.

Telling the Spelfabet story

3 Replies

You might have seen the recent, excellent guest posts on La Trobe University academic Emina McLean’s blog by teachers, telling their stories about discovering the science of reading. If you haven’t read them, her blog is here, and the posts so far are:

- Keep the balance, Sheryl, keep the balance (Sheryl Ferlito)

- Knowledge is Power (Brooke Wardana)

- This is personal (anonymous)

- My long journey towards the science of reading (Shaun Killian)

- I was told to immerse the child in print (Julie Mavlian)

- Seeing the light (anonymous)

Emina also writes about what research shows does and doesn’t work in getting people to change their minds and their practice, which is pretty consistent with one of my favourite YouTube videos:

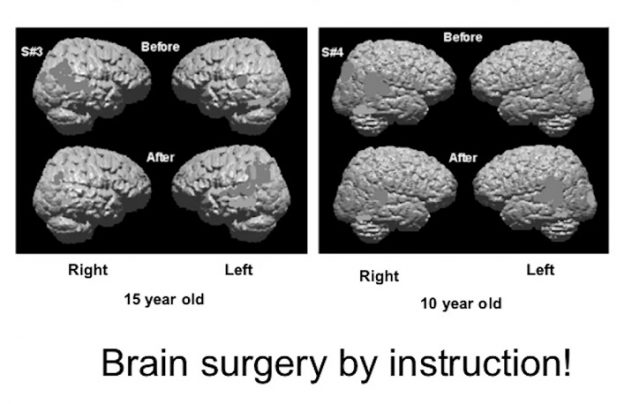

Since stories are more powerful than facts, I’ve decided to have a go at communicating my Spelfabet story: realising a lot of my clients couldn’t read because they hadn’t been systematically and explicitly taught to decode/encode words, teaching them successfully and setting up my website to share this knowledge and related strategies, resources and research.

Instead of a blog post, I have made a nearly nine minute (yeek! Too long! But it’s hard to cut back) video, which is now on my website home page. I hope it helps encourage others to also share their stories and connect with each other in a No-Shame zone, realising that we’ve all made mistakes and missed opportunities, are all always doing our best, and that (as the good folk at the US Reading League say) when we know better, we do better. Here it is:

Thanks to Emina for her excellent, strategic insight (she might still be looking for guest posts if you have an inspiring story you’d like to tell!), her storytellers, and also to former colleague Nicole Erlich who bought me the book “The Influential Mind” a few years ago, and I didn’t pay as much attention to it as I should have (another mea maxima culpa, I’m not even a Catholic, sigh).

We’re still in COVID-19 Stage 4 lockdown here in Melbourne, but had only 14 new cases today (huzzah!) so fingers and toes crossed the end is in sight. Stay well!

THRASS: the phonics of Whole Language

35 Replies

People often ask my opinion of the THRASS (Teaching Handwriting, Reading and Spelling Skills) approach, which has long been used in many Australian schools. Till now I’ve mostly replied that I’m no expert on it, but I’m yet to see robust research evidence supporting it, and aspects of it have never made enough sense to me to invest in the training.

I once worked at a school in a tiny room where lots of THRASS resources gathered dust. Two huge, laminated THRASS wall charts kept overwhelming their blu-tack and falling on my head.

I looked through the resources, but was working mostly with kids with language disorder or intellectual disability, and they would have been overwhelmed by wordy, THRASS-chart-based spelling explanations like this or this (cognitive load!). The THRASS graphemes kit was too big for our room’s tiny table, and lacked example words and some of the graphemes I wanted, so I made my own.

I tried using a THRASS board game but found it a bit incomprehensible. I don’t like teaching program-specific jargon, like “phoneme fists” or “grapheme catch-alls”, and rapping THRASS chart words might be fun, but I’m not sure why else you’d do it. (more…)

The Phonics Patch on ABC iView

25 Replies

Someone recently asked me why I’m not a fan of the phonics English mini-lessons on ABC iView. They seem to me to demonstrate what American Public Media journalist Emily Hanford calls “The Phonics Patch”. Rather than designing a literacy-beginners curriculum to systematically and explicitly teach sound-letter relationships to automaticity, a Whole Language/meaning-first teaching approach is supplemented with a few phonics activities, and rebadged as Balanced Literacy.

Title and learning intention

The title of ABC iView’s mini-lesson 16 (you’ll find it here if you scroll down: https://iview.abc.net.au/show/mini-lessons-english) is “Decoding words by segmenting individual sounds”. But segmenting is what we do to spoken words, in order to spell them. When you’re decoding, you start from written words, and must figure out the sounds and blend (not segment) them. So the title doesn’t really make sense.

The stated learning intention is to break words into individual sounds to read them. This makes about as much sense as the title. Is the learning intention talking about spoken words, or written words? It’s hard to know.

This is a systemic problem

The teacher in the video seems like a nice woman whose students probably adore her, and who teaches phonics in the way that many teachers have been taught to teach it. Typical initial teacher education courses focus on language meaning and don’t teach teachers much about the language structure which is the basis of our writing system (sounds, spelling patterns, meaningful word parts), so unless teachers learn this during a placement at a school with strong phonics teaching, or do inservice training after graduation, it’s hard for the typical teacher to teach phonics well.

This problem is systemic, and both teachers and students are being badly let down by the system. So please don’t interpret any of the following as personal criticism of the lovely, otherwise-skilled teacher in the video, or teachers generally. As the good folk at the US Reading League say, when we know better, we do better.

There seems to be no phonics teaching sequence

The video introduces children to three important words: segmenting, blending and digraphs. But saying you’re going to teach “blending” is a bit like saying you’re going to teach “riding”. Riding what? A skateboard? A bicycle? A horse? Two-sound words like ‘in’, ‘up’ and ‘at’ are a lot easier to blend and segment than four or five sound words like “stop” or “slips”, and English syllables can have up to seven sounds.

Which digraphs will be taught? English has dozens, it’s not possible to teach them all at once. It’s hard to figure out where the teaching in this video might fit into a systematic phonics teaching sequence.

Precise sounds and precise language matter

The teacher in the video sits at a whiteboard with plastic letters and nice Elkonin boxes on it, but the very first sound she says is mispronounced. She says “PUH” not a crisp, voiceless /p/. When teachers say consonant sounds sloppily/with additional vowel sounds, they make blending difficult for young children, as instead of blending /p/, /i/, /g/ they are blending puh-i-guh. When the video’s teacher blends, she doesn’t actually blend phonemes (p-i-g), she blends onset and rhyme (p-ig).

The teacher says “a digraph is two letters that make one sound”. Young children are literal creatures, so some will think this is literally true, and wonder if they should sit closer to the letters so they can hear them making sounds. Digraphs are two letters that represent one sound. I sometimes simplify this by telling young kids that sounds are invisible so we can’t really draw them, so we use letters to draw them instead. Using more accurate language makes for fewer confused children.

The teacher says that the first sound in the word “the” is voiceless /th/, which it isn’t. “The” starts with voiced /th/. I’m starting to wonder if this teacher has been taught what all the phonemes in our dialect of English are. Also, if this lesson is introducing the concept of digraphs, probably “th” (whether pronounced as in “then” or “thin”) is not the best one to start with, as lots of five-year-olds can’t say these sounds yet, or hear the difference between them and /f/ and /v/. That’s why they cutely say things like “Fank you” and “Can you help me wif vis?”.

How to spoil storytime

The next section of the video I found frankly bizarre. The teacher starts fluently reading a fun story book which contains two and three-syllable words, vowel digraphs and trigraphs, doubled consonants, contractions and other words that are hard for beginners. Then she randomly stops, just as the story is getting going, and pretends not to be able to read the word ‘stop’. She says “I’m stuck on a word. I’m going to segment (??) out the sounds, /s/, /t/, /o/, /p/, blend it together /st/, /op/, stop! Back up and reread…” and then she goes back to reading the story.

It turns out this teacher can fluently read almost all the words in the book, including the following quite hard words: believe, reason, simple, lose, quivering, loudly, Trevor, reply, ain’t, supper, faster, race, face, gobbled, biscuits, kibble, sausages, whoppers, munched, gnashing, choppers, swallowed, minute, something, know, guess, stuffing, notice, lucky, squeezed, tantrums, ceased, sometimes. She doesn’t notice that she misreads “wolfed” as “waffled”.

She pretends to get stuck on three more words, which she laboriously sounds out: stamp, thank, bin. These words are much easier than the many hard words she reads with ease. If any actual child read the way she does, they’d be a scientific curiosity. Is she trying to teach children that we only sound out easy words, and the hard ones you just have to know somehow? I counted 435 words in the story, and the teacher sounded out four of them. Is she trying to teach children that sounding-out is a relevant strategy for fewer than 1% of words?

If you like, you can try this embedded phonics strategy yourself next time you’re reading a lovely story to a young child. I very dare you. You’ll find that even polite, placid children will soon be giving you the “can you cut that out and just read the story?” evil eye. Highly recommended, if your jam is annoying kiddies and spoiling storytime.

If you’re teaching kids to blend sounds, then blend sounds (not bigger chunks)

Back at the whiteboard post-story, the teacher says we’re going to practise segmenting and blending, and to “get your mouth ready” (which is my suggestion for the subtitle of the Phonics Patch Movie, what does it even mean?). She says /p/ and most other sounds correctly this time (yay), but the words she’s chosen to study from the story are a mixture of levels of difficulty. Where C= consonant and V= vowel, they are a CVC, a CCVC, and two CVCC words, one of which includes a digraph. So if the kids can only manage three-sound words, the last three words are too hard, and if the kids can do four sound words, the first one is too easy. The digraph in the last word is a new one (ch), though children have had no chance yet to practice the first digraph she taught.

When the teacher blends the four-sound words, she does it by saying the onset then the rime, not by blending the individual sounds, i.e. she’s not blending /s/, /t/, /o/, /p/, she’s blending /st/ and /op/. She blends “best” as /b/, /est/ and “champ” as /ch/, /amp/. For kids with poor phonemic awareness, this will be mighty confusing. Where did “op” and “est” and “amp” come from? They weren’t the sounds she said.

A puppet sequence at the end of the video has the teacher saying individual sounds to read words, but then blending onsets and rimes, or for the word “munch” she says /m/, /un/, /ch/, but then having blended the /n/ with the vowel, she segments it out again to get “much”, and has to self-correct. At the end of this sequence we have yet another new digraph, “sh”, again before kids have had a chance to practise the ones taught earlier.

……

Will any five-year-olds learn how to blend or segment from watching this video? Will they be able to read or spell more words, including perhaps words with digraphs? Highly unlikely.

That might not matter to you if you’re used to teaching early reading via multicueing, repetitive texts, and rote-memorisation of high-frequency wordlists with an occasional phonics patch, or if you think getting 85% of children reading well enough is something to celebrate, as a PETAA spokesperson recently said. Or if you have no knowledge or experience of really powerful, effective phonics teaching.

ABC iView Learn A Word

25 Replies

I don’t know who advises our national broadcaster on the content of its early literacy education videos, but I find them pretty underwhelming.

Please don’t show children in your care the Learn A Word series on ABC iView. It teaches children to rote-memorise the appearance of words, recite letter names, and “take a photo with your eyes” of words.

The sounds in words (phonemes) aren’t even mentioned, though awareness of these sounds is the glue needed to make letters and written words stick in memory.

The Learn A Word videos first say “Let’s all learn a word” and a written word appears on the screen. The first word is “after”.

The video script goes like this:

“After. This word is after. Can you point your finger at the word after?

Now use that finger to write with me. Around and down, up and down, around and straight down, then across, from top to bottom then across. Start in the middle then back around, down, up and over. Ay eff tee ee ar. After. We did it! Let’s say it together. After!

Can you write it slowly? Ay eff tee ee ar. Can you say it quickly? Ay eff tee ee ar. Great work!

I can use it in a sentence: After lunch I like to read a book

Take a photo with your eyes and remember this word: After

You just learnt a word!”

Then there is a pause, a new word is presented (the next word is “again”) and the whole thing repeats with much the same script. Well, I haven’t watched them all, as that would make my head explode with frustration, but I’ve watched quite a few, and they’ve been highly repetitive.

Even one-syllable, entirely sound-outable words like “up”, “at”, “it”, “if”, “on”, “get”, “run” and “from” are given this treatment. So are words with common two-letters-for-one-sound (digraph) spellings, like “them”, “good”, “boy” and “say“. Nobody points out that two letters represent one sound in these words, because nobody even mentions sounds.

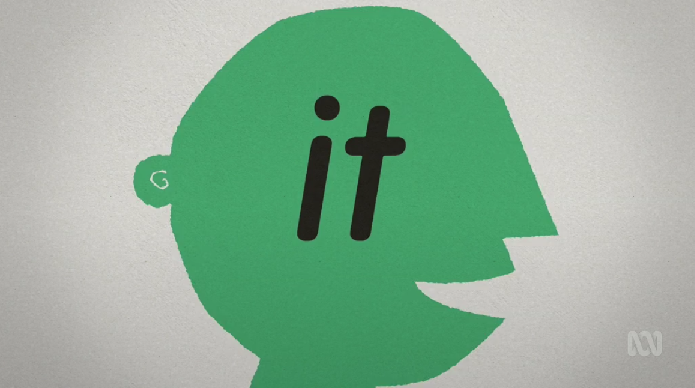

The videos explicitly encourage a visual whole-word-memorisation strategy, e.g. for the word “it”, the video says: “put it in your head and say it for when you need it. It comes in handy all the time. It is a great word. It.” Here’s how this is illustrated:

Occasionally children are encouraged to write words in the air, on their hands, arms, feet or the floor, very small or very big, very slowly or very fast. There’s music, pictures, and occasional giggling and sound effects.

Two-syllable words, and words with tricky spellings like the Greek-origin “ch” in “school” and the no-longer-pronounced Old English “w” in “two” get the same treatment. There’s no phonics teaching sequence, no patterns, nothing that would make sense to reading scientists, just rote visual memorisation, over and over.

I wish someone responsible for kids’ content at the ABC would read or listen to Emily Hanford’s reports, understand that a mountain of scientific research shows that we don’t learn to read by visually memorising words, and produce better content for Aussie kids. Maybe ABC presenter Dr Norman Swan can be asked to take this up, as he’s the patron of AUSPELD. Learn A Word on iView is simply not up to the ABC’s usual high standards.

Is Reading Eggs all it’s cracked up to be? (boom tish)

22 Replies

After my last blog post about the new Reading Eggs – Fast Phonics program, its activity that looked exactly like a Nessy activity suddenly got new graphics. Then someone asked me why I’m not a fan of the original Reading Eggs program when it includes a lot of phonics, so I decided to take another look.

With hundreds of new COVID-19 cases daily (yeek) and a new face-masks-in-public rule, my state is heading back into another protracted period of home-based learning, probably including lots of e-learning. I want children to use programs that maximise their chances of successfully learning to read and spell.

Is Reading Eggs from the ABC?

I used to think that Reading Eggs was owned by the Australian Broadcasting Commission, because it uses the ABC logo.

Incorrect. Reading Eggs is owned by a company called Blake e-learning. It uses the trusted ABC name and logo in Australia under a retail partnership with ABC Commercial. The Reading Eggs site visible outside Australia, https://readingeggs.com, has no ABC logo (it quickly redirects Australians to the Australian site).

The ABC Commercial website says, “As an iconic, trusted brand, we are the only Australian distributor equipped to maximise the rights and opportunities across all product categories to help drive your business.” As a member of Friends of the ABC I was pretty surprised at that.

How should early reading and spelling be taught?

Beginning readers/spellers need be told from the very start that spoken words are made of sounds, which we write with letters. This seems obvious to literate adults, but is not at all obvious to young children, or many older learners. I once told a smart, illiterate teenager who’d had ten years of Australian schooling this fact, and he asked: “Why didn’t anyone tell me that?” (if you don’t know why, read journalist Emily Hanford’s reports or watch/listen to her recent PATTAN network talk here).

The sounds in our speech are invisible, quick and smoosh into each other, so splitting them up in order to spell them is hard. English is a mishmash of languages, warped over time (the wonderfully nerdy History of English podcast has details), so our writing system relates 44 speech sounds to 26 letters using five different types of logic:

- One sound can be written with one letter.

- One sound can be written with two, three or four letters e.g. sh, ou, dge, augh.

- Most sounds are written more than one way e.g. out, cow, drought.

- Some spellings represent more than one sound e.g. out, you, touch, cough, soul.

- Meaningful parts used to build longer words often have special spellings e.g. er, ed, ly, al, est, ous, chron.

Reading and spelling software for young beginners should stick to the simplest logic (#1). It should focus on teaching children to break up spoken words into sounds and write them with letters, and read words by saying a sound for each letter then blending the sounds together.

Like all good systematic, explicit, synthetic phonics programs (see examples) this software should start with just three to five sounds, represent them with single letters, and teach kids to use them to spell and read little words e.g. am, at, it, sat, sit, sis, mat and perhaps names like Sam, Sim, Tam and Tim.

Note that the words “is” and “as” don’t follow logic #1, as their last sound is /z/ (logic #4). Including them might confuse some children and undermine logic #1, so if they’re included they should be explained e.g. “at the end of words we often say /z/ for this letter”.

Extra sounds and their spellings should then be gradually, explicitly, systematically introduced and practised to mastery in short words (two or three sounds). Words can then be made longer e.g. with two consonants together as in “clip” and “tent”, then three as in “split” and “helps”, as consonant combinations can be quite hard to segment and blend.

This gives beginners a solid foundation for learning the additional sounds and remaining logic and patterns of our complex spelling system.

How does Reading Eggs stack up?

Reading Eggs offers a free trial period, so anyone can sign in and see the following things for themselves. It first introduces “the sound m, like in mouse” and presents the lower case letter m for children to click on to hear /m/ (I’ll put sounds in slash marks). There’s just letter m at first, and then children must discriminate it from two other letters. There’s no need to link sounds and letters in this activity, so it can be done using visual memory (not the kind of memory used in reading, see this blog post).

The program then asks “which picture starts with the /m/ sound?” and there are two pictures on screens e.g. “moss” and “sat”. I pretended to be a child without any awareness of sounds in words, and answered randomly. When I got it wrong, there was a “boing” sound with zigzags on the screens and I was told to “try again”. When I got it right, a cartoon character said a (less interesting) “yes”. No matter how many times I got it wrong, no help was offered. Eventually, thanks to having a 50-50 chance, I fluked it and went up to the next level.

I was then asked to “find /m/ in these words”, and printed words containing the letter “m” appeared the screen, but the words were not spoken, so again visual memory was all I needed. The words included digraphs (“moon”), split vowel digraphs (“time”) and two-syllable words (“metal”), examples of spelling logic #2 and #4.

When I clicked randomly I was told to “try again” till I eventually fluked enough correct answers. There was a song about words with “m” in them. The words flashed on screens with the letter m in a contrasting colour. To preliterate children, they probably look like chicken scratchings.

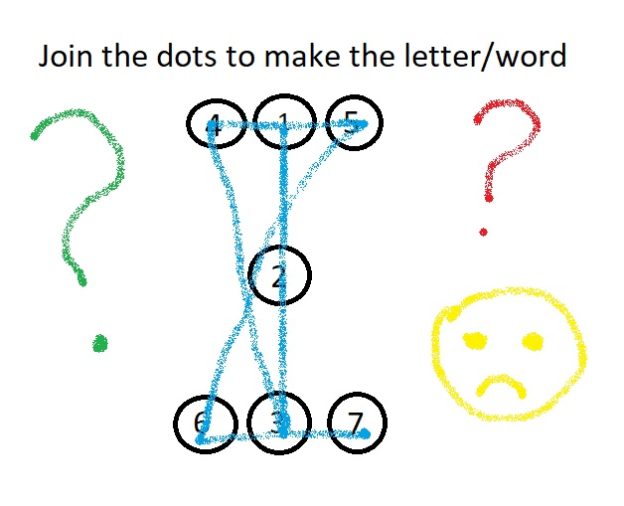

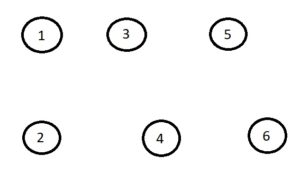

Next I was told to “complete the dot to dot to make the letter”, and there were numbered dots on the screen in roughly this layout:

I pretended I hadn’t learnt my numbers yet, and clicked randomly. I got three “boing” sounds and three red crosses on the screen, and then was asked “again?”. This happened no matter how many times I got it wrong. When I clicked on the dots in numerical order, the lower case letter “m” was filled in between the dots, and I was asked to do it faster. I hope a handwriting expert can tell us in the comments whether this sort of numbered-dot-clicking is a good way to teach early letter formation.

Next came a 6×6 letter grid with six copies of the letter “m” in it, in slightly different fonts, and including visually similar letters like “n”, “h” and “w”. I was told to click on /m/. When I made mistakes I got red crosses and “boing” sounds, and after three errors was asked “again?”, but the game did not adjust to my confusion by reducing the number of choices, providing hints or otherwise helping me.

I was then shown a letter “m” and told “This is the letter em, it makes the sound /m/’. Capital em looks like this (M), it also makes the sound /m/”. Preliterate me wondered why we have two letters for the same sound, but this wasn’t explained. A 6X6 grid like the previous one appeared, this time with capital letters, and again if I couldn’t find the M’s, the task was not simplified, I just went round and round being asked “again?” till I fluked it.

Next I was shown a letter “m” in a book and asked to click on the picture that begins with /m/. With only two pictures presented at a time, I had a 50-50 chance. The picture names were not spoken unless I clicked on the speakers next to them, and when I made three mistakes I had to go back to the start. There was no slowing down or stretching out of spoken words, or other explicit assistance with making the connection between the sound in words and the letter.

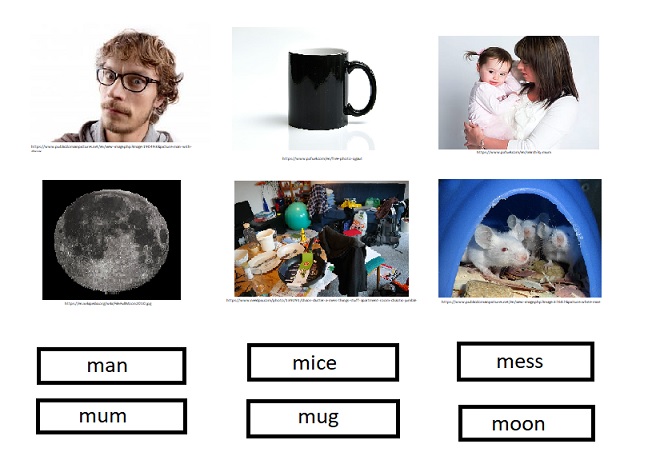

Next I was shown a screen arranged like this, and asked to drag the words to the pictures:

So far in this program kids have only learnt one letter, so can’t read the words, but that doesn’t matter because you just click on the words and they’re spoken, so all you need to do is match spoken words to pictures. You can just ignore the written words, and since reading them requires logic #2 (moon, mess, mice) and #3 (/s/ as in mess, mice), probably that’s a good thing.

Next there was a book with a different word starting with “m” on each page, including words with vowel and consonant digraphs, consonant blends and two syllables, and a total of 15 different sound-spelling relationships, some based on logic #2 (ey as in monkey and money, oo as in moon, ou and se as in mouse) and logic #4 (o as in money, monkey, mop; n as in man, monkey).

This type of book teaches preliterate kids to “read” by looking at first letters, pictures and guessing words. This is reading-like behaviour, but should never be confused with reading. So far only one sound has been taught, so kids aren’t yet equipped to start reading.

Next, the sound /s/ and letter “s” are introduced in much the same format. There is letter identification and matching, spoken word to picture matching (including the three-syllable word “spaghetti”), and a book about “s” with 23 different sound-spelling relationships involving logic #1, #2, #3 and #4.

In the third level I am invited to “Click on the word I” (my italics) and the capital letter “I” appears, first by itself and then with two other capital letters. Then I’m told I’ll be shown “the sound ‘am’ like in ‘clam'” (my italics). So this activity introduces two extra levels of word analysis – rimes (mislabeled sounds) and whole words. Preliterate me wondered why “I” is called a word, when it has only one letter, while “am” is called a sound, when it has two letters.

Next I was told to click on “am”, first by itself and then with distractor items like “xi” and “lu” on bowls of sugar cubes (Reading Eggs has also offered me cakes and marshmallows, so it’s not from the I Quit Sugar brigade).

Then I am asked to “click on the picture which has the am sound in it”, and pictures offered include “dam”, “ham” (which lots of people don’t eat), “lamb” and “stamp” (the latter being especially hard for little kids to discern the “am sound” in, as it’s not at the start or end of the word).

Then I’m shown the sentence “I am Sam” and asked to click on each word, after which the words are scrambled and I am asked to click on them again. Then I’m asked to “complete the dot to dot to make the letter”, though it doesn’t say which letter. It turns out to be a capital I. Preliterate me wonders why they’re now calling it a letter, not a word.

So far, Reading Eggs seems to be a mixture of initial, letter-of-the-week type phonics, picture-guessing and memorising whole words. In the next activity I’m asked to “say each sound and make the word” and shown how to blend “a” and “m” into “am”. This happens once only, and then I’m told “now it’s your turn”, and the visuals repeat, but not the sounds. The same thing happens for the word “Sam”. Then “a” and “s” (/s/) are blended to make “as” pronounced /az/. Nobody explains the sound change.

Next, lower case letter i is given its letter name (“I”), which you’ll recall was earlier taught as the “word” for upper case letter I. I’m asked to find six of them in a grid, but when I get to the grid I’m told to “click on /i/” (the “short” sound).

Sorry, but I really can’t justify spending any more of my time looking at a program that I am not going to recommend to anyone.

If you’d like my recommendations for early literacy iPad apps for little kids, see this blog post. Several of them have versions on other platforms, including Graphogame, Phonics Hero, Nessy and Reading Doctor.

Marketing reading science

7 Replies

I was glued, green-eyed to Twitter a couple of weeks ago for tweets about the US Reading League’s conference, wondering whether Greta Thunberg and the polar bears would forgive me if I planted 40 trees before I flew to their conference next year (global overheating freaks me out even more than education’s research-to-practice gap).

Excellent local linguist-teacher-blogger Lyn Stone attended the conference, and you can read her reports on it here: