Workshops comparing decodable books

18 Replies

Schools everywhere are replacing their predictable/repetitive texts for beginners/strugglers with decodable texts. Excellent. Kids need to practice decoding words, not guessing or rote-memorising them.

There’s been a recent market explosion of decodable books. I’ve just updated my website list, and discovered that the Reading League in the US has an even bigger list. My head is spinning. It would be very sad if people spent a lot of money on well-marketed, pretty, but pedagogically low-quality ones, then tried them out, didn’t like them, and went back to predictable/repetitive texts.

I’d like to be able to write a blog post giving my full and frank opinions about the range of decodables we have in the Spelfabet office. Well, maybe not the ones we keep at the bottom of the back cupboard. Unfortunately, we live in a litigious world, so I’d have to check such a blog post with a lawyer first.

However, I can invite locals to small workshops to have a Proper Look at these books, and discuss their features, advantages and disadvantages. After so much online learning and online shopping, that’d be a nice thing to do.

We’ve almost finished setting up our display of decodable books suitable for early years children in our workshops room, see photo above. My excellent colleagues Georgina Ryan and Elle Holloway have spent many hours preparing information sheets about each set of books, and I’m just finishing the task off.

I’ll be running a two-hour in-person, hands-on session about this display on Wednesday 22nd May from 1.30pm till 3.30pm, and more will be scheduled soon. Numbers are strictly limited to 20 people per session. If you work at a City of Yarra, Merri-Bek or Darebin school or local library (our local patch) please email info@spelfabet.com.au from your work address with the name of your school for a 50% discount code. Click here for a ticket.

We don’t have every available decodable book series, or full sets of every series, but once we’ve added a few new things, our early years display will include texts from:

- The Adventures of Doc Leeda (High Noon Books, US)

- Big Cat Phonics Practice, Big Cat Phonics for Letters and Sounds (Collins, UK)

- Bug Club/Phonics Bug (Pearson, UK)

- Core Knowledge Language Arts readers (free printables, US)

- Cracking the ABC Code (Aus).

- Dandelion Launchers, Readers and World (nonfiction) books (Phonic Books, UK and US)

- Decodable Jewels (Aus)

- Decodable Readers Australia (Early Readers, Main Fiction, nonfiction, Aus)

- Dog on a Log (Let’s Go Books, US)

- ERA Phonics Decodables (Aus)

- Fitzroy Readers (Fitzroy Program, Aus)

- Flyleaf Emergent Reader Series and Reading Series, (UK), which are also free online.

- Get Reading Right (Aus)

- InitiaLit readers (Multilit, Aus)

- Jolly Phonics (Jolly Learning, UK)

- Junior Learning Letters and Sounds sequence books (UK)

- Little Learners Love Literacy Pip and Tim, Wiz Kids, Tam and Pat and Big World (nonfiction) books

- Little Sprouts (High Noon books, US)

- Mog and Gom (Smart Kids, Aus? UK?)

- Phonics With Feeling (printable decodables, available from this website, Aus)

- PLD Literacy (other publishers’ books reorganised into PLD teaching sequence, Aus)

- Pocket Rockets (Smart Kids, Aus)

- Preschool University (printable decodables, US)

- Reading Elephant (download-and-print stories, US)

- Power Readers and Supercharged Readers (Voyager Sopris, US)

- Reading Mates (Aus)

- Reading Stars (Ransom, UK)

- Rip Rap Club (Cumquatmay, Aus)

- Rising Stars Reading Planet (Hodder, UK)

- Simple Words books (US)

- SmartKids Decodable Fiction Collection (Aus? UK?)

- Snappy Sounds (Macmillan, Aus)

- Sound Waves (Firefly Press, Aus)

- Sounds Write (UK)

- SPELD SA Phonic book series for Jolly Phonics sequence and Sounds-Write sequence (Aus)

- Sunshine books – Decodable series (Aus)

- UFLI Foundations (US)

- Whole Phonics (US)

We also have the No Nonsense Phonics kit (UK) and iPads with decodable books as apps, and a projector to show you a few cool online things, like the new Reading Doctor decodable texts (hilarious pictures are on the following page, so you CAN’T guess from them!). Please note that the workshops will be about decodable books for youngsters, not older, catch-up readers (8+ years to adult). We’ll need another whole session or two to discuss them. Let us know if that’s of interest.

If you’re local and want to attend, but can’t do so on Wednesday afternoons, let us know when would suit you at info@spelfabet.com.au. You might also like to try the Decodable Book Selectors from NSW SPELD.

Alison Clarke

Speech Pathologist

Dyslexia facts, myths and strategies

0 Replies

I’ve just listened to a great Ontario IDA Reading Road Trip podcast, in which the IDA’s Kate Winn interviews Dr Jack Fletcher about dyslexia facts, myths and strategies. Click here to listen to the whole thing yourself, and/or read the transcript, which includes references. For the time-poor and my own learning, here’s what I thought were key takeaways.

Defining and diagnosing dyslexia

Dyslexia is a word-level reading and spelling problem which results from a combination of biological and environmental factors. It’s a persistent inability to respond to the kind of explicit, intensive, instruction that works for most people.

Instructional response is the most important criterion for diagnosing anyone with a Specific Learning Disorder, especially dyslexia. Diagnosis should be based on multiple criteria, including progress monitoring measures from intervention, and norm-referenced achievement testing. Specialist dyslexia assessment tools aren’t helpful or necessary. Cognitive tests are only useful in identifying kids who are at risk in the first two years of schooling. After grade two, assessment should be focussed on academic measures of reading, spelling, and writing.

It’s not valid to diagnose dyslexia based on a discrepancy between cognitive skills and academic performance. Kids with reading problems with high and low IQs have the same difficulties with phonological awareness, rapid naming and so on. IQ tests have racial and social bias, so there are social justice issues associated with their use. A Pattern of Strengths And Weaknesses model is also a discrepancy model, is typically inaccurate and grossly under-identifies kids with learning disabilities. We also need to be aware of English Language Learners when identifying at-risk kids, so they’re not misidentified.

Related/co-occurring difficulties

Other kinds of learning disorders and difficulties often co-occur with dyslexia, such as problems with writing or mathematics. Kids with dyslexia often also have difficulties with attention and/or language needing separate intervention. Stimulant medication can help a child pay attention but it won’t teach them how to read. Learning to read words doesn’t guarantee you’ll know what they mean.

About 25% of kids with dyslexia have clinical levels of anxiety. Anxiety predicts a poorer response to intervention, so one US expert, Sharon Vaughn, has introduced five minutes of mindfulness meditation at the start of intervention sessions, to reduce anxiety.

Psychiatrist Shepherd Kellam studied an approach which prevented behaviour problems, but found this didn’t help kids improve their reading. So he introduced a reading intervention, and found that when they became better readers, the girls were less depressed and the boys were less disruptive. He also found that kids all knew who was struggling with reading, and that this was a source of anxiety.

Can dyslexia be prevented?

Many severe reading problems can be prevented if kids get the right kind of explicit instruction and reading experience in their first three years of schooling. About 40% of kids find it hard to learn to read well without really explicit and fairly intense instruction and early reading experience. This makes them aware of the sounds in spoken words and helps them grasp the idea that these sounds are what letters represent (the alphabetic principle) and develops their brains as mediators of reading. Early access to print gives the brain the kind of visual experience it needs to become an automatic reader.

If kids don’t learn to read in the first three years of schooling, it’s very hard for them fully develop their neural system and get the reading experience and vocabulary they need to become skilled, automatic readers. They can be taught to decode, but end up with persistent reading problems. Intervention in first and second grade is twice as effective as intervention after the third grade. It’s hard to differentiate reading problems due to biology and those which are due to environment. Brain scans of third grade poor readers who were not taught well and third grade poor readers at biological risk of dyslexia look the same.

Poor instruction is unfortunately still quite common, though teachers are not to blame, they always have good intentions. They just may not have the training and the knowledge that they need to be effective instructors for kids who are at risk. Improving and maintaining high-quality instruction, including classroom management, needs to be an ongoing priority.

What kind of intervention?

Explicit, systematic instruction in the general early years classroom works for everyone, but works twice as well for the at-risk kids (see this research by Barbara Foorman et al). There should be systematic, explicit phonics: teaching the relationship between what words sound like and what they look like. There should also be cumulative practice of skills to automaticity, and work on comprehension. Reading and writing strengths and weaknesses should be monitored, and intervention adjusted accordingly.

If you are including all these elements and collecting data towards your benchmark, and making good progress, then you should just continue until students achieve the benchmark.

Research by the late Carol Connor suggests decoding/word level intervention is about four times more effective in a small group (3 or 4 children per teacher) than a large group, as long as the groups are well matched and managed. This makes sense, as in phonics lessons, teachers have to listen closely to each child, and notice and correct their errors. There’s no evidence that individual phonics instruction is better than this kind of well-matched small group work (click here for information about upcoming Spelfabet holiday groups). The best indicator of which kids should be grouped together is their reading fluency.

Meaning-based instruction, on the other hand, can be done equally well in small or large groups. For English Language Learners, quality of instruction seems to make more difference than language of instruction.

Myths about dyslexia

Dyslexia is not a gift. The myth that people with dyslexia have special talents might result from individual differences and the natural orientation of development towards strengths.

People with dyslexia don’t see letters backwards. As we learn to read, we see mirror images of words in both sides of the brain, which gradually lateralises to the left side of the brain. This happens more slowly in people with dyslexia.

Other myths include: that coloured lenses or overlays help with reading; that dyslexia is a reading comprehension problem; that it’s rare; that people grow out of it; that Brain Training programs not involving reading instruction work; and that improving home literacy will overcome dyslexia. See the blue box on the right of Fletcher and Vaughn’s interesting article titled “Identifying and Teaching Students with Significant Reading Problems for the full list of 18 myths Dr Fletcher refers to in the podcast.

Thanks a quintillion to Kate Winn and Ontario IDA for this interesting podcast series, I’ll be going through the back catalogue in coming weeks, and just noticed a new 4 March 2024 episode pop up, with Australia’s own Dr Jennifer Buckingham. One for tomorrow’s morning dog walk, methinks.

Ten cheers for our new Children’s Laureate!

0 Replies

I was so excited to be invited to the launch of Sally Rippin’s two year program as Australian Children’s Laureate on Tuesday, though surprised to spot a former colleague in the crowd who was once staunchly anti-phonics and pro Reading Recovery/Fountas and Pinnell.

Then I realised: Sally is the Perzackly Perfect Person to cheer people off the sinking Balanced Literacy ship (especially since the Grattan Institute’s Reading Guarantee report), and onto ship Structured Literacy, so all kids can hurry up and start enjoying wonderful stories.

Sally isn’t just an author of great kids’ books, she’s the mum of a neurodivergent kid who struggled to read and spell, and a staunch advocate of making sure all kids are taught to crack our spelling code, instead of being encouraged to memorise and guess words. Her book for adults about this, Wild Things: how we learn to read, and what can happen if we don’t, should be in every school and local library. Here she is at the launch with queen of our activist dyslexia mums, Dyslexia Victoria Support founder Heidi Gregory.

Sally’s term as Children’s Laureate is the perfect time for a strong push to dump dross like predictable/repetitive texts and rote-memorisation of high frequency word lists, and promote things like decodable texts and systematic, explicit phonics teaching in Years F-2. It’s also the perfect time to improve early identification and intervention for neurodivergent kids in schools, and knock down barriers to reading for all kids.

The Grattan Institute report (there’s a podcast about it here, and a 20-minute YouTube summary here) says kids with poor literacy currently in school could cost taxpayers $40 billion over their lifetimes, not to mention the personal cost to those kids. I cannot think of a better use of my taxes than ensuring all schools use literacy-teaching methods that are based on the best available evidence, and that struggling and neurodiverse kids whose parents can’t afford high-quality private intervention don’t miss out on it.

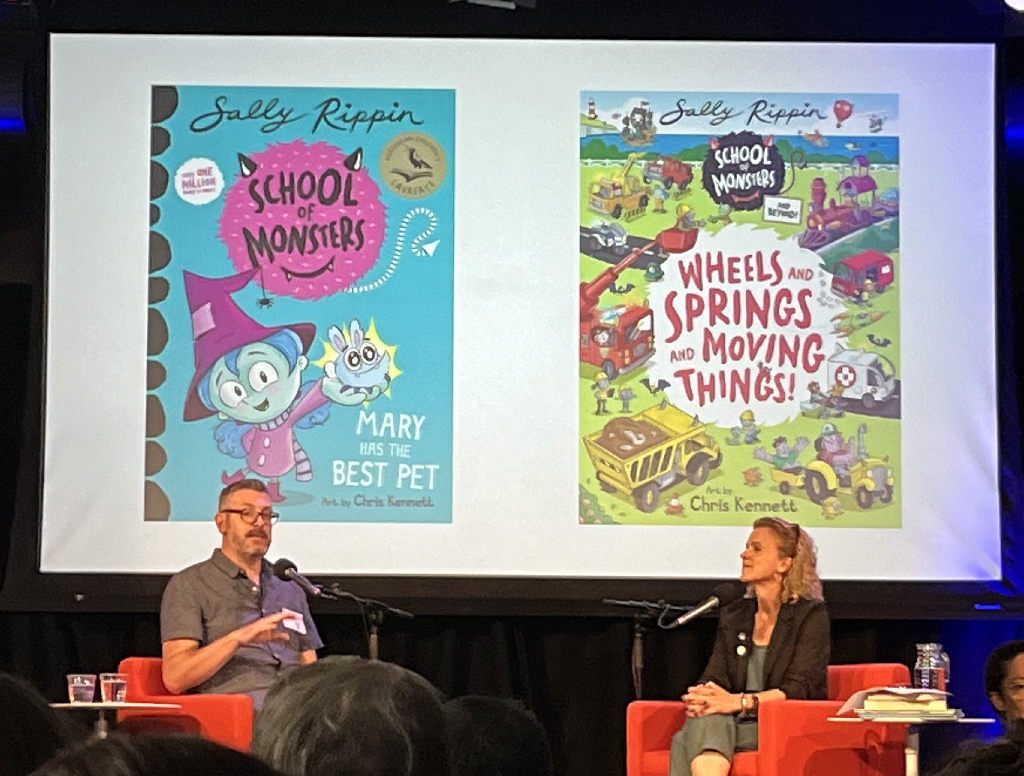

At the launch I also got a copy of Come Over To My House, a picture book co-authored by Eliza Hull, full of stories about making the world more accessible for everyone. It’s perfect for our waiting room. I also got some School Of Monsters compilations for our lending library, signed by Sally and illustrator Chris Kennett (who also drew little bats on them). Chris taught everyone at the launch how to draw a monster, which was rather hilarious.

Sally will be travelling all over Australia in the next two years, so make sure you find out when she is coming to a town or city near you (the ACLF newsletter and social media information is here), and spread the word. It’s a story well worth telling.

Benchmark Assessment: often wrong

0 RepliesIt’s the end of the school year in Australia, so children are getting their end-of-year reports.

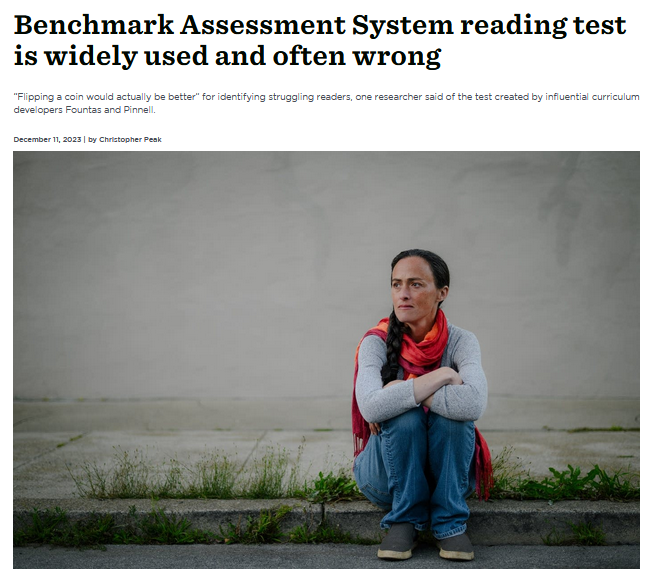

Many Australian schools use the American Fountas and Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System (BAS) to evaluate reading skills, but a new American Public Media (APM) report says it fails to identify most struggling readers.

If teachers rely on the BAS results, they will be advising many parents not to worry about their children’s reading skills, though there’s good reason to be concerned.

If you’re in this situation, please seek more reliable and valid assessment. Early intervention is highly effective, and ‘late bloomers’ are more likely to wilt and suffer than catch up.

There are plenty of more cost-effective, efficient, reliable, valid literacy skill assessments available for school use. The excellent, Australian Reading Science in Schools website has an assessment list you can download here. Chances are that teachers using the BAS don’t know about researchers’ adverse findings on it, or good alternatives. Do them a favour, send them the APM report and RSS assessment list.

If your school can’t provide valid, reliable reading/spelling assessment, try asking local Speech Pathologists, Educational and Developmental Psychologists or Specialist Educators for a second opinion. Very young kids can do quite a lot of learning in the summer holidays with good professional guidance and/or by attending programs like our holiday groups. The sooner they catch up with peers, the happier they’ll be in 2024.

Free & cheap word-building games

4 Replies

It’s the silly season, time to play more games. Excellent Spelfabet Speech Pathologists Georgina Ryan and Elle Holloway have devised and tested a set of download-and-print word-building card games which are now available in the Spelfabet shop. Each game can be printed on 3 sheets of A4 cardboard and handed to a group of kids to cut up and play, or you can laminate them first, if you want them to last.

The simplest game is free, and requires learners to add productive suffixes -ed and -ing, and Olden Days suffix -le (not used to produce new words any more, but still in heaps of words), to base words with ‘short’ vowels, adjacent consonants and the consonant spellings ss, sh, ck, ng, and tch. Here’s a video of how to play it:

Here’s a video of the other Initial Code game in the set, in which players add the suffixes -ed, -ing, -er, -y and -s/es to base words, doubling final consonants if required. If they have both -y and -er suffixes, they can stack these to create words like ‘bumpier’ and ‘jumpier’, changing -y into i before adding the -er.

Here are videos of two other games in the set, we hope this gives you the idea of how they work, and that they will work well with your learners. The whole set is available here. Happy silly season from all of us at Spelfabet!

Summer holiday groups at Spelfabet

0 Replies

Bookings are now open for our intensive explicit, systematic synthetic phonics therapy groups in the week of 15-19 January 2024.

These are for young children (in school Years F-2 in 2023) who need extra help with learning to read and spell words by sounding them out.

Each group will run for an hour a day, and include plenty of games and fun. We will provide daily homework to complete and bring to the next session.

The groups will be:

| Time | Skill level | Example words targeted |

| 8.45am to 9.45am | Beginners: VC and CVC words. | at, in, hop, bus, red, fan, big |

| 10.15am-11.15am | Adding common suffixes to base words, doubling final consonants as needed. Introducing three “long” vowels with consonant-e/split/silent final e spellings, and when to drop final e before adding a suffix. NB if you have a Year 3-4 child who needs this level of work, we may run a second group for them at 11.45am. | bat-batting, swim-swimmer, hop-hopped, run-runny, shade-shady, time, timer, hope, hoping |

| 11.45am to 12.45pm | Adjacent consonants: CVCC, CCVC, CCVCC, CCCVC, CVCCC. | help, list, trap, stop, crust, strip, jumps |

| 2.00pm to 3.00pm | Consonant digraphs. | wish, chat, fetch, this, when, quick, sing |

We will provide all the necessary resources, including specialist take-home readers. We have a maximum of four children per speech pathologist in our groups, to keep the pace/intensity high. We match children carefully and ask that everyone comes prepared to attend all sessions and do all the homework.

Our groups will be held at our North Fitzroy office in Melbourne’s inner north, with attendance by appointment only. Spaces are limited, and upfront payment for all group sessions is required to secure a child’s place. The cost of a week’s program is $720, which covers all sessions, materials and planning time, plus a brief final report with recommendations. Missed sessions are non-refundable. Private health rebates may apply, depending on your level/type of cover, but Medicare only provides rebates for individual therapy sessions.

Children not already known to us need to attend an assessment session with us before joining a group. This allows us to check whether we have a suitable group, and helps us cater for any special needs/interests. If we don’t have a group matching a child’s skills and needs, we can usually suggest other intervention options.

Please contact Tiana Knights on admin@spelfabet.com.au, (03) 8528 0138 or text 0434 902 249 if you’d like to find out more about these groups, or book an assessment for a struggling reader/speller.

Therapists’ duty of care means we must recommend evidence-based teaching

0 RepliesA local school leader recently contacted me ask that my colleagues and I delete one of the recommendations we often put in assessment reports, because it is prompting parents to question the school’s teaching approach.

The recommendation reads:

(Child name) should not be taught using a ‘whole language’ or ‘balanced literacy’ approach (Reading Recovery, Leveled Literacy Intervention, Guided Reading, PM Readers, Running Records, etc.) as this approach does not control adequately for word structure and phoneme-grapheme correspondences, and encourages the strategies of weak readers, such as guessing and rote-memorising words. This approach is not explicit or systematic enough in its teaching of sound-spelling relationships or word structure.

The school leader explained that her school system requires staff to use approaches we recommend against, so our reports were putting their Reading Recovery teachers and other staff in a difficult position.

We have no desire to put anyone in a difficult position, but our duty of care is to our clients. We must make recommendations which are in their best interests, based on the best available scientific evidence.

It’s completely unfair to a child to have one set of adults teaching them to sound words out, and another set of adults teaching them to memorise and guess words. Memorising and guessing words are the habits of weak readers, but are encouraged when high-frequency word lists are used as spelling lists, and children are given predictable/repetitive texts containing spelling patterns they’ve never been taught.

Undoing bad habits and building strong foundational skills is hard work, especially when we only see clients for 40 minutes once a week or fortnight. They’re at school five days per week. It would be professionally irresponsible not to tackle this issue in our reports.

I agreed to send the school leader evidence supporting our recommendation, but this is the second request of this type, so it probably won’t be the last. Answering the question in this blog post, and linking to it in our reports, should help parents argue kindly and clearly for science, and help school leaders learn about reading research, and discard programs and practices that don’t help children thrive.

Reading Recovery

- May et al (2023) Long-Term Impacts of Reading Recovery through 3rd and 4th Grade: A Regression Discontinuity Study found that Reading Recovery had a long-term a negative impact on children. There is also a plain-English article explaining this research here.

- The Centre for Educational Statistics and Evaluation’s (2015) Reading Recovery: A Sector-Wide Analysis showed children in Reading Recovery made modest, short-term improvements which weren’t maintained over time.

- The Pedagogy Non Grata website’s analysis of Reading Recovery is here.

- Five From Five (2019) Reading Recovery: A failed investment explains that Reading Recovery is a weak intervention because it fails to sufficiently target phonemic awareness and phonics.

Leveled Literacy Intervention (LLI)

- Research its authors call the independent, gold standard evidence for LLI received funding from the program’s publisher, and was published on a university website, not in a peer-reviewed journal. The valid, reliable, objective measure of progress used in this research – DIBELS – showed that LLI was not effective. Children only improved on the subjective, LLI-devised measure. Here’s a video explanation.

- Pedagogy Non Grata’s Effect-Size-based meta-analysis of LLI research is here, which concludes, “The program is not research based”. The author discusses this analysis in this video.

Fountas and Pinnell Classroom

- The Pedagogy Non Grata website’s analysis of F&P Classroom research is here, which concludes, “The mean effect size found was negligible”.

- Ed Reports’ 2020 evaluation of Fountas and Pinnell Classroom is here.

Other balanced literacy strategies/resources

- The Pedagogy Non Grata website’s analysis of Lucy Caulkins’ Units of Study is here.

- Pedagogy Non Grata found no peer reviewed research on balanced literacy.

- Prof Pamela Snow’s 2017 blog Balanced Literacy: An instructional bricolage that is neither fish nor fowl, says balanced literacy is poorly defined, and in practice means eclectic teaching.

- US Reading Panel expert Timothy Shanahan rejects Instructional Level Theory here. Edublogger Karen Vaites expands on this and provides research links here.

- The Five from Five website explains that levelled reading schemes’ books for beginners encourage word memorisation and guessing, the habits of poor readers, as they contain many words beginners can’t yet decode, e.g. this example from the PM Readers.

- The US Reading League has a Three Cueing Systems and Related Myths video lecture online.

- Articles by Dr Kerry Hempenstall about three-cueing/multicueing are here and here.

- A/Prof Dennis S Davis et al’s 2020 ITE-insider perspective on cueing systems called Is It Time for a Hard Conversation about Cueing Systems and Word Reading in Teacher Education? argues it’s time for educators to stop using cueing. Yes, please.

Science of Reading

- American Public Media journalist Emily Hanford’s* six years of reporting on this issue, including her podcast Sold a Story, can be found here. Recently interviewed in New Zealand, home of Reading Recovery (now rapidly being replaced by Better Start and other programs), Hanford said this:

- The Australian Education Resource Organisation website has an Introduction to the Science of Reading.

- Pedagogy Non Grata has done a meta-analysis of research on the science of reading and writing instruction, and has an easy-to-understand beginner’s guide to reading research.

- Prof Pamela Snow’s SOLAR: Science of Language and Reading article summarises the process of learning language and reading, and has a very useful reference list.

- US Edweek’s How Do Kids Learn to Read? What the Science Says video is a plain-English summary.

- Profs Castles, Rastle and Nation et al’s (2018) article Ending the Reading Wars: Reading Acquisition From Novice to Expert is another useful overview.

- Prof Stanislas Dehaene’s Reading in the Brain is a classic text, and his key ideas relevant to effective instruction from a 2023 talk are summarised here.

Switching to evidence-based teaching

- Prof Pam Snow wrote Leaving the Balanced Literacy habit behind: A theory of change in 2020.

- Pedagogy Non Grata has an article about the impact of the many US state laws targeting literacy here, and the author is interviewed about it here. Research shows 97.5% of children can be taught to read at grade level with the right core instruction, and intensity and type of intervention.

- US Teacher Crystal Lenhart wrote a great letter explaining to parents why her school made the switch away from Fountas and Pinnell reading levels, leveled readers, Guided Reading and three-cueing, towards science-based literacy teaching, which many other schools have used as a template. You can hear her discussing her school’s experience and her letter in episode 161 of the Melissa and Lori Love Literacy podcast, or watch it on YouTube.

- There’s now a massive teacher-led movement for evidence-based teaching in Australia – see Reading Science In Schools, Think Forward Educators and Sharing Best Practice. There is lots of useful information on the Literacy Hub, Five From Five, ULD for Parents and AUSPELD websites.

I hope leaders of Australian schools still using balanced literacy (an ill-defined mishmash of things that work, and things that don’t, some of which can be harmful) find the knowledge, resources and inspiration to switch to science based teaching of reading and spelling in 2024.

* No, Emily Hanford and Pedagogy Non Grata’s Nathaniel Hansford (who writes/speaks as Nate Joseph) are not related.

A Voice on First People’s literacy and more

0 Replies

Australians will soon vote on whether to recognise our First Peoples in our Constitution, and set up a permanent indigenous advisory committee (Voice) to Federal Parliament.

An estimated 40 per cent of indigenous Australian adults have minimal English literacy, and it can be as high as 70 per cent in many remote areas. According to Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) 2021 data, our Year 4 First Nations students scored 491 points on average, while students from other backgrounds averaged 547 points. It’s a similar, shameful story for most other indicators of wellbeing: First Nations Australians get a raw deal.

Respected indigenous leader and Senator Patrick Dodson explains some of the appalling back story, and the evolution of the referendum proposal, in this podcast. There’s a shorter video explaining the referendum here. No-one seems to be arguing against Constitutional recognition, but there is a campaign against an indigenous Voice to Parliament.

Some progressives, like Senator Lidia Thorpe, say the Voice will have no actual power, so governments will be able to ignore it if they don’t like its advice. That’s true. Within the limits of the Constitution, Parliament has the power to make, amend or repeal any law, and the Voice won’t change that.

Some conservative opponents argue the proposal is divisive and lacks detail, so “If you don’t know, vote no”. I’d rather finish the sentence, “If you don’t know” with “find out”. The Voice proposal is not about detail, it’s asking about an in-principle decision. Ballot papers will say: “A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?”.

Sadly, some opponents are saying things which are not true. It’s legal to spread campaign lies.

However, it seems clear that the majority of First Peoples support the Voice proposal, the first step in a process towards truth and treaty outlined in the Uluru Statement from the Heart. There’s been a surge of electoral enrolment in areas with high First Peoples populations. High-profile non-partisan First Nations people like Cathy Freeman and Michael Long, and most First Peoples organisations, seem to support a ‘yes’ vote.

I want to be an ally to First Nations people in their quest for educational and other justice, so I need to listen to the majority. If I pick and choose which First Nations opinions I listen to, I’m really just listening to myself.

Speech Pathology Australia, my professional association, has taken a stand on the upcoming referendum, saying, “Speech Pathology Australia stands with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities in favour of both the Voice and Treaty.”

In primary school, I made friends with Gunditjmara and Kirrae Whurrong artist Fiona Clarke. Victorians might have seen her public art in train stations and elsewhere, and if your Victorian school would like a colourful mural on a dull wall or water tank, please let her know. Her designs have also appeared on Australian Cricket Team outfits. I was delighted to catch up with her at a “Vote Yes” concert organised by her brother on the weekend, where we put our heads together to say this:

Why doesn’t NAPLAN start in Year 1?

0 Replies

It’s too late to find out a child is struggling to read and write in Year 3. The horse has bolted. It’s no longer possible to provide effective, cost-effective early intervention. Intervention is harder, less effective and more expensive. The damage done to a child’s confidence and motivation can be even harder to undo.

Why don’t we collect national data on reading and spelling skills earlier, in order to better understand learning in the vital early years? There’s been a lot in the media lately about the latest NAPLAN results, which show that a third of Australian kids are still struggling to read and write well. Indigenous, rural and low socioeconomic kids are struggling more than most. This is a serious social justice issue.

Reading and spelling problems start long before NAPLAN shines a light on them. Don’t the NAPLAN people know exactly what all children are expected to know and be able to do in Year 1, in order to measure it?

Well, maybe not. Our National Curriculum contains learning area and content descriptions, but not specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, timed (SMART) goals for phonemic awareness, word-level reading and spelling. The content descriptions for phonic and word knowledge for the first year of schooling are in the red text in the table below. I’m glad I don’t have to work out how to assess them! I’ve added the italics, and in the second column have put some of the kinds of goals for this skill area I’d want if I were teaching Foundation (which I’m not, so I’m sure they can be improved upon).

| National curriculum Foundation phonic and word knowledge content descriptions | Possible SMART Foundation phonic and word knowledge goals |

| Recognise and generate rhyming words, alliteration patterns, syllables and sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. (AC9EFLY09) Rhyme and alliteration are important in poetry, but in early literacy teaching, phonemes are what matter. Segment sentences into individual words; orally blend and segment single-syllable spoken words; isolate, blend and manipulate phonemes in single-syllable words (phonemic awareness). (AC9EFLY10) English one-syllable words can be up to seven phonemes long (e.g. ‘sprints’, ‘strengths’, ‘glimpsed’). Blending and segmenting even two or three sound words is very hard for many young children, and manipulation is even harder. How many sounds/what word structures (VC, CVC etc) are meant here? Recognise and name all upper and lower case letters (graphs) and know the most common sound that each letter represents. (AC9EFLY11) Vowel letter names are relevant sounds represented by these letters, so are useful when sounding out words. But when kids apply the same logic to consonant letters, they tend to write ‘car’ as ‘cr’, ‘left’ as ‘lft’, and ‘enemy’ as ‘nme’. Some research suggests letter name knowledge can interfere with children’s ability to apply the alphabetic principle. Kids must recognise letters, but is letter name knowledge essential in Foundation, especially for at-risk kids who are easily confused by too much information? ‘The most common sound each letter represents’ isn’t always what you might think. Fry’s 1966 large phoneme-grapheme count found 1801 instances of the letter Y as in ‘very’ (/ee/ sound), 211 of Y as in ‘my’ (/ie/ sound), 100 of Y as in ‘system’ (/i/ sound) and only 53 instances of Y as in ‘yard’. The letter O represented /oe/ as in ‘open’ 1876 times, /u/ as in ‘other’ 1723 times, and /o/ as in ‘not’ 1558 times in this count. Our National Curriculum needs to be more precise about sound-spelling relationships. Write consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words by representing sounds with the appropriate letters, and blend sounds associated with letters when reading CVC words. AC9EFLY12 If taught well, most Foundation kids can also learn to read and spell at least VC, CVCC and CCVC words like ‘in’, ‘at’, ‘help’ and ‘from’. Many can even spell /sh/, /ch/, /th/ and /ng/, though the National Curriculum doesn’t count these as consonants, which it defines as: “All letters of the alphabet that are not vowels. The 21 consonants are b, c, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, m, n, p, q, r, s, t, v, w, x, y, z”. Yet ‘vowel’ and ‘consonant’ are terms from linguistics for speech sounds, of which there are 44 in General Australian English. Use knowledge of letters and sounds to spell words. (AC9EFLY13) I guess it doesn’t hurt to state this while there are still kids out there being asked to memorise high-frequency word lists. But which letters, sounds and types of words? Read and write some high-frequency words, and other familiar words (AC9EFLY14) Which high-frequency words? How many? Three? Fifty? How many other familiar words? Understand that words are units of meaning and can be made of more than one meaningful part (AC9EFLY15) Which prefixes and suffixes should be taught in Foundation? Will teachers using lists like the Oxford Wordlist start teaching how words are built? The Oxford Wordlist includes ‘lot’ and ‘lots’, ‘cousin’ and ‘cousins’, ‘live’ and ‘lived’, ‘play’, ‘played’, ‘playing’ and ‘playground’, and ‘friend’, ‘friends’ and ‘friend’s’, as though they’re unrelated words. | Blend, segment, read and spell at least 90% of vowel-consonant (VC), CVC, CVCC and CCVC words containing the following sound-spelling relationships: Vowel sounds as in ‘at’, ‘red’, ‘him’, ‘on’, ‘up’, ‘put’. Consonant sounds as in ‘bib‘, ‘cat’, ‘did‘, ‘frog’, ‘got’, ‘him’, ‘jump’, ‘kit’, ‘leg’, ‘mum‘, ‘nest’, ‘pop‘, ‘run’, ‘sift’, ‘is‘, ‘ten’, ‘vet’, ‘win’, ‘yet’, ‘zip’, ‘shop’, ‘chin’, ‘thin’, ‘them’, ‘swing‘. Blend, segment, read and spell at least 60% of words with: CCVCC, CCCVC and CVCCC structures and the above sound-spelling relationships. Position-related consonant spellings as in ‘quit’, ‘box‘, ‘off’, ‘well‘, ‘mess‘, ‘buzz‘, ‘luck‘, catch, dodge, ‘when’, ‘bank’, ‘solve‘. Inflectional suffixes: regular plural (s, es), past tense (ed), third person (s, es), present progressive (ing), possessive (‘s, ‘), comparative (er), superlative (est), past participle (en). Derivational suffixes: agent noun (er), adjective (y), adverb (ly). Final syllable -le as in bottle. Contractions as in ‘isn’t‘, ‘can’t‘, ‘don’t, ‘it‘s‘. Read at least 60% of these not-yet-fully-decodable words in connected text: the, we, she, he, me, be, a, of, are, you, your, for, or, more, before, her, sister, over, under, after, were, to, do, who, two, room, zoo, too, soon, what, was, want, where, there, here, came, name, made, make, ate, I, like, time, side, so, go, no, home, hope, one, once, love, some, come, say, day, play, they, boy, toy, now, down, new, few, out, our, house, about, found, first, girl, car, park, look, good, book, could, should, would, saw, all, call, ball, my, by, try, very, only, family, happy, see, been, three, sleep, eat, real, said, because, school, friend. |

If you’re in Melbourne and your Year 1 or 2 child can’t do the things in the right-hand column above, you might like to bring them to one our school holiday groups.

It’s up to each state to interpret the National Curriculum, so they can add more clarity and specificity, I guess. Two states – NSW and SA – now test all Year 1 students’ phonics skills, and there is a free, online Australian Year 1 Phonics Check available for anyone to use, along with a phonics progression.

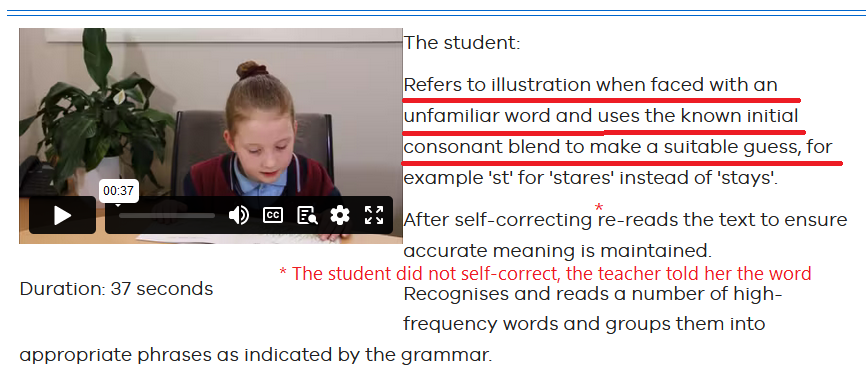

My own state, Victoria, has devised its own, watered-down version of the Year 1 Phonics Check (10 questions not 40). I agree with critics’ description of this: hopeless, and encourage Victorians to tell the current Parliamentary Inquiry into the state education system this, and whatever else you think needs saying, before 13th October. We’re supposed to be the Education State, but our Education department is still recommending the use of Running Records, and the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority website still promotes guessing words from pictures and first letters. The picture and black text annotation below is a screenshot from the VCAA website (the cranky red additions are mine).

Year 1 children’s word-level reading and spelling skills will probably only be assessed consistently across the country if this becomes part of NAPLAN. In the meantime, the growing number of teachers around the country who understand learning science (often thanks to grassroots groups like RSS, TFE or SBP) will keep setting high, SMART reading and spelling goals for young learners, teaching directly, explicitly and systematically, and checking their progress with more valid and reliable assessments than Running Records. I just wish they had more system-wide clarity and help.

Photo at top: https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-oyqyx

New word-building videos

0 RepliesI’ve made three very short videos (each under 90 seconds) showing how lots of long words are built by adding prefixes and suffixes to base words. The tiles depicted are from the Spelfabet Moveable Alphabet and Affixes, many of which flip over, making it easy to demonstrate juncture changes e.g. how ‘y’ changes to ‘i’ in ‘funny-funnier’, and final consonants double in ‘run-running’ and ‘hop-hopping’.

The aim is to minimise wordy explanation, and maximise demonstration, so I’ll stop explaining them now, and let them speak for themselves. Hope you like them.